James Scott’s book, Seeing Like a State (1998) came up in this fascinating discussion of public policy, health systems, government, expertise, and legitimate political authority. The following is from a review of Scott’s book in The New Republic, May 18, 1998 (“More is Less”, by Cass R. Sunstein). This is precisely what state governors and their advisors are doing during the COVID-19 pandemic:

German psychologist named Dietrich Dorner has done some fascinating experiments designed to see whether people can engage in successful social engineering. The experiments are run by a computer. Participants are asked to solve problems faced by the inhabitants of some region of the world: poverty, poor medical care, inadequate fertilization of crops, sick cattle, insufficient water, excessive hunting and fishing. Through the magic of the computer, many policy initiatives are available (improved care of cattle, childhood immunization, drilling more wells), and participants can choose among them. Once initiatives are chosen, the computer projects, over short periods of time and then over decades, what is likely to happen in the region.

In these experiments, success is entirely possible. Some initiatives will actually make for effective and enduring improvements. But most of the participants—even the most educated and the most professional ones—produce calamities. They do so because they do not see the complex, system-wide effects of particular interventions. Thus they may recognize the importance of increasing the number of cattle, but once they do that, they create a serious risk of overgrazing, and they fail to anticipate that problem. They may understand the value of drilling mote wells to provide water, but they do not foresee the energy effects and the environmental effects of the drilling, which endanger the food supply. It is the rare participant who can see a number of steps down the road, who can understand the multiple effects of one-shot interventions into the system.

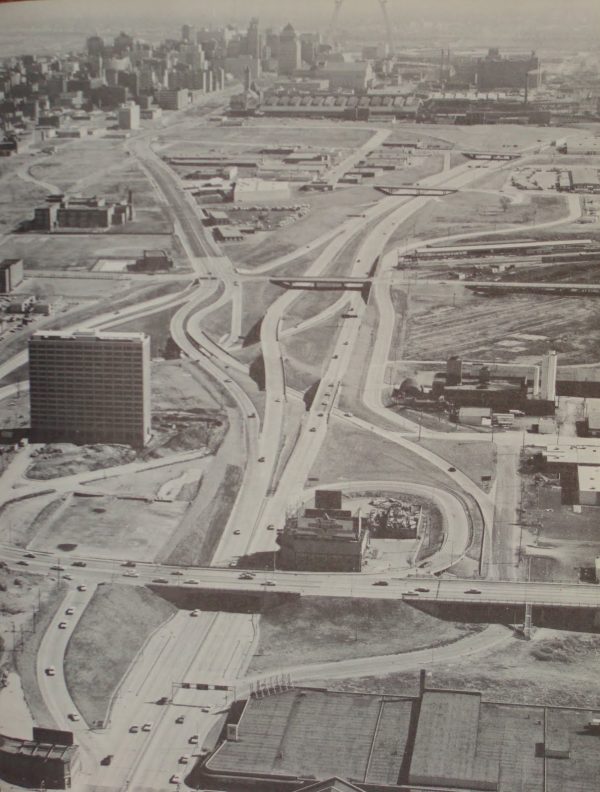

These computer experiments have countless real-world analogues. As everyone now knows, an unanticipated problem with mandatory airbags is that they result in the deaths of some children who would otherwise live. Less familiarly, new antiterrorist measures in airports increase the cost of air travel, thus leading people to drive instead, and driving is more dangerous than traveling by air, so more stringent antiterrorist measures

may end up killing people. If government wants to make sure that nuclear power is entirely safe, it should impose tough controls on nuclear power, but those controls will increase the price of nuclear energy, which may well increase the use of fossil fuels, which may well create the more serious environmental problems. . . .On Scott’s view, the failed plans and the thin simplifications ignore information that turns out to be crucial. To be sure, an all-seeing computer, capable of handling all relevant information and envisioning the diverse consequences of different courses of action, may facilitate tyranny. But it need not blunder. This is the real lesson of Dorner’s experiments, for which Scott has provided a wealth of real-world counterparts. And this is not

the end of the story. Dorner also demonstrated the possibility of successful planning by those who are attuned to long-range effects. Scott’s analysis would have been improved if he had compared success with failure, and given a clearer sense of the preconditions for success.Still, Scott’s advice is far from useless. It can be applied to contexts far afield from those that concern him here. His case studies help explain, say, why national regulation tends to work better when it consists of altered incentives rather than flat commands. Some of the most successful initiatives in American regulatory law have consisted of efforts to increase the price of high-polluting activities; and some of the least successful have been rigid mandates that ignore the collateral effects of regulatory controls. Scott’s enthusiasm for metis also suggests that certain governmental institutions will do best if they act incrementally, creating large-scale change not at once, but in a series of lesser steps. We might think here not only of common law, but also of constitutional law. Many judicial problems derive from a belief that judges can intervene successfully in large-scale systems (consider the struggles with school desegregation in the 1960s and 1970s), and many judicial successes have come from proceeding incrementally (consider the far more incremental and cautious attack on sex discrimination in the same period).

And Scott also offers larger implications. A society that is legible to the state is susceptible to tyranny, if it lacks the means to resist that state; and an essential part of the task of a free social order is to ensure space for institutions of resistance. Moreover, a state that attempts to improve the human condition should engage not in plans but in experiments, secure in the knowledge that people will adapt to those experiments in unanticipated ways. Scott offers no plans or rules here, and a closer analysis of the circumstances that distinguish success from failure would have produced greater illumination. But he has written a remarkably interesting book on social engineering, and be cannot be much faulted for failing to offer a sure-fire plan for the well-motivated, metis-friendly social engineer.