Not even development of doctrine can keep up with the flips and flops, the yings and yangs, of English-speaking Roman Catholics. Massimo Faggioli provides a bird-watchers guide:

There is, for example, a new wave of ultramontanism that looks to an idealized conception of Rome for its points of reference. There is also a related resurgence of “integralism,” inspiring conferences at the University of Notre Dame and Harvard. The new integralism takes a step beyond the more tentative Catholic post-liberalism, or the simple proclamation of the crisis of liberal Catholicism. Integralism is the attempt to imagine for the Catholic Church—but also for the world in which the church lives—a future that rejects the “liberal” separation between temporal and spiritual power, and subordinates the former to the latter.

According to Sacramentum Mundi (first published between 1968 and 1970, and now available online—its general editor was Karl Rahner, SJ) integralism is

the tendency, more or less explicit, to apply standards and directives drawn from the faith to all the activity of the Church and its members in the world. It springs from the conviction that the basic and exclusive authority to direct the relationship between the world and the Church, between immanence and transcendence, is the doctrinal and pastoral authority of the Church.

Here one can detect a subtle difference between the classic definition of integralism and its twenty-first-century variety. This new strain is focused almost exclusively on the political realm. In fact, what it resembles most is another phenomenon of nineteenth-century Catholic culture: intransigentism—the belief that any concession to, or accommodation with, the modern world endangers the faith. Unlike mere conservatism, which values elements of the past and seeks to preserve them, intransigentism rejects the modern outright and preemptively. This has consequences for the theological thinking of Catholics who today call themselves integralists, traditionalists, and ultramontanists. For these Catholics, the past sixty years—and especially Vatican II—either do not matter at all or matter only if they can be interpreted as a confirmation of the church’s past teaching.

Roman Catholic liberals also are hardly steady:

It is interesting how different the liberal Catholicism of the nineteenth century is from the liberal Catholicism of today, and how similar the Catholic intransigentism of the nineteenth century is to the intransigentism of today. Liberal Catholicism today is much more accepting of individualistic, bourgeois society than it was in the nineteenth century, when it had a more prophetic edge. But intransigentism hasn’t really changed much in the past 150 years, especially when it comes to the question of the confessional state—a question on which the church’s official teaching has changed during this period. It would be interesting to ask the proponents of this kind of Catholicism what they make of the plight of Catholics who have to live as minorities under integralistic non-Christian confessional regimes, and why those Catholics do not seem to be so afraid of liberalism.

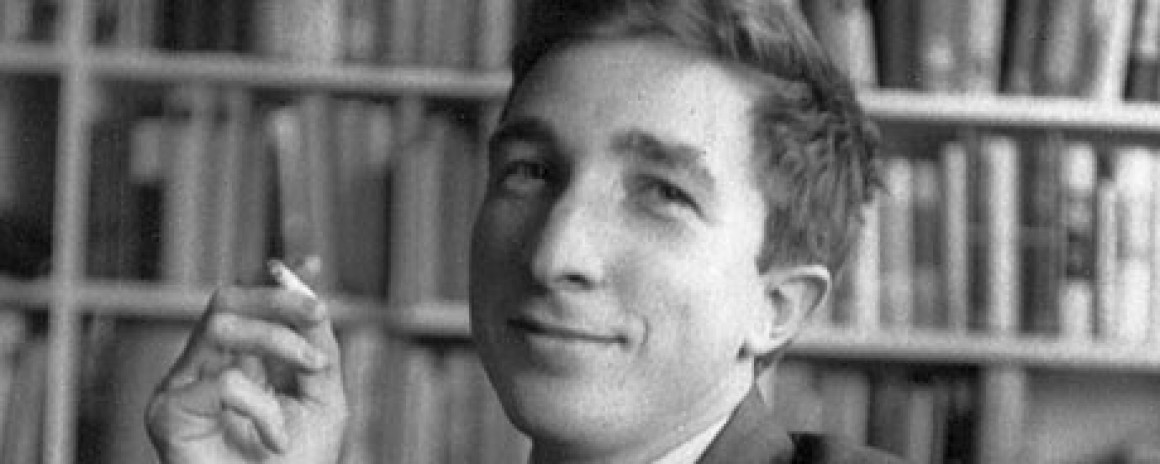

Faggioli may regard himself as closer to the mainstream of Roman Catholic thought thanks to his regard for Pope Francis and his Italian background. But when you ponder all the changes in Roman Catholic teaching about various aspects of modern society since Vatican II, you hardly see the sort of continuity to which the Villanova University professor aspires. Roman Catholics in the U.S. certainly have their moments. But it is not as if the bishops, the Vatican, or the papacy has stayed on track. Roman Catholics can pick their favorite pope after World War II — John XXIII, Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, or Francis — according to their reading of the tradition, the modern world, and personal preference.

It’s almost as chaotic as Protestants reading the Bible.