From the Archives: Nicotine Theological Journal, January 1999

Mere Confessionalism

“In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, charity.” This is the motto of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church. (The expression itself is of some antiquity, and it may date back as early as St. Augustine.) At its founding in 1981 the EPC adopted a modern language version of the Westminster Confession of Faith as its doctrinal standard. At the same time it also adopted an eight- point “Essentials of our Faith” summary statement. The latter contains boiler-plate evangelical affirmations on the Bible, God, Christ, sin, salvation, and eschatology, in language that is mildly and non-militantly Calvinistic.

Are these two documents competing doctrinal standards? An interesting debate is playing out in the EPC now regarding what confessional status, if any, its “Essentials” possess and how they relate to the Westminster Confession. The “Essentials” themselves end this way: “These Essentials are set forth in greater detail in the Westminster Confession of Faith.” But rather than solve the question, that ambiguous language only heightens the confusion. Does it mean that the WCF itself – taken as a whole – is the “Essentials” in fuller form, or merely that these eight affirmations can each be found there as well? Are the “Essentials,” in other words, what the church really believes? Should the emphasis fall on the first or second word in the denomination’s name, “Evangelical Presbyterian Church”?

MOST CONSERVATIVE Presbyterians would likely contend that the EPC has misidentified the essentials of the faith. After all, it is open to women in church office and the ongoing exercise of the charismatic gifts. At the same time, the EPC debate is instructive, because its conservative Presbyterian critics also tend to employ some form of what can be called the hermeneutic of essentials, of identifying what the church may or may not tolerate. Presbyterian theologian, John Frame, for example, in urging the creation of leg room within the confessions, laments that “the whole question of what is and what is not tolerable within the church has not been systematically analyzed.”

Frame’s quest is not new. Efforts to isolate the “essentials” within the confession are almost as old as Presbyterianism itself. Frequently, it has been the progressives who have been eager to speak of a “system of doctrine,” in order to permit their deviation from the Confession and catechisms of the church. By “system” they mean the Confession “in-as-much” as what the Confession teaches is biblical. In this fashion, Presbyterian officers hold line-item vetoes to the church’s Constitution, and the church had erected a Confession-within-the-Confession.

But it is not only progressives who speak this language. In efforts earlier in this century by conservative Presbyterians to preserve the essence of historic Christian orthodoxy, some upheld the minimal necessity of the “five fundamentals” of the faith. The unintended effect was to reduce the “essential and necessary” articles of the church’s constitution to just five.

Especially of late the rhetoric of essentials is invoked in order to separate the Bible from the Confession in the name of the Reformation principle of sola scriptura. (Indeed, often it is phrased in the language of liberating the Bible from the confession.) Increasingly Presbyterian officers seem to be declaring, “never mind the Confession, show me where that is taught in Scripture.” But for Presbyterians, an officer is committed to sola scriptura precisely to the extent that he is a Confessionalist. Confessionalism does not eclipse the doctrine of sola scriptura. Rather, a confession is the necessary means for the church to uphold Biblical authority. The Presbyterian way to point to the doctrine of Scripture is to refer to the Confession.

FRAME DESCRIBES THIS VIEW AS chauvinistic. “Although I am a Presbyterian,” he writes, “I confess that I do not share [the] desire for us always to ‘look like Presbyterians’ before the watching world.” In context, Frame’s concern is specifically about worship, but by implication his views bear upon the relationship between The Nicotine Theological Journal will likely be published four times a year. It is sponsored by the Old Life Theological Society, an association dedicated to recovering the riches of confessional Presbyterianism.

IN DESCRIBING HIS STUDENT days at Westminster Seminary (in the early 1960s), Frame recalls two features of that course of instruction: it lacked an overt “confessional or traditional focus” and there was a spirit of creativity and openness in theological reflection. He goes on to make a startling admission: “After graduation I became ordained in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, and I confess I was rather surprised at the seriousness with which my fellow ministers took the confessional standards and the Presbyterian tradition. Eventually I became more like my fellow Orthodox Presbyterian . . . elders, but not without some nostalgia for the openness of theological discussion during my seminary years.”

Our point is not to critique WTS or any other seminary. And whether Frame has described with accuracy the curriculum of WTS in the 1960s is not our concern either. But what is revealing is the dichotomy that Frame creates between “perpetuat[ing] and recommend[ing] the confessional traditions” on the one hand (which is where he finds WTS’s education flawed), and a “flourishing of original and impressive theological thought” on the other (where he thinks WTS excelled). This difference he goes on to attribute to Westminster’s understanding of sola Scriptura, which liberated the school from traditionalism and confessionalism.

BUT FRAME’S DICHOTOMY WAS unknown to previous generations of Reformed theologians. Calvin Seminary’s Richard Muller writes the following on the harmony of Scripture and confession: “We need creeds and confessions so that we, as individuals, can approach Scripture in the context of the community of belief.” Confessions function as mediating structures, standing between Scripture and the “potentially idiosyncratic individual” as “churchly statements concerning the meaning of Scripture.” They are “normative declarations spoken from within by the church itself . . . as the expression of our corporate faith and corporate identity.”

Muller’s work on Reformed scholasticism reminds us that there was a time when confessional integrity did not compete with sola scriptura, nor did it impede theological creativity. For the scholastic mindset, Muller notes, “Once a churchly confession is accepted as a doctrinal norm, it provides boundaries for theological and religious expression, but it also offers considerable latitude for the development of varied theological and religious expressions within those boundaries.” According to the Reformers, there is no churchman and there is no theologian where there is no confession. Why is that so unimaginable today? Why has the Reformation confidence in the creeds of the church vanished?

AS WE PREVIOUSLY ARGUED (“Sectarians All,” NTJ 2.2), such anti-traditionalism only serves to locate one within a specific tradition, namely the Enlightenment, and its false claim that an individual Christian, armed with autonomous rationality can approach Scripture from a traditionless perspective. The Reformers, Muller claims, refused to approach Scripture with the false dilemma forced upon the church by its adoption of categories of Enlightenment thought.

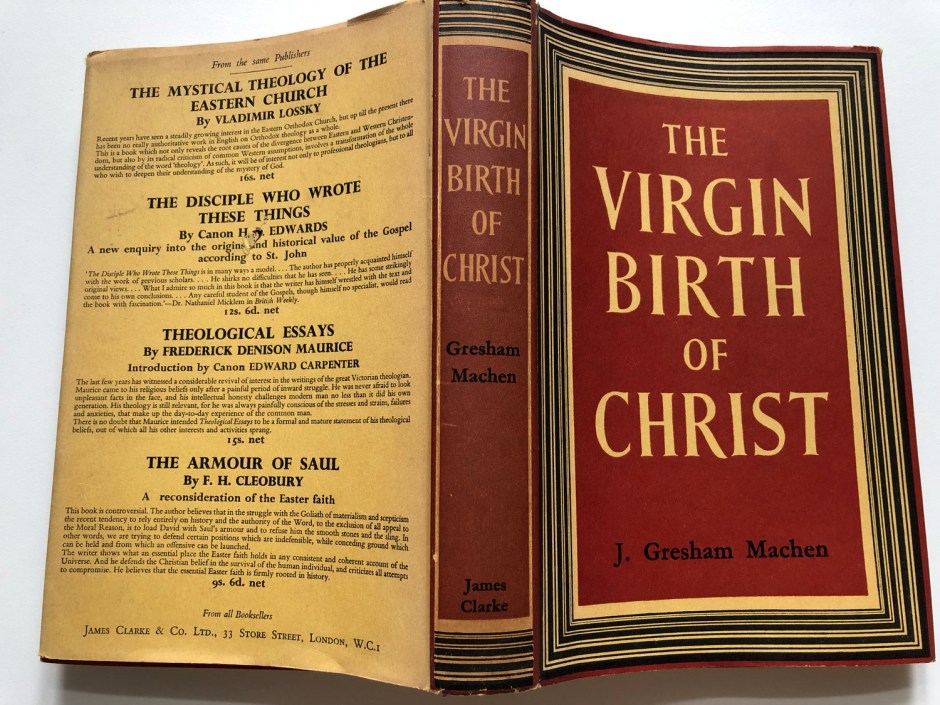

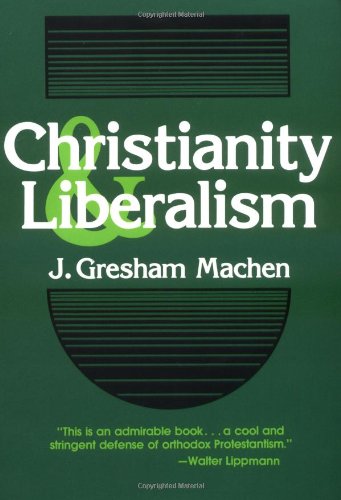

Muller goes on to describe other pressures that our age brings to confessional integrity. He refers to the “noncredal, nonconfessional, and sometimes even anticonfessional and antitraditional biblicism of conservative American religion.” Enlightenment rationality and democratic populism combine to create what Robert Godfrey has diagnosed as the evangelical impulse toward theological minimalism. This minimalism seeks to get as many people to express everything they agree on, and preferrably on one side of one sheet of paper. These affirmations become the truly “essential truths,” and the hills for evangelicals to die on. Godfrey is echoing the thoughts of J. Gresham Machen, who in his essay, “The Creeds and Doctrinal Advance,” described this impulse in the following way:

There are entirely too many denominations in this country, says the modern ecclesiastical efficiency expert. Obviously, many of them have to be merged. But the trouble is, they have different creeds. Here is one church, for example, that has a clearly Calvinistic creed; here is another whose creed is just as clearly Arminian, let us say, and anti-Calvinistic. How in the world are we going to get them together? Why, obviously, says the ecclesiastical efficiency expert, the thing to do is to tone down that Calvinistic creed; just smooth off its sharp angles, until Arminians will be able to accept it. Or else we can do something better still. We can write an entirely new creed that will contain only what Arminianism and Calvinism have in common, so that it can serve as the basis for some proposed new “United Church” . . . . Such are the methods of modern church unionism.

This impulse stands in sharp contrast to what Godfrey calls the theological maximalism of the Reformed, which sought at least in the past to extend the boundaries of the church’s confession in pursuit of the “whole counsel of God.” Moreover, Reformed maximalism and evangelical minimalism differ not only in the size of their creeds but in the very purpose of their creeds. To quote Machen again:

These modern statements are intended to show how little of truth we can get along with and still be Christians, whereas the great creeds of the church are intended to show much of the truth God has revealed to us in His Word. Let us sink our differences, say the authors of these modern statements, and get back to a few bare essentials; let us open our Bibles, say the authors of the great Christian creeds, and seek to unfold the full richness of truth that the Bible contains. Let us be careful, say the authors of these modern statements, not to discourage any of the various tendencies of thought that find a lodgment in the church; let us give all diligence, say the authors of the great Christian creeds, to exclude deadly error from the official teaching of the church, in order that thus the Church may be a faithful steward of the mysteries of God.

BUT IS ALL OF THIS FAIR TO evangelicalism? After all, no less an evangelical icon than C. S. Lewis contended for a “mere Christianity.” Yet Lewis himself was not confused about his beliefs, which he said were found in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. His search for a “mere” Christianity was not an alternative to the creeds of the church. Rather, he likened it to the difference between the halls and rooms of a mansion. “Mere” Christianity may bring one into the hall. “But it is in the rooms, not in the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals.” The “worst of the rooms,” he went on to stress (perhaps thinking of a dimly lit and drearily decorated attic of Calvinistic horrors), is to be preferred over the hall.

Whatever Lewis intended, his words have been hijacked to serve unhealthy purposes. The ambiguities of the expression, “Mere Christianity,” can be found in many of Lewis’ disciples. And when it meets contemporary evangelicalism, there is a volatile mix that may prove lethal to the theological reflection and confessional identity of the church.

CONSIDER TOUCHSTONE magazine, which had recently changed its subtitle from “A Journal of Ecumenical Orthodoxy” to “A Journal of Mere Christianity.” Its editorial purpose is to “subordinate disagreements to the common agreement” because the crisis of our day is so grave. Here we must recognize the debilitating effects of the so-called culture wars on the confessional identity of the church. Abortion, Gay rights, women’s rights, funding for and legal protection of pornographic artists, evolution in the public schools — all of these are battle fronts in the increasingly rancorous struggle over the meaning and purpose of America. And these are the causes to which Christians should devote their energy.

“We need to identify the ‘real enemy’,” urges Touchstone, and that enemy is without, not within. What is said moderately in Touchstone can be found in more virulent form in Peter Kreeft’s Ecumenical Jihad. For Kreeft, mere Christianity may not even be recognizably Christian. The moral decay of America, with all of its leading indicators of spiritual decline, is creating new alliances, even among those of differing religious convictions. The old fashioned Protestant v. Catholic v. Jewish warfare is passe. So great is the threat of secular humanism and so united are we with former antagonists on the really crucial issues, that even evangelical Christians, Kreeft predicts, will eventually arrive at the conclusion that Muslims are on the right side. They may be murdering Christians in Sudan, but at least they are not massacring unborn children. Given the real crisis of our time – the decline of Western Civilization – this is “no time for family squabbles.” This is not merely cultural warfare but spiritual warfare that will unite Protestants, Catholics, Orthodox, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and maybe even an occasional natural-law-advocating atheist.

(Don’t be too alarmed by all this. The Holy Spirit is at work among pious Muslims, Kreeft assures Christian skeptics, and in heaven these Muslims will come to learn that the Allah they served was the God of the Scriptures. What is more, Kreeft goes on to comfort Catholics that Protestants will ultimately come to venerate the blessed Virgin Mary, if not in this life then in the next. So the very ecumenical Kreeft eventually emerges from the closet and is outed by the end of his own book as a good, confessional Catholic.)

TOUCHSTONE MAGAZINE ultimately appeals to experience over doctrine. “Mere Christianity,” it states, is found ultimately not in doctrine but lies in “the character of a man.” Similarly, Kreeft argues that beyond theological differences, we find mere Christianity where there is love. This privileging of experience over doctrine prompts us to wonder whether efforts to arrive at evangelical essentials owe less to C.S. Lewis than to Friedrich Schleiermacher, the 19th-century father of modern theological liberalism.

Fundamental to Schleiermacher’s method was his division between the kernel and husk of the Christian faith. The latter is the practice of Christianity, that which is culturally conditioned, and the former is the “essence of the Christian faith,” stripped of these acculturated accretions. It was this non-negotiable kernel that Schleiermacher desperately sought to preserve. The husk is what is offensive to unbelievers, specifically, 19th-century elites of Protestant Europe. The task of the church, therefore, is to remove the objectionable and make Christianity attractive and relevant.

SCHLEIERMACHER IS NOT alone in this methodology. In our century, Tillich’s “method of correlation” and Bultmann’s program of demythologization likewise restated biblical message in language free from pre-modern superstitions and categories more friendly to modernity. A little closer to home, seeker-sensitive worship owes much to 19th-century liberalism, in order to make church accommodating to unchurched Harry and Sally. All of these are efforts to repackage the Christian faith.

In his book, Rumor of Angels, sociologist Peter Berger says that whenever one engages in this method, one is making a cognitive adjustment to the worldview of modernity. In the case of liberalism, the result can be “a profound erosion of the traditional religious content, in extreme cases to the point where nothing is left but hollow rhetoric.” But however practiced, this adjustment or “bargaining” is always a process of “cultural contamination,” because in the encounter between the church and modernity, modernity always wins.

Berger’s point, of course, is that you cannot adjust the wrappings and leave the core unaffected. But is it a stretch to link contemporary evangelicals with a Schleiermacher? We may not see language like kernel or husk, much less something as ominous as demythologization. But substitute “message” and “method,” and it begins to sound familiar. How many times have you heard it said that we must maintain our message but we must change our method, because the world is changing, and at a dizzying pace at that. Or think about the churches that describe their “philosophy of ministry” in brochures for first-time visitors without reference to their theological standards. And then there is “worship style.” How is it that churches can offer two morning services that are “identical” except for the music? Let us not forget that Friedrich Schleiermacher was as desperate as Bill Hybels to present Christianity in relevant and meaningful ways to a skeptical culture.

IN DAVID WELLS’ TERMS theological liberalism and contemporary evangelicalism both quarantine theology from ministry. By dividing message from method, both permit theological convictions to play a diminishing role in the life of the church. On more and more matters, evangelicals are suggesting that theological considerations are irrelevant, overshadowed by the more urgent need for cultural relevance or evangelistic effectiveness. According to Wells,

It is not that the elements of the evangelical credo have vanished; they have not. The fact that they are professed, however, does not necessarily mean that the structure of the historic Protestant faith is still intact. The reason, quite simply, is that while these items of belief are professed, they are increasingly being removed from the center of evangelical life where they defined what that life was, and they are now being relegated to the periphery where their power to define what evangelical life should be is lost.

SCHLEIERMACHER’S METHOD should serve as ample warning that theological minimalism is a false messiah. It is sure to destroy what it claims to preserve, not only when it is in the hands of liberals, but also when it is practiced mildly by conservative evangelicals. A lowest common denominator is an ecumenical dead end. A Reformed church whose worship disguises its Reformed identity is simply not reformed.

Presbyterians would do better to affirm a “mere” Confessionalism, and regard, along with our ancestors, the standards of the church as liberating and not constrictive. Further, Presbyterians might want to acknowledge, however humbling it might be, that they stand to learn something here from the Lutherans. Our Lutheran counterparts seem far more vigilant in their confessional identity than Calvinists. At a recent gathering of the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals, Missouri Synod theologian, David P. Scaer, struck at the heart of the evangelical dilemma:

Any survival and recovery of Reformation theology cannot be made to depend on a further compromise which identifies an essential core of agreement in order to save it. . . . This kind of agreement immediately puts Lutherans at a disadvantage, since they must concede what makes them Lutherans.

In observing the eager participation of the Reformed in such holy grail pursuits of essentials, Scaer wonders whether the Reformed have made such a suicidal concession. We can hardly improve on Scaer’s conclusion: “Distinctions between essential and non-essential do not belong in the confessional vocabulary.”

Which leads to the unpleasant conclusion that a “confessing evangelical” is a contradiction in terms. Perhaps then Reformed need to cultivate among themselves the same dis-ease for the term “evangelical” as Machen had for “fundamentalist” in his day. Although he reluctantly accepted the term, he couldn’t abide the artificial reduction of a full-orbed Calvinism into a list of fundamentals. So instead of asking what church officers can get away with and how churches can be innovative, Reformed should second Machen: “isn’t the Reformed faith grand!”

“IN ESSENTIALS UNITY; IN NON-essentials, liberty; in all things, charity.” This is a motto that the Presbyterians can embrace. We need not concede it either to charismatic Presbyterians or broad evangelicals, but only if we define essentials in a confessionally self-conscious way. In our standards, there is unity – mere confessionalism. The search for essentials ends when the church adopts her standards. Beyond our confession, there is liberty, and with it openness and even diversity, in theology, worship, and life. And what about charity? By worldly standards, confessionalism does not permit a hermeneutic of charity, for that is a charity of indifference and tolerance. But confessionalism does cultivate a biblical charity that rejoices in the truth, and believes all things.

JRM