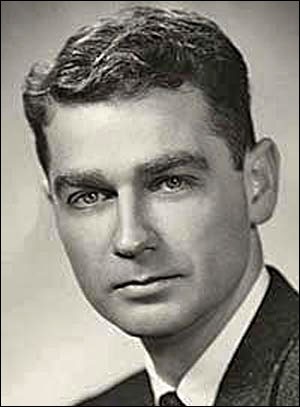

The governor of Oregon and U.S. Senator, Mark Hatfield, died last Sunday. For many evangelicals born after 1970, Hatfield’s name is obscure. But during the 1960s and 1970s he was a model for evangelical political engagement. Only after the rise of the Moral Majority under Jerry Falwell and the Reagan Revolution did Hatfield’s brand of liberal Republicanism disappear as an option for born-again Protestants. But now that a younger generation of evangelicals, recovering from Falwell and Bush fatigue, is looking for a less conservative and (even) more compassionate way of doing what Jesus would do in the public square, reflections on Hatfield’s legacy will likely be positive.

The governor of Oregon and U.S. Senator, Mark Hatfield, died last Sunday. For many evangelicals born after 1970, Hatfield’s name is obscure. But during the 1960s and 1970s he was a model for evangelical political engagement. Only after the rise of the Moral Majority under Jerry Falwell and the Reagan Revolution did Hatfield’s brand of liberal Republicanism disappear as an option for born-again Protestants. But now that a younger generation of evangelicals, recovering from Falwell and Bush fatigue, is looking for a less conservative and (even) more compassionate way of doing what Jesus would do in the public square, reflections on Hatfield’s legacy will likely be positive.

Hatfield makes an important appearance in From Billy Graham to Sarah Palin as a representative of what might have been had Falwell and the Moral Majority not come along. As important as Hatfield was, especially by inspiring the likes of Jim Wallis, he committed the same error as Falwell — baptizing politics in the name of Jesus. Here is an excerpt from the book:

Hatfield initiated any number of pieces of legislation on domestic and foreign policy that struck many as naively idealistic. From American consumption of food, and dependence on fossil fuels to the United States’ production of a nuclear arsenal, Hatfield was often ready with proposals that reflected his own understanding of what would Jesus do if he were an American Senator. Aside from legislative proposals, the Oregonian also used his own limited bully pulpit to prick the conscience of fellow Americans. Two resolutions from the 1970s stand out. In 1974 Hatfield called for a National Day of Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer on which Americans would humble themselves, acknowledge their dependence on their creator, and “repent of their national sins.” The Senator’s home newspaper referred to the proposed day as the time “we all eat humble pie.” The same year, Hatfield proposed a “Thanksgiving Resolution” that would have called upon Americans to identify with the world’s hungry, and encouraged fasting on all holidays between Thanksgiving Days of 1974 and 1975. To publicize this resolution, Hatfield hosted a luncheon in the Senate where eaters were treated to a one-course meal consisting of a hard roll.

Hatfield’s political sensibility made no sense to conservatives leaders in the GOP but it resonated with the young evangelical desire for a religiously motivated politics. In several books, such as Between A Rock and A Hard Place, Hatfield insisted that politicians and citizens who followed Christ should be committed to four basic ideals: identifying with the poor and oppressed against exploitative institutions and social structures, opposition to all forms of violence and militancy, resisting a materialistic life-style, and understanding political authority as essentially a form not of rule but service. “Our witness within the political order must hold fast,” Hatfield wrote, “with uncompromised allegiance, to the vision of the New Order proclaimed by Christ.” As such, the role of the Christian politician was always prophetic — the Senator drew much inspiration from the case of the Old Testament prophet, Jeremiah. “Our allegiance and hope rest fundamentally with [Christ’s] power, at work in the world through his Spirit, rather than in the efficacy of our world’s systems and structures to bring about social righteousness in the eyes of God.”

For Hatfield, whose close exposition of the Bible was more substantial than most of the evangelicals who were writing about politics, a fundamental tension existed between Christianity and politics. This world’s structures of governance and economic productivity were essentially corrupt. Rather than regarding the role of the civil magistrate as one of restraining such evil until the return of Christ and the establishment of a new order, Hatfield believed the Christian politician’s duty was to implement those longed-for patterns of justice and righteousness in the present. As utopian as such an ideal might appear, the Oregonian’s reliance on the Bible forced evangelicals to take him seriously. For the younger evangelicals, and especially those attracted to an alternative form of politics, Hatfield’s arguments expressed exactly the themes that should characterize Christian social concern. But even older evangelicals, who were more comfortable with the label of conservative and who channeled their political energies into the GOP, could not dismiss Hatfield because of his standing in the Senate and his appeal to Scripture. If evangelicals had actually been comfortable with political theories derived from reflection on human nature and the created order, they might have dismissed Hatfield as just one more radical idealist who happened to know his Bible. Because he spoke the language of Bible-based, Christ-centered social activism and political responsibility, Hatfield was another in a long line of American Protestants who thought he was doing the Lord’s work.