That feeling when scholarship nurtures devotion. The relation of Paul to Christ is a relation of love; and love exists only between persons. It is not a group of ideas that is to be explained,… More

Why You Don’t Need the Westminster Confession (or Calvin or Winthrop) to do Protestant Politics?

One of the tendencies in the critics of Kevin DeYoung’s defense of John Witherspoon and the American revision of the Westminster Confession (not mentioned here) is a need to base contemporary political reflection and action – even – on past Protestant models. The critics of DeYoung did this by reference to the meaning of the Westminster Confession. Others at American Reformer have also argued for a recovery of early modern Protestant politics. The advantage of this argument is that it paints Witherspoon, American Presbyterians, and always 2k advocates in the corner of departing from Reformed orthodoxy.

But what if you don’t need pre-Lockean understandings of politics and the good society to have a Protestant voice in liberal political structures? What if today’s Protestants who want to advocate for Christian norms looked to Presbyterians who both accepted the terms of liberal democracy and free markets and advocated Protestant-friendly positions on matters of political debate? What if you could be a kind of Christian nationalist without needing to read all of the pre- or early-modern Protestant theologians on the divine mandate for the Christian magistrate and a godly commonwealth?

That is what happened in the 19th century in England, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, and the United States. Presbyterianism began in 16th century England and Scotland as a force of opposition to rule by bishops and continued as a form of checks upon elites in both government and the church, Presbyterians saw overcoming injustices of the past with improvements that led to a fairer future. Such a disposition almost always places Presbyterians on the side of freedom and limited government whether in the form of freedom of conscience or ecclesiastical autonomy from meddling magistrates. This cast of mind nurtured in Presbyterians at least sympathy if not outright support for political and economic reforms that reduced the authority and wealth of the few and expanded society’s benefits as broadly as possible. Such an outlook, as in the case of the United States, could lend support for small government and reliance on voluntary associations for improving social conditions. But even where the state’s footprint in managing the forces of modernization was larger than the American form of government, Presbyterians generally supported those “good” governments whose rule extended the blessings of modern society as widely as possible.

For this reason, increase in suffrage, more extensive representation in government, free trade and better distribution of goods for more affordable prices, higher rates of literacy and advanced learning, and greater suppression of vices, not to mention the separation of church and state were all policies on Presbyterians’ horizon on the phase of their particular nation’s evolution.

Among the proponents of these views were Charles Hodge in the United States, William McKerrow in England, Thomas Chalmers in Scotland, Henry Cooke in Ireland, George Monro Grant in Canada, and James McCosh – can you believe it – in Scotland, Ireland, and the United States. These Presbyterians may have been on different places on the page of Reformed theology and Presbyterian worship, but their outlook on government and society stemmed from their understanding of Presbyterianism in its modern, liberal, political version. Advocates of the spirituality of the church or its 2k nomenclature may take issue with these Presbyterians, but they show you don’t need to turn the clock back before 1789 to have Presbyterian politics.

It goes without saying that the constellation of political and economic positions adopted by these Presbyterians was a long way from the godly commonwealth of the Scottish Reformation or England’s Second Reformation. But after the Glorious Revolution (1689), Presbyterians learned by experience and reflection that the same political arrangements that lightened the church’s burden from an overreaching magistrate were also among the tools by which modern nations could fashion a generically Christian society.

Rev Kev vs. The American Reformers (who POUNCED!!)

Kevin DeYoung deserves praise for defending John Witherspoon and the American revisions to the Westminster Standards. Some of us were doing this back in the day when the Federal Vision was echoing the theonomists. But the post-liberal turn among Protestant Christian nationalists and Roman Catholic integralists has increased the need for a defense of the American revisions and their harmonization of Reformed teaching and the American Founding (republicanism, constitutional federalism, religious liberty).

The post-liberal Protestants at American Reformer have not welcomed DeYoung’s understanding of American Presbyterians’ revisions of Westminster. Some argue for continuity between the original Westminster Confession and the 1789 revision. Others go farther and assert that even the American Revisions require an affirmation of a religious establishment.

What is largely missing from the critics of DeYoung is attention to the Covenanters (or Reformed Presbyterians) whose views are similar to theirs — the American Founding is seriously flawed — and whose understanding of the civil magistrate was the dominant view among Presbyterians at the time of the Westminster Assembly. DeYoung’s first article does in fact address the corner into which the Covenanters had painted Presbyterians. He wrote:

In 1707, the Act of Union brought together England and Scotland under the name of Great Britain. Many Presbyterians opposed the union as inconsistent with the principles celebrated in the National Covenant (1638) and the Solemn League and Covenant (1643) and as undermining the Revolution Settlement (1690) which restored Presbyterian government to the Established Church in Scotland.

DeYoung later adds the change in Presbyterianism that transpired after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He uses John Coffey, the leading scholar of Samuel Rutherford, to describe that change:

“With the exception of the Reformed Presbyterian Covenanters and some Seceders, eighteenth-century Presbyterians found ways of distancing themselves from the Westminster Assembly’s teaching on the coercive powers of the godly magistrate in matters of religion…. In every part of the English-speaking world, Lockean ideas of religious liberty looked increasingly attractive to Presbyterians who feared Anglican hegemony or saw little prospect of becoming the dominant majority.”

Zachary Garris says the Covenanters are not in the mainstream — that’s true for America today. But it was not true for the people who wrote the Westminster Confession — Presbyterians, Puritans, and Independents from England and Scotland. In fact, Scotland’s covenants with her kings (the Stuarts) who became the kings of England as well set the standard for political theology at the Westminster Assembly. Here’s why:

The Scottish Reformation gained a victory in 1581 with King’s Confession of 1581 by which James VI (later James I of England) vowed, with Parliament, the Kirk, and the people to uphold and defend the true religion (Reformed) and oppose the false religion (Roman Catholicism).

In 1638, this time with Charles I (James’ son) imposing the Book of Common Prayer on the Scottish Kirk, Parliament, the Kirk, and the people ratified the National Covenant. The expectation was for Charles to pledge his allegiance to this covenant because of the original (King’s) covenant with his father.

Soon after the National Covenant, Scottish military went to war with Charles — you guessed it, he didn’t take the vow — in the first of two “Bishop’s Wars” (1639-1640). The Scots’ covenants and war with Charles were the trial run for the English Parliament’s civil war with the king (1642-1649), the same Parliament that called for an overhaul of the Church of England and gave the responsibility to the Westminster Assembly. The English Parliament needed military help from the Scots who in turn gave it conditioned on Parliament’s ratifying an international covenant — the Solemn League and Covenant (1643). Although that covenant had different legal justification from the Scots’ National Covenant, the Solemn League and Covenant extended to England and Wales the same cooperation among the civil government, the church, and the people to uphold the true faith (and oppose the false religion of Rome) in Scotland.

Covenanting and national covenants were hardly peripheral to seventeenth-century Presbyterianism of the Westminster Confession. Covenanting likely explains one of the oddest chapters in the Confession of Faith — chapter 22 on Oaths and Vows. (If you are in a covenanting mind set, you may likely clarify the theological import of promises taken in the civil and ecclesiastical realms.)

If you wonder where Christian Nationalism among Presbyterians comes from, you may well want to look to the Covenanters.

This covenanting backdrop is especially important for understanding the American revision of the Westminster Confession. By the 1780s, the covenanting position was not part of the Presbyterians who comprised the first General Assembly of the PCUSA. That is because the Covenanters had formed their own communion, the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America. Which is also to say that everyone in the Presbyterian world (England, Scotland, Ireland, the United States, and eventually Canada) gave up on covenants with Scottish monarchs. The lone exceptions were the Covenanters and certain sectors of the Seceders (Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church).

Why the critics of Dr. DeYoung do not resonate with or follow the Covenanters is a mystery. So is their unwillingness to acknowledge that they desire a relationship between the church and civil magistrate like the ones the Covenanters briefly had between 1638 and 1650. There is also a good chance that the American Reformers who pounced on Dr. DeYoung agree with Covenanter assessments of the American Founding. This is the Covenanter understanding of the U.S. Constitution (which puts a dent in American patriotism):

There are moral evils essential to the constitution of the United States, which render it necessary to refuse allegiance to the whole system. In this remarkable instrument, there is contained no acknowledgment of the being or authority of God —there is no acknowledgment of the Christian religion, or professed submission to the kingdom of Messiah. It gives support to the enemies of the Redeemer, and admits to its honours and emoluments Jews, Mahometans, deists, and atheists—It establishes that system of robbery, by which men are held in slavery, despoiled of liberty, and property, and protection. It violates the principles of representation, by bestowing upon the domesticity rant who holds hundreds of his fellow creatures in bondage, an influence in making laws for freemen proportioned to the number of his own slaves. This constitution is, notwithstanding its numerous excellencies, in many instances inconsistent, oppressive, and impious.

Since the adoption of the constitution in the year 1789, the members of the Reformed Presbyterian Church have maintained a constant Testimony against these evils. They have refused to serve in any office which implies an approbation of the constitution, or which is placed under the direction of an immoral law. They have abstained from giving their votes at elections for legislators or officers who must be qualified to act by an oath of allegiance to this immoral system. They could not themselves consistently swear allegiance to that government, in the constitution of which there is contained so much immorality. (Reformation Principles Exhibited, 1807)

The differences between the PCUSA and the RPCNA reflect the changes that occurred throughout the Presbyterian world once most communions abandoned Scotland’s National Covenants. Locke made a lot more sense of British society for accommodating religious diversity than insisting on promises Stuart monarchs had made to Scotland and England. And that difference was an important factor in Witherspoon’s role in revising the Westminster Confession and Catechisms.

Dr. RevKev understands that both the moderates and the evangelicals in the Church of Scotland, as well as the Old Side and New Side Presbyterians in America had no sympathy for Scotland’s covenants. They had move on.

Critics of Dr. RevKev may refuse to be lumped with the Covenanters. That’s fine. But they do need to take the Scottish background into account both to understand the context for the Westminster Assembly and the reasons behind American Presbyterians revising the Confession of Faith.

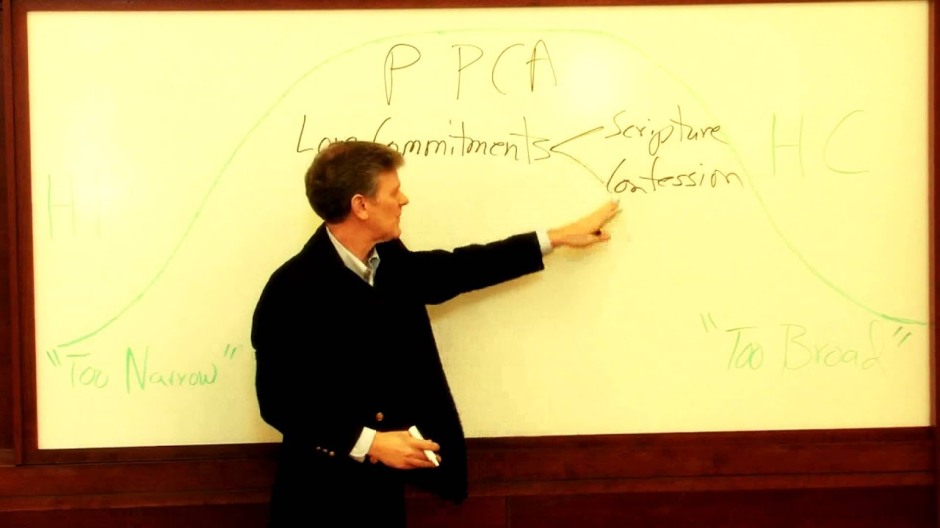

The PCA Back in the Day: This Time for Real

This is the last of a retrospective inspired by the current assembling of the PCA General Assembly. What follows is the fourth assessment of the PCA’s 2010 Strategic Plan. It is by Martin Hedman, who was then the pastor of Mission Presbyterian Church in La Hambra, California. The entire series was published in the Spring 2010 issue of the Nicotine Theological Journal.

Sufficiency of Scripture for PCA Planning

Several years ago a young man came before our presbytery to be licensed to preach. As is our practice, the Candidates and Credentials committee led the initial questioning, asking a subset of the questions he had prepared as part of his written examination. The young man was poised and confident in his answers. Clearly he had prepared, knew his material and answers well. The committee asked this man to define justification. His answer? “Justification is an act of God’s free grace, wherein he pardons all our sins, and accepts us as righteous in His sight, only for the righteousness of Christ imputed to us, and received by faith alone.”

Beautiful answer! Right out of the Shorter Catechism. Unlike many men who try to memorize the catechism and recite its answers during a floor exam, he did not hesitate or stutter in any way. Many of his answers were just like this one, well spoken and directly from the catechism.

After asking a number of selected questions out of the written exam, the committee opened up the questioning to the floor of presbytery. As usual, a number of questions concerned matters of clarification, some to flesh out answers or reasoning, and some to explore additional territory. At one point – I don’t remember who it was but do recall it was one of the older men – a presbyter commended the young candidate on his ready answers and his felicity in using the catechism. The presbyter then asked a question something like this: “You clearly know what the doctrine of justification is. Can you tell us what it means for you in your daily life as a Christian?”

“Whoa!” I thought to myself. “Is this a veiled attack? Is it wrong for a guy to know his catechism? Was this a some squishy-soft, feel-good, pietistic jab?”

And then I watched as the young candidate really, genuinely struggled with his answer. The poise and confidence were gone as he searched an answer. What he said I don’t recall but it wasn’t very satisfying. I don’t even recall if there was a follow up by the questioner. What did stay with me was the thought that this shouldn’t be so hard to answer.

Having learned about them from the guy (i.e. R. Scott Clark) who came up with the acronyms, I am in no way interested in either QIRC (Quest for Illegitimate Religious Certainty) or QIRE (Quest for Illegitimate Religious Experience). At the same time, the Reformed faith acknowledges the necessary link between doctrine and practice. They are inseparable.

Nevertheless, too often we seem to have trouble connecting them. It may be the young theologian on the floor of presbytery who hasn’t thought through the implications of the doctrine of justification – doctrine leading to practice. Or it may be the denominational committee that wants to be strategic and forward thinking but hasn’t thought through the biblical foundations – practice without foundation in doctrine. The latter is the case with the recently proposed and passed SP for the PCA. Both problems flow from a lack of appreciation for the sufficiency of Scripture. This is especially evident in the SP.

To illustrate let me take one example from the plan itself. The original draft of the SP called for “safe places” in which to discuss controversial theological matters, or in some cases give men the opportunity to express new ideas without having to worry about being brought up on charges. Prior to actual presentation to GA the wording was changed to “civil conversation.”

First, this presupposes a problem within the PCA’s current theological environment which I do not grant but will set aside for the sake of brevity. Second and more important, the plan proposes a solution that seems completely ignorant of Scripture. Granting that there are times and places where elders, deacons and others do not hold civil conversations, and even that those occasions are far more prevalent than we ought to be comfortable with, what is the solution?

The SP proposes places to enter into civil conversations, by means of public forums at General Assembly, similar forums at presbyteries, and the gathering together of those who disagree to discuss how to get along with each other. Will this work? I have no idea. No. Wait. Actually, I do. The supposition of “uncivil” conversations also presupposes that people are getting together, in some fashion, for uncivil purposes. So, we are going to establish more places to have more conversations? And that will somehow magically make them civil? Who comes up with this sort of sociological claptrap?

Answer: those who don’t look to Scripture, in other words, those who by their proposals and actions demonstrate that they don’t take the sufficiency of Scripture seriously. Sure, maybe they do for doctrinal purposes. After all, that’s what 2 Tim 3:16 says: “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness.” Isn’t this the “go-to” verse to show that we don’t need Tradition (a la the Roman Catholics), that we are right to proclaim our belief in sola scriptura?

Of course it is. But there’s more. The last clause says that Scripture is also profitable – sufficient – for training in righteousness. And verse 17 explains why: “that the man of God may be competent, equipped for every good work.”

So, if we want men to hold civil conversations, an example of righteous living and certainly a biblically sound good work, shouldn’t we look to Scripture for how and why men should do so? Of course we should. But we don’t make that connection nearly as often as we should. We want to be wise. We want to take action, be responsible, and see results. We want something to happen as a consequence of our having done something. We are, sadly, manifestly unsatisfied with the preached and taught Word of God and the Spirit’s promised ability to make it go out and not return void. In this, we show a lack of belief in Scripture.

Do we want civil conversations? Then we need something better, something more grounded and solid than clever schemes. We need God’s Word. We need his Spirit to change hearts, convict men of sin, and produce the fruit of repentance, so that we might walk in a manner worthy of the Spirit’s effectual calling.

Here is just one, all too short, example of what we need to be saying to each other, admonishing and exhorting one another with, if we really desire godly exchanges of opinions and ideas in the PCA:

Ephesians 4:11-25 tells us, among other things, that we have proclaimers and teachers of God’s Word to help us grow up in the fullness of Christ, that we are to speak the truth in love, so that we might grow up in every way into Christ, and that we speak the truth with our neighbor because we are members of one another. We have God’s Word, we are in Christ and we are to grow up in Christ, we are united in Christ – if all these are true then how can we not be of a mind to speak truth to each other in love? If we don’t, how can we claim, how can we hope, to grow into the fullness of Christ? Far better than meetings and forums is a solid grasp of who we are in Christ and all the implications that flow from that blessed reality.

Now there’s a strategy! We believe and confess that God’s Word works effectively for the building up of God’s people in righteous and holy living. We need to put that belief into practice!

God’s Word really is sufficient – for doctrine, and yes for training and competence in righteous living, including civil conversations with our brothers and sisters in Christ.

The Return of The PCA Back in the Day

This is the third in a series of pieces – inspired by the PCA General Assembly assembling in Chattanooga – that appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of the Nicotine Theological Journal in light of the PCA’s approval of its Strategic Plan. This one comes from Wes White, who was then pastor at New Covenant Presbyterian Church in Spearfish, South Dakota.

Why I Voted “No”

How can you be against “civil conversations,” “more participation in General Assembly,” and “God’s global mission”? Many people have asked this question about the opponents of the PCA’s so-called SP. I believe that there are two ways in which we can view the PCA’s SP, either in the abstract, simply in terms of what the words say, or in the concrete in terms of what those who put the plan together actually want to accomplish. I think the latter way of viewing it is the more appropriate one, but, in either case, I would have voted “no” on every single point.

In the abstract, the SP may seem quite harmless. The problem is that we need to begin by asking, why do we need a strategic plan at all? What are we trying to accomplish? What the PCA calls “strategic planning” has been going on for a while. In the year 2000, the nine Coordinators of the Committees and Agencies of the PCA thought we needed a plan for the future. The result was a 24-person Strategic Planning Steering Committee. They reported at the 2003 GA with a booklet entitled Being Revived + Bringing Reformation. This report outlined the mission, vision, and strategic priorities of the committee.

The second phase of strategic planning began in 2004 with the re-constitution of the SP committee. Its task was three-fold: engaging ruling elders, preparing the next generation, and organizing resources to better serve our corporate mission. The re-constituted committee proposed to changes to church life. The first was the restructuring of General Assembly to limit parliamentary options on the floor of General Assembly and place a much greater emphasis on the committees of commissioners and especially the overtures committee. The second was the creation of the Cooperative Ministries Committee (CMC), a body where the various committees and agencies of the PCA could communicate with one another and “facilitate” further strategic planning. Both of these items were proposed at the 2005 General Assembly and passed at the 2006 General Assembly.

While I do believe that the changes to the PCA’s Rules of Assembly Operation (RAO) have been helpful, one thing is rather obvious. Little progress has been made on the major goals set forth by the 2004 committee. The proportion of Ruling to Teaching Elders is about the same as it was in 2006. The next generation is doing roughly the same thing as it was in 2006. Missions aren’t that much different either.

What have we really accomplished in these areas? Not much, it seems to me. What makes us think that this will be any different? We may feel good about passing these things, but I don’t see any evidence that it will make any difference.

One problem is that little to no research has assessed the perceived problems. In his talk to the Administrative Committee (AC), TE Bryan Chappell, president of Covenant Seminary and author of the informational part of the plan, noted that the number of candidates to the ministry had dropped from 599 in 2004 to 298 in 2008. I asked him in committee if anyone had conducted research to assess this drop. His answer was “no,” and, in his opinion, he didn’t think you could do research on who was not there, but he did suggested that the lack of civil conversations was responsible. This is precisely the problem. Until we figure out why these figures are the way they are, I do not know how good a plan can be. (By the way, in 2009, the numbers were back up to around 550 candidates for ministry. What happened? That would be a good study for strategic planners.)

In sum, I opposed this plan in the abstract because it will not accomplish anything. But two additional problems are worth mentioning.

First, the SP came to the floor in a way that was contrary to the RAO. The CMC cannot present anything directly to the General Assembly. According to 7.3.c. of the RAO, strategic planning must include matters that normally come under the work of our other committees and agencies. Any action must be presented through the “appropriate” committee, which clearly means the committee or agency that normally presents such matters to the Assembly. Instead, the CMC presented it all through the AC, even though the matters in the plan related to Covenant College and Seminary, Mission to North America, and other committees. This point was part of a protest against the Assembly’s action in passing the SP.

Second, the AC included a funding plan that basically involves of tax on congregations. They must pay and if they do not for one year, they will owe back taxes plus the current year’s assessment. They will also lose their vote at GA until the local church and all their pastors pay what they owe to AC. This funding scheme is being proposed through an amendment to Book of Church Order 14-1. The problem is that the amendment says that General Assembly may “require” contributions for the support of General Assembly; whereas, BCO 25:8 states, “The superior courts of the Church may receive monies or properties from a local church only by free and voluntary action of the latter.” The Amendment is contrary to other parts of the Constitution and should have been ruled out of order.

In the concrete, the trouble with the SP is that revisions to language at the Assembly may not actually change what the planners originally intended. I am not confident that CMC and AC have corrected for the errors of their first proposal.

For example, the first theme of the SP was “safe places.” They changed the wording to “civil conversations,” but does that really change what the authors intended when they wrote “safe places”? Moreover, in these safe places (and this is in the latest version of the SP), it says that one way that it will be safe is that there will be “nothing chargeable in this context.” This is clearly contrary to the discipline of the church.

Another example is the idea that our missions would focus on “Gospel eco-systems.” This is a term apparently invented by Tim Keller to describe his model for planting churches in “city centers.” According to the SP, this means not only planting PCA churches but that we will fund research on “how to multiply them beyond the PCA.” I believe that our goal should simply be to plant churches. We should do this wherever God leads us and not set a priority as to where we are to work. However, according to Tim Keller, “If you have an…effective, contextualized way of communicating the gospel and embodying the gospel for center city residents, you’re actually going to win large numbers of them, it’s just going to happen.” Thus, it should be the PCA’s priority to multiply Gospel eco-systems, since they are certain to work. The logic behind this model contradicts the sovereignty of the Holy Spirit.

It is interesting to note that one of the persons who spoke in favor of “God’s Global Mission” was a missionary to the Indians in northern Alberta, Canada. He argued passionately for the “global mission” part of the plan, and I appreciated much of what he said. However, he should realize that “Gospel eco-systems” was changed to “centers of influence.” Does he think that Atlanta will view northern Alberta as a “center of influence”?

So, of course, I am for God’s global mission but do not believe in Gospel eco-systems. I’m not interested in establishing “centers of influence.” I am interested in personal evangelism and church planting. I did not see that as an emphasis in this plan, and thus I voted against this whole section because it was clear to me that our “leaders” were leading us in a different direction.

Why did I vote against the SP? I voted against it because the SP lacks real strategy, because it was passed in a way that was contrary to our BCO and RAO, and because I do not agree with the priorities of those who put this plan together and who will be in charge of its implementation.

Son of The PCA Back in the Day

While American Presbyterians think more about Chattanooga than Tehran — thanks to the PCA General Assembly — here is the second installment from contributors to the Spring 2010 issue of the Nicotine Theological Journal on the denomination’s 2010 Strategic Plan.

This one comes from Lane Keister, who was then a PCA pastor serving in CRC and RCA congregations in North Dakota.

No doubt many in the upper echelons of the PCA were quite disturbed to find resistance to the ideas of the Strategic Plan (hereafter SP). After all, this was a plan designed to unify the denomination, and very little unification has happened as a result of this plan. Most of the action points of the plan passed with very significant minority opposition. Furthermore, the reasons for the majority vote were not always admirable. There were a fair number of people voting just in order to show confidence in the leadership, or because they liked certain people championing the cause of the plan. Many had not even read the plan. This tends to remind me of the way in which the government health care package was passed. In my opinion, this is a terrible way to do the business of the church. If people are going to go to General Assembly, they are responsible for knowing what is on the docket, and being prepared for the arguments, such that real debate can happen.

I was speaking with my brother-in-law, an OPC minister, and he mentioned that he had watched a good deal of the debate on the floor, and was frankly shocked at how little actual debate transpired. He immediately asked when we were going to arrive at our senses, and proceed to a delegated assembly (like the OPC). This point is profoundly relevant, since a great deal of the expenses that the Administrative Committee incurs have to do with the General Assembly, and one of the most controversial aspects of the SP was the funding proposal. There are too many delegates to have the GA at any regular church of the PCA, even our largest. The expense of renting a convention center in a major city is astronomical. Furthermore, the debates cannot be tight and to the point with so many delegates at the assembly. My brother-in-law added that the “debate” was little more than political posturing, with very little in the way of biblical, confessional, or church polity argumentation. This has been true of the PCA’s GA for many years now. Someone needs to propose a delegated model. The Administrative Committee no doubt needs to be funded (they foot the bills for the Standing Judicial Committee, among other things). However, it would lower expenses and allow for greater parity between the number of ruling and teaching elders conducting the church’s business. As Benjamin Shaw argued, the interests of the people who want “more seats at the table” (Shaw only mentions women, but probably this is true of the other groups mentioned; this certainly seems to be Shaw’s drift) would be served better by ruling elders than by teaching elders. Greater parity means they have a greater voice.

On the funding plan itself, I have been of two minds. On the one hand, Ligon Duncan’s arguments are very plausible. The Administrative Committee needs funding, and all too often, we have been going about things in a congregational way. On the other hand, critics who argue that the plan constitutes a violation of conscience have a point. Personally, I am not persuaded by the critics. Why would this arrangement violate a person’s conscience any more than the current registration fee does? The response is that the Administrative Committee is a denominational agency, and that we are setting a precedent by making funding of the hierarchy mandatory. This is plausible, but we still make funding of the denominational agency mandatory through registration fees for GA. This problem, again, would be alleviated through a delegated assembly. As many have said, connectionalism has to go both ways. It cannot only be a grass-roots movement from bottom up. Otherwise, we are just congregationalists with some Presbyterian tendencies.

Some of the more controversial wording of the SP was changed. Other NAPARC denominations will be happy to know that commissioners called early for eliminating language about leaving NAPARC (North American Presbyterian and Reformed Council). So also was the language that could implied a safe haven for heretics to propagate their errant views with no accountability. More “seats at the table” cannot be granted constitutionally, and so this language also dropped out.

I was pleased to see that the Northwest Georgia Presbytery’s proposal (calling for greater attention to the traditional ordinances) passed, although I was disconcerted to see that it did not function as a substitute for the SP. Very clearly, it was intended that way. The overture had everything to do with how one goes about doing God’s will in the church. Is it by some strategic plan, or is it by the means of grace God has instituted? So now the PCA has in effect said that we need the means of grace plus this strategic plan in order to succeed as a denomination.

The PCA Back in the Day

Since everyone in NAPARC is thinking about the PCA’s General Assembly meeting this week, Old Life turns back the clock with a series of essays written in response to the 2010 General Assembly’s adoption of its “Strategic Plan.” (Warning: assessments may be as dated as the author’s biographies.)

The first came from Jason Stellman, who was then pastor of Exile Presbyterian Church in Woodinville, WA. His essay was “The PCA Has Issues.”

Much like the kid brother of a member of your group of friends growing up who desperately wanted to fit in with the older guys, so the PCA has begun to display a similarly desperate tendency to seek the approval of those whom we seek to impress. The problem, of course, is that it is unclear just whose approval we’re seeking–it may be that of other missionally-minded churches, it may be that of the culture itself. But either way, like that kid brother, those who crave affirmation just end up annoying the rest of us who couldn’t care less.

It’s not that we Old School Presbyterians don’t care about pleasing anyone, of course. We certainly seek the approval of Jesus Christ in whose name we minister each Lord’s Day. Here’s the thing, though: Jesus doesn’t make me feel bad because my church is small; Jesus doesn’t chide me for not having transformed my city into the kingdom of God on earth; and Jesus doesn’t make me feel guilty because of all the white people who show up for church each Sunday (whites are fine in the suburbs, but ethnics are needed in The City, where real ministry happens). My point is that it is the smile of God that we should be seeking, not street cred (and God smiles at faithfulness, not necessarily at nickels and noses).

Why the rant? The reason is simple enough: the PCA’s Strategic Plan, the points of which were adopted at this summer’s General Assembly, represents the latest in our denomination’s hand-wringing over how supposedly irrelevant we have become (I mean, we didn’t even grow numerically in 2009!). Whether it’s withdrawing from NAPARC (which the original version of the Plan suggested) or shifting our discussions of worship and mission from the context of church courts to “safer places” with “more voices at the table,” the fact is that the movers and shakers of the PCA have determined that we’ve got to do something (did I mention that we didn’t grow in 2009?).

My aim here is not to discuss the Plan in detail, but rather to direct attention to what it says about us as a denomination. It seems that the everyday and ordinary are just fine when we’re surrounded by tokens of blessing and bounty, but when those outward, visible tokens disappear then we must come up with something out of the ordinary to make up the slack and restore what the locusts have eaten.

What many of the PCA’s leaders have failed to appreciate is the degree to which a church’s philosophy of ministry is indicative of its understanding of the Christian life more broadly. I’ve been told that Jewish rabbis are fond of saying “Our calendar is our catechism,” by which they mean that their faith is instilled and passed down by means of the regular rhythm of the synagogue’s times of worship and prayer. A similar principle is true in Christianity: we communicate the what by means of the how. If the Christian life is to be understood as one of marked and measurable success, then what better way to convey that expectation than by inventing new strategies and methods to deal with perceived failure? And contrariwise, what lesson is conveyed by an insistence upon the ordinary means of grace than that the Christian life is characterized by some ups but lots of downs, by smatterings of already amid plenty of not yet?

This ordinary-means-of-grace ethos was captured beautifully by PCA pastor Jon Payne, who submitted to the Assembly what was originally intended as an alternative to the SP. Its points include: a renewed commitment to exegetical, God-centered, Christ-exalting, Holy Spirit-filled, lectio-continua preaching; to the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper for the spiritual nourishment, health and comfort of the elect; to private, family and corporate prayer; to–and delight in–the Lord’s Day; to worship God according to Scripture; and to sing the Psalms in private, family, and public worship.

The first thing one is likely to notice while perusing Payne’s proposal is just how mundane and unexciting it all sounds. Absent are the clarion calls for the transformation of society and the democratization of the church’s leadership, and in their place we find a renewed commitment to sacraments, psalm-singing, and Sabbath-keeping. If you think about it, what lies at the back of the disagreement on the part of the Old-School opponents of the SP and its New-School supporters is the relationship of the church’s mission and marks. As the (original) SP’s talk of leaving NAPARC suggests, it is apparently not enough for a congregation to exhibit the marks of a true church if those congregations are not sufficiently “missional.” But aren’t the preaching of the gospel, the administration of the sacraments, and the practice of church discipline themselves the mission? And isn’t this what NAPARC churches do?

The mere exhibiting of these marks, however, hardly sounds “strategic.” A strategy, after all, is “a plan, method, or series of maneuvers or stratagems for obtaining a specific goal or result.” If you want to lose twenty pounds this year, you had better implement a strategy. But it is here that the analogy breaks down with respect to Christ’s church, for while the means are given to the church’s officers, the results are out of our control. “The winds blows where it will,” Jesus tells us, and though we can see its effects we cannot harness its power or predict it path. “So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.” This admission does not breed apathy, any more than an appreciation of divine sovereignty breeds prayerlessness. On the contrary, it is precisely because we believe that God is in control that we bring our petitions to him, and likewise, it is precisely because we believe that God will add his blessing to the means of grace that we insist so strongly upon their centrality in the life and ministry of the church. Last I checked, Jesus didn’t tell his disciples to go out and build him a church, but promised rather to be the Architect himself: “On this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell will not prevail against it.”

But this is risky business, this stepping back and allowing Jesus to determine the success and relevance of the church. Size matters, at least in the minds of most American evangelicals, and nickels and noses simply cannot be guaranteed by such out-of-date methods as preaching and serving communion. But shouldn’t this be the point where faith comes in? If strategies are intended to bring about specific results, then what’s the point of faith (or the Holy Spirit, for that matter)? You get on the treadmill and cut out the Oreos, and you’ll lose that weight. You adopt a culturally savvy mission, and you’ll grow a relevant church. But all this talk of strategies and expected results makes the church sound like a mere human institution beholden to the laws of the free market rather than a Body whose growth comes in spurts unpredictable.

It’s gut-check time for the PCA. Are we as a denomination going to trust in the tried and true means of grace that Christ has ordained for the growth of his church, and commit our expectations concerning that growth to the Spirit who alone can bring it about? Or, are we going to fall into the old trap of sacrificing the church’s marks on the altar of “mission,” as defined by the cultural guardians of all things relevant? Many of our Reformed forefathers stood at this very same crossroads and blinked, and we have their failures to thank for the liberal Protestant churches that litter the current landscape. The temptation to innovate is strong, but what we must remember is this: choosing the old paths is what makes us a church, while seeking the novel is what will makes us a cliché.

The Latest Nicotine Theological Journal

The October 2023 issue just went out to “subscribers.” The issue will be posted at this website in three months — but the way the editors keep schedules, don’t hold your breath.

For now, here’s a taste of the really late latest:

Celebrity Pastors Think, We Don’t Have To

Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind came out in 1994 about midway in the era of peak evangelical intellectualism. This was a period, 1980 to 2010, when evangelicals embraced the scholarly task with a zeal not before evident among born-again Protestants. The former date – 1980 – marked the founding of the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals (ISAE) at Wheaton College. Launched by Mark Noll and Nathan Hatch, with inspiration from George Marsden, at the Harvard of the Bible belt, the ISAE sponsored important scholarship from historians who studied American Protestantism. The center of energy at Wheaton became a path for evangelical colleges (most notably Calvin College – now University) to receive grants from foundations in support a variety of research projects from scholars across the disciplines. The year 2010 is notable for the cover story in The Atlantic, “The Opening of the Evangelical Mind,” by the Jewish-American sociologist, Alan Wolfe, that highlighted the strides evangelicals had made in the corridors of American higher education.

Coming mid-way in this golden age of evangelical scholarly output, Noll’s Scandal warned about not going back to old ways of thinking. The old evangelical habits – perhaps characterized as hyper-spiritualized or biblicistic – led to fundamentalist fears of theological compromise, revivalist fixation on soul-winning, and premillennialist obsession with Christ’s immanent return. Each of these intellectual tics and spiritual instincts undermined the mental discipline required for genuine scholarship. At the same time that Noll was warning about the past, he was also cheering on contemporary evangelical scholars and hoping college and seminary administrators would nurture even more scholarship. It did not hurt that this was a period when foundations like Pew and Lilly were bankrolling evangelical institutions. Pew was the most significant and reflected an effort to move beyond theological education into the arts and sciences. The Lilly Endowment’s support, typically reserved for mainline Protestants, was a recognition that evangelical scholars were catching up to scholars within the network of established Protestant institutions.

Since 2010 the evangelical mind has been buffering (like when your web browser has too many cookies). The closing of the ISAE in 2014 was one indication that either evangelicals did not have scholars to carry on what Noll and Hatch had started or that leaders of evangelical colleges no longer thought scholarship was sufficiently important for Christian higher education. Christianity Today’s decision to cease publishing Books & Culture, was another indication of evangelical mental fatigue. The magazine had aspired to be evangelicalism’s New York Review of Books. Even so, Books & Culture had always depended on subsidies from its parent company or from foundations. By 2016 the heads of Christianity Today gave up on the dream of a heady evangelical publication that monitored books and ideas.

After all of this thinking, did evangelical scholarship prevail over the scandal about which Noll warned? Do evangelicals think about the world and their faith better now than they did before the evangelical renaissance? One test is to see whether evangelicals read non-evangelicals for insights into the world. After all, evangelical scholars, if they are doing good scholarship need to keep abreast of the best scholars in their field – most of whom are not Christian. If evangelical scholars know how to use and evaluate the work of non-Christians, can ordinary Protestants in a similar way take counsel and instruction from pundits and observers who make no profession of faith?

Tim Keller may have benefitted as much as any pastor from the flowering of the evangelical mind. His ties to the seminary world (Gordon-Conwell, Westminster, Reformed) prevented his easy circulation among the historians and philosophers at colleges who were at the forefront of the evangelical mind. But Keller’s years of greatest influence coincided with those of peak evangelical mind. The atmosphere of evangelical scholarship made plausible a pastor in the wealthiest and most influential city in the world conducting a ministry that made Christianity seemingly plausible to secular elites. Evangelical minds also encouraged pastors to have a take on contemporary affairs and to do so in a distinctly Christian voice.

In 2020, the most recent Year Zero, Keller wrote a series of articles on the current things that were agitating the American people and the rest of the world (thanks in part to a global obsession with Donald Trump). The topics that absorbed Keller’s attention were Race, Racism, and Justice. The last article in the group – the big finish – was “A Biblical Critique of Secular Justice and Critical Theory.” This was precisely the sort of thinking the evangelical mind was supposed to produce. Keller spent 6,900 words – the average length of the NTJ – showing how he evaluated social justice as a Christian thinker. . . .

Christian Church (not Christian Nation) even in the Psalms?

After listening to Chris Gordon and Brad Isbell talk about Christian nationalism and two-kingdoms theology (where it did sound like Chris said “R two Gay” instead of “R two K”), I was surprised to read Martin Luther this morning on Psalm 87. That Psalm reads:

1 On the holy mount stands the city he founded;

2 the Lord loves the gates of Zion

more than all the dwelling places of Jacob.

3 Glorious things of you are spoken,

O city of God. Selah

4 Among those who know me I mention Rahab and Babylon;

behold, Philistia and Tyre, with Cush —

“This one was born there,” they say.

5 And of Zion it shall be said,

“This one and that one were born in her”;

for the Most High himself will establish her.

6 The Lord records as he registers the peoples,

“This one was born there.” Selah

7 Singers and dancers alike say,

“All my springs are in you.”

Here is how the two-kingdom Luther introduced the Psalm:

The 87th psalm is a prophecy of the Holy Christian Church, that it shall be a city as wide as the earth is, and in it shall be born Ethiopians, Egyptians, Babylonians, Philistines, residents of Tyre, and people of other lands and tongues. This shall all happen through the Gospel, which shall preach marvelous things of God, namely the knowledge of God, how one may come to God, be freed from sin, and be saved from death, through Christ. And the worship of God in this city shall also be singing and dancing, that is, they will proclaim, praise, and thank God’s grace with joy. In that city, no Moses shall plague and torment us with his Law.

Here is a sixteenth-century two-kingdom advocate, not someone from the 1990s reacting to theonomy, reading the city of God in the Old Testament and identifying it not with empire, kingdom, or nation but with the church. Of course, Luther needed a Christian magistrate (a Roman Catholic one, to boot). Without one he would have been executed. But his thoughts were on matters other than a Christian politics when looking for the kingdom of God.

What may be especially upsetting to those who subscribe recent versions of Christian nationalism is Luther’s throwing down a welcome mat at the door of the church to all tribes and ethnicities. It sure must seem odd to think of the Christian church as multi-ethnic and multi-racial when some insist that ethnic homogeneity is necessary for a Christian nation.

The jab at Moses’ law could, however, confirm the anti-nominan reputation of two-kingdom proponents. No one’s perfect.

After All These Years It’s Still Theonomy vs. 2K

From David VanDrunen’s review of Brad Littlejohn’s Called to Freedom: Retrieving Christian Liberty in an Age of License.

On a general level, Littlejohn at times seems to jump from the observation that without certain virtues, people won’t use their outward freedoms well the conclusion that civil officials may therefore legitimately restrict these freedoms. But although the observation is valid, the conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow. On what basis do civil officials have authority, for example, to restrict market transactions or prohibit non-Christian religions for the “common good” when no force or fraud is involved?

Perhaps instructive is Littlejohn’s understanding of civil authorities as “fathers of their people” who ought to “exercise paternal care” for them. There is some similarity between fathers and civil magistrates, but there are also so many differences that it seems dangerous to invoke this analogy as grounds for specific government regulations. For one thing, fathers have extensive authority over even minute details of their children’s lives. On that analogy, civil officials could regulate almost anything. Perhaps even worse, the analogy presumes that citizens are children. This seems to work at cross-purposes to Littlejohn’s oft-stated ideal that citizens be morally mature and self-governing.

We see another reason for Littlejohn’s openness to extensive government authority in his support for the “classical Protestant theory of religious liberty.” He explains this theory as follows: In Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2, God calls civil authorities to punish evil and praise the good (although not, contra Littlejohn, to “reward” or “promote” the good). The natural moral law defines what is evil and good. The Ten Commandments summarize the natural moral law. This means, in Littlejohn’s telling, that civil officials have authority to enforce the “full scope” of the Ten Commandments.

But there’s a problem with this reasoning. The fact that civil officials punish evil and praise the good doesn’t entail giving them jurisdiction over all that is evil and good. What’s more, the natural moral law—what we know about right and wrong from the testimony of nature—doesn’t provide nearly enough guidance for civil authorities on which religion to promote or restrain. The testimony of nature itself doesn’t reveal truths about the Trinity, atonement for sin, the church, and other core matters.

At best, Littlejohn’s belief that civil magistrates may restrain non-Christian worship and proselytizing needs more extensive argument. Could Scripture provide it? One might appeal to the precedent of Old Testament kings under the Mosaic theocracy, which is exactly what many pre-modern Christian theologians did. But since contemporary political communities are not God’s holy people, in redemptive covenant with God, such appeals are highly problematic. Littlejohn briefly glances at these issues but doesn’t really discuss them.

At one point, Littlejohn states that Christians can disregard ungodly rulers when they issue clear commands to transgress Scripture. Yet in other cases, he argues, we can cheerfully tolerate them. Are there really no other instances when Christians might justly disregard such rulers? When rulers act contrary to the laws of their own community, for example, shouldn’t citizens commit to following the law instead?

Littlejohn himself, when discussing political freedom as liberty under law, appeals to the classical notion that law should be consensual. In other words, it ought to emerge from “time-tested customs and communal practices, unwritten laws that written laws should respect.” This is indeed a noble idea. But if we take it seriously, it requires the people to have a great deal of independence to forge their own ways of life, which entails corresponding limitations on civil authority. It would have been interesting to see Littlejohn develop this theme and reflect more on its implications.

Even if Littlejohn’s conception of the extent of civil authority needs further defense, his larger perspective on Christian liberty is solid, insightful, and sometimes eloquent. Called to Freedom usefully clarifies the issues at stake, even if it doesn’t settle all of them. It should stimulate, but not end, important discussions on what it means to be free.

Summer 2023 NTJ Available (pdf)

To repeat, this is not a typo. The Summer 2023 issue is now available at Oldlife.org. Huzzah? Maybe not.

In it, readers will find a case for shorter (8-10 years) pastorates as opposed to the increasingly common one of decades long tenures for pastors. Here is an excerpt:

In lengthy pastoral tenures a congregation becomes so comfortable with their minister (and vice versa) that the identity of the place has more to do with the people in this particular setting than with the denomination. Such a situation makes it harder to find a successor to the long-term pastor. A congregation might need to conduct a lengthy search to find that one person who has just the right gifts for this group of Christian. At that point, the congregation might well forget the nature of the ministry according to the common standards of the denomination. They might want “our guy” more than, for instance, a generic Presbyterian pastor who can do all the things that a man trained for the Reformed ministry is supposed to do. The congregation might forget what it means to belong to a certain communion because it functions largely within its own local context with its own pastor. A pastoral search could then depend more on personal qualities than on the demands of presbytery and the denomination’s corporate witness.

Conversely, expectations for relatively short pastorates, say from five to seven years, likely nurture a sense of belonging to a wider communion in which ideally all of the ministers should be able to serve in any congregation. Instead of building up a kind of co-dependency between minister and congregation thanks to a long tenure, a series of medium-term calls may encourage church members to deepen their membership in the broader communion beyond the congregation.