It turns out that the shift along racial lines among evangelical and Reformed Protestants is remarkably recent. Some have objected to seeing 2014 as the turning point, but Jemar Tisby seems to provide the smoking gun:

remembering Brown on the five-year anniversary of his killing would be incomplete without acknowledging the impact that this tragedy had on race relations within American evangelicalism.

I know how that day and the subsequent events affected my faith and my relation to those who I once thought of as my spiritual family.

Six days after Brown’s killing, I wrote for the first time publicly about my traumatic encounters with the police.

Every black man I know has harrowing stories of being pulled over, searched, handcuffed or even held at gunpoint. When I encouraged readers to “pause to consider the level and extent of injustice that many blacks have experienced at the hands of law enforcement officers,” the responses disclosed a deep divide.

Tisby goes on to talk about the criticism that he and other African-American evangelicals for questioning police brutality. He then observes:

Black Christians like me and many others began a “quiet exodus” from white evangelical congregations and organizations. We distanced ourselves both relationally and ideologically from a brand of Christianity that

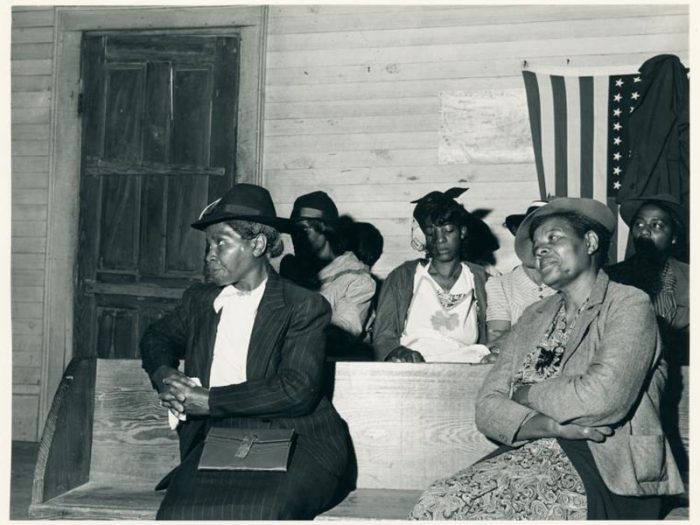

seemed to revel in whiteness.Now, after this quiet exodus, we find ourselves wandering in a sort of wilderness. Some are rediscovering the black church tradition and moving in that direction for healing and solidarity. Others, often by necessity, have remained in white evangelical spaces but with a new degree of caution. Some of us still don’t have a faith community to call home.

In sum:

Brown and Ferguson highlighted that when it comes to some parts of conservative evangelicalism, whiteness is not a bug, it’s a feature.

Who can judge another’s personal experience? I do not doubt that 2014 was traumatic for Tisby and many African-Americans, though I still don’t see the issue of police brutality as simply indicative of a black-white divide in the United States. In the hyphenated world in which all Christians live, it seems possible to support in general the functions of the police and oppose racism. In other words, opposition to racism should not be synonymous with hostility to law enforcement. I could well imagine, for instance, someone supporting Robert Mueller’s investigation (part of law enforcement) of the 2016 presidential election and detesting racism.

What is a problem, though, is to write a book with a tone of exasperation that white Christians just don’t get it. Not only does Tisby in his book fault white Christians for being tone deaf to race today. He adds that this is the way it has always been. The white church has been racist and always oblivious.

But if it took 2014 for an African-American Christian to see the problem, might not Tisby also have empathy for those who are five years late?

Meanwhile, to John Piper’s credit, his book on racism came out in 2011. He did not need cops in Ferguson, Missouri to see what Tisby saw three years later. Here is how Collin Hansen reviewed Piper’s book:

Tim Keller writes in his foreword that conservative evangelicals “seem to have become more indifferent to the sin of racism during my lifetime” (11). That would indeed be a major problem, since conservative evangelicals have been responsible for so much of the institutional racism of the last 60 or so years. Piper saw racism in the form of Southern segregation. The church of his youth voted in 1962 to ban blacks from attending services. His mother, however, opposed this motion. Piper’s experience explains the burden for writing this book, in which he argues, “Only Jesus can bring the bloodlines of race into the single bloodline of the cross and give us peace” (14). No political platform, lecture series, listening session, or economic program can cure what ails us. Nothing but the blood of Jesus can wash away our sin and make our diverse society whole again. Sadly, white Christians have so often perpetuated racism that we’ve largely lost the moral authority to help our neighbors confront and overcome this sin.

Bloodlines opens with a brief recap of racial history in the United States focused on the leadership of Martin Luther King Jr. and his masterful writing, particularly “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” This historical jaunt may indicate Piper anticipates a youthful readership who did not live through these events. Or maybe he believes the race problem is worse than ever. He writes, “There are probably more vicious white supremacists in America today than there were in 1968” (27).

Either way, no one can argue the church has made sufficient progress on race. Sunday mornings remain largely self-segregated. But Piper sells himself short as a credible leader when it comes to racial reconciliation. He and his church have made commendable and costly investments to live out what they profess about the gospel that unites Jews and Gentiles. I would have gladly read much more than a few appendix pages on Bethlehem’s experience of trial and error. We need theology that exalts the work of Jesus, and we also need examples from churches that have enjoyed God’s gracious favor in the form of racial diversity and harmony.

With Keller and Piper alert to the problem of racism in white Protestant circles in 2011, Tisby’s dating of the racial rift is curious. It is hard to believe he was not reading Keller and Piper.