Some bloggers claim to give you historical perspective, and others (like mmmmmmeeeeeEEEEE) simply cut and paste:

In the 19th century, presidents had little involvement in crisis response and disaster management, for both technological and constitutional reasons. Their influence was limited technologically because the country lacked the communications capabilities needed to notify the president in a timely manner when disaster struck hundreds of miles away. Even when the telegraph and later the telephone entered the equation, the nation still lacked the mass media needed to provide the American people with real-time awareness of far-flung events. Naturally, this affected the political call for presidents to involve themselves in local crises.

Then there were the constitutional reasons. In the 19th century, there was a bipartisan consensus that responding to domestic disasters was simply not a responsibility of the commander in chief. In the late 1800s, both Democrat Grover Cleveland and Republican Benjamin Harrison made clear that they did not see local disaster response as a federal responsibility. Cleveland vetoed funding appropriated by Congress to relieve drought-stricken Texas farmers in 1887 for this reason. And Harrison told the victims of the Johnstown flood in 1889 that responding to the disaster, which killed more than 2,000 people, was the governor’s responsibility.

That may be the federal government equivalent of the spirituality of the church: POTUS has limited means for specific ends.

But what about the twentieth-century presidency?

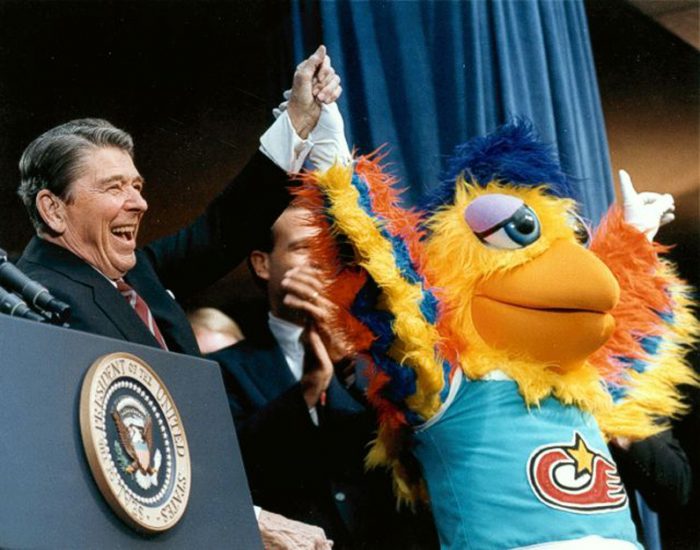

The Austin shooting would remain the deadliest in the nation’s history for 18 years. (In order to abide by a standard definition of “mass shooting,” the following addresses those events identified by the Los Angeles Times in a compilation of mass shootings in the U.S. since 1984.) In July 1984, during Ronald Reagan’s first term as president, a gunman killed 21 people at a McDonald’s in San Ysidro, California. Unlike Johnson, Reagan did not say anything publicly about the shooting. In fact, a search by the New York Times revealed that “[t]he Times did not report any comment from the administration of President Ronald Reagan. His public papers show no statements on the subject in the days following.” McDonald’s suspended its own commercials following the incident, and in this there appears to be some indication of Reagan’s approach to these kinds of matters. When the Tylenol poisonings took place in Chicago in 1982, Reagan had also stood back, letting Johnson & Johnson take the lead in the response. Reagan appears to have been of the view that local tragedies should be handled at the local level, deferring to private-sector entities, when appropriate, to handle problems.

Reagan also appears to have remained quiet after the other two mass shootings during his presidency, one in Oklahoma and one in California. The 1986 Edmond, Oklahoma, shooting appears to be the first one in which a disgruntled post-office employee was the killer, the start of an unfortunate trend of about half a dozen of these shootings that would inspire the phrase “going postal.” Similarly, Reagan’s successor and former vice president, George H. W. Bush, also generally avoided making statements about the four mass shootings during his administration. A January 1989 shooting at an elementary school in Stockton, California, which took place in the last days of Reagan’s tenure, did contribute to a decision early in the Bush administration to issue a ban on the importation of what the New York Times described as “semiautomatic assault rifles.”

Then Bill Clinton turned POTUS into the griever-in-chief:

On a clear spring day, two Colorado high-school students set out to methodically shoot classmates, murdering 13 and then killing themselves. This event was too big and too horrific for a radio address or a brief visit with some of the survivors in another city. Instead, Clinton went to Colorado the next month, just before the Columbine commencement. While there, he gave what appears to be the first major presidential address in reaction to a mass-shooting event. In front of 2,000 people, and joined by First Lady Hillary Clinton, the president told the moving story of a talented young African-American man from his hometown in Arkansas who had died too young. At the funeral, the young man’s father had said, “His mother and I do not understand this, but we believe in a God too kind ever to be cruel, too wise ever to do wrong, so we know we will come to understand it by and by.”

During the speech, Clinton made a number of noteworthy points. First, he recognized that these kinds of shootings were becoming a recurring phenomenon: “Your tragedy, though it is unique in its magnitude, is, as you know so well, not an isolated event.” He also noted that tragedy potentially brings opportunity, saying, “We know somehow that what happened to you has pierced the soul of America. And it gives you a chance to be heard in a way no one else can be heard.” At the same time, Clinton warned of the dangers of hatred: “These dark forces that take over people and make them murder are the extreme manifestation of fear and rage with which every human being has to do combat.” Finally, he expanded on his violence/values dichotomy, exhorting the crowd to “give us a culture of values instead of a culture of violence.” Clinton closed with the story of jailed South African dissident Nelson Mandela, who managed to overcome hatred and become the leader of his country.

All in all, it was a vintage Clinton performance — feeling the pain of the audience, highlighting the importance of values, and trying to bring the nation together in a shared enterprise.

What about Barack Obama and Donald Trump? So far, both have set records:

It is far too soon to know if the Trump administration will surpass the Obama administration’s tragic record of 24 mass shootings in two terms, but Trump’s presidency has already witnessed the worst mass shooting in American history. On October 1, 2017, a 64-year-old man — quite old compared to the profiles of other mass shooters — killed 58 people before killing himself at a country-music festival in Las Vegas.

For the record, the number of mass shootings under the previous presidents runs like this:

Johnson 1

Reagan 3

Bush (I) 4

Clinton 8

Bush (II) 8

Obama 24

That looks like a trend but seemingly 2017 changed everything.

In other words, if politicians were a bit more circumspect about the attention they shine on certain problems, perhaps we would have fewer of them.

LikeLike