Machen may have been ahead of his time, even before Barth and Brunner:

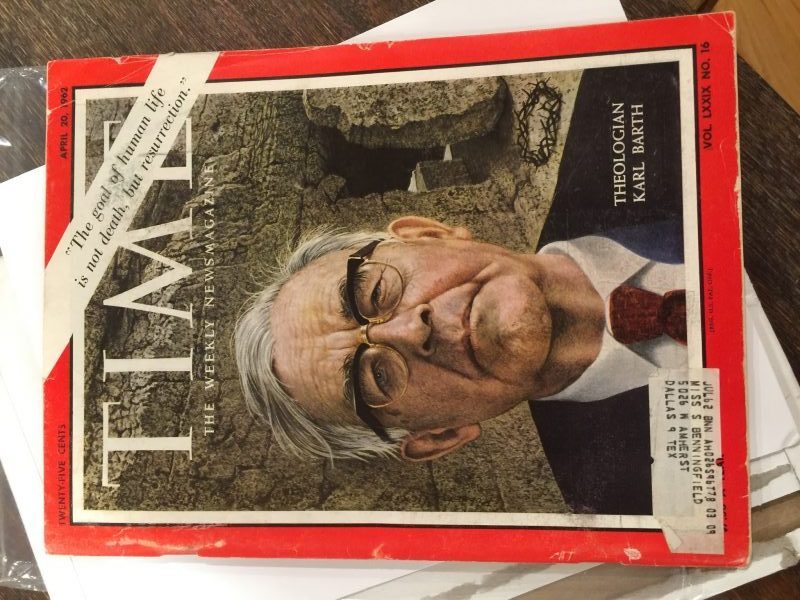

Half a century ago it seemed to many that the Protestant theological movement usually designated as “modernism” or “liberalism” was finally being overcome and that the only liberals remaining were relics of nineteenth or early twentieth century thought. Of course, many lay persons who had been nurtured on modernism by their pastors and Sunday School curricula had not been exposed to serious critiques of liberalism by younger or more theologically enlightened pastors. Nevertheless, it seemed that the tide had turned. Despite their differences, continental European theologians like Karl Barth and Emil Brunner were giant slayers of liberalism, and it seemed that no one with a sound knowledge of biblical theology and Christian doctrine would take seriously the nostrums of liberalism. Nor did this mean the triumph of fundamentalism, a reaction to liberalism which had begun in the United States of America. The errors of both liberalism and fundamentalism were exposed, and serious Christians were engaged in a recovery of the apostolic and catholic faith albeit according to their own heritage—Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, Methodist, etc.

Today it seems that many so-called mainline Protestants somehow missed the overcoming of liberalism. They consider themselves to be “progressives,” and while their terminology, themes, and concerns are not exactly the same as those of liberals a hundred years ago, progressives are direct descendants of liberals. Their self-chosen moniker of “progressive” indicates a belief in an ideology of “progress” (a predestined future of human aims by human means), which is descended from liberalism. Because of the chastening of liberal thought by the Neo-Reformation theologians like Barth, perhaps many progressives are anxious to profess their allegiance to the authority of scripture and doctrines of the church, but their profession of orthodoxy is belied by key interpretations which convert the meaning of scripture and doctrine which have been characteristic of Christianity from the beginning.

Because of a potential similarity between liberalism and progressivism, it is worthwhile to revisit some of the critiques of liberalism. One of the most famous was Christianity & Liberalism by J. Gresham Machen (1881-1937) published by Macmillan Company in 1923 when Gresham was a New Testament scholar at Princeton University. While Machen was a sophisticated scholar who published many books and articles for peer review, this book was written for the general reader. It was intended to be a manifesto against the dangers of liberalism in order to persuade clergy and laity to defend historic Christianity.

While this book is still well-known in Reformed evangelical circles, it has been largely overlooked by Protestants in mainline Protestant churches. Because Machen was a ecclesiastical activist who was an ally of fundamentalists in the battle against liberals, many Protestants assume that Machen himself was a fundamentalist. He was a conservative Reformed scholar who adhered to the theological school of thought known as the “Princeton theology,” but he was no fundamentalist. The “Princeton theology” is represented by the systematic theology of Charles Hodge and his son and the views of Benjamin Warfield who adhered to the teaching of John Calvin and who advocated for a doctrine of the ‘plenary inspiration” of the scriptures. Machen was critical of most of the features of fundamentalism, such as its millennialism and its advocacy of a few selected ideas they regarded as “fundamentals” rather than a robust adherence to the full Christian creed. While Machen adhered to a particular Reformed version of the faith, in this book he primarily defends the apostolic and catholic faith—or what C.S. Lewis would call “mere Christianity”—against liberalism. It is instructive that he book is titled Christianity & Liberalism, not “Fundamentalism & Liberalism.”

Perhaps one reason that this book has caused offense to mainline Protestants, who think of themselves as broad-minded, is because Machen contends that Christianity and liberalism are two different faiths. Some of the theologians who were roughly contemporary with Machen also strongly attacked the errors of theological liberalism, but they did not say bluntly that liberalism is contrary to Christianity. In 1907, the Scottish Reformed theologian P. T. Forsyth, in Positive Preaching and the Modern Mind, viewed liberal theology, “the theology that begins with some rational canon of life or nature to which Christianity has to be cut down or enlarged,” as a kind of theology which “works against the preaching of the Gospel.” In 1936, Karl Barth, in Church Dogmatics, I.1, The Doctrine of the Word of God, e.g. pp. 30-36, declares that “modernism” (or what he came to denote as “Neo-Protestantism”) is a “heresy” which is based on a false foundation but which still has the “form” of Christianity. Machen drew a harder line against liberalism as being in a different category altogether from Christianity. In the first sentence of his book Machen acknowledges that he takes the approach of making a sharp distinction between Christianity and liberalism so that the reader may be aided in deciding for himself between the claims of historic Christianity and liberalism. In all great contests of thought, there is always room for contestants to draw the lines as sharply as possible. After all, the most famous American liberal preacher, Harry Emerson Fosdick, had already taken the same approach in his polemical speech, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”…

Correcting liberalism takes more than Barthianism.

The thesis of Christianity and Liberalism, which is that Christianity and liberalism are in fact two different faiths, was revelatory to me when I was first exposed to Machen’s work three years ago as a new Christian and up to that point lifelong Roman Catholic. It has continued to leave a deep impression on me and is a work I need to revisit now that I am three years farther along. Sadly, however, at the time that I read his work, there seemed to be no one else in either OPC I visited who had also read this work and with whom I could discuss it; we do not live in a reading age. One woman was a more fervent reader of “Christian romances” than any books of substance. As always, I deeply appreciate these thought-provoking posts; I certainly never engaged in such intelligent or thoughtful conversation with anyone at either OPC I visited.

LikeLike

“Ecclesiastical activist” is my new favorite moniker. Let no one say that Machen wasn’t an activist.

LikeLike

The fundamentalists certainly claim Machen. If you read Sidwell’s “The Dividing Line”, which is a history and theology of the doctrine of separation as understood by the fundamentalists, you’ll find him mentioned among their own.

LikeLike

Nate, how about ecclesiastical terrorist?

LikeLike