When you have a comprehensive view (w-w) of the world, when you think that your faith informs (or should) everything you do, hard are those distinctions that 2k so readily supplies, like — this is the church so Christian rules apply, this is not the church so freedom applies.

This problem is no less challenging for Roman Catholics than for neo-Calvinists since both are in the comprehensiveness business of showing how faith relates to EVERYthing a Christian does. Cathleen Kaveny took the comprehensiveness and catholicity of Rome in an arresting direction when she accused Richard John Neuhaus and the First Things crowd of partisanship and undermining the bonds of Roman Catholic unity:

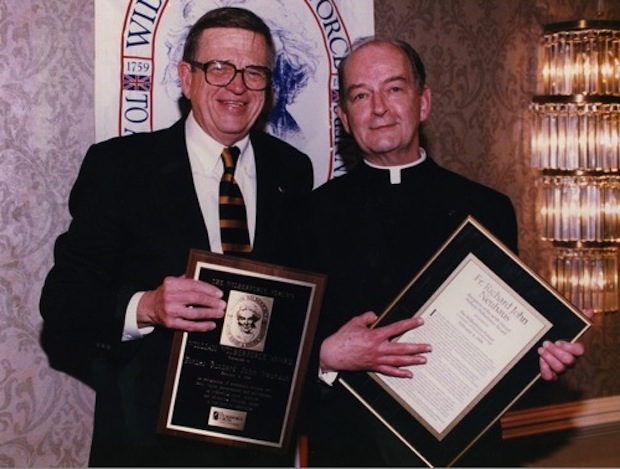

Some conservative Catholics have blamed Pope Francis for sowing division among the members of the Body of Christ. But the charge is more properly lodged against one of the heroes of conservative Catholicism: the late Richard John Neuhaus.

It was Neuhaus, after all, who advanced the view that conservative Roman Catholics have more in common with orthodox Jews and Evangelical Protestants than they do with progressive members of their own religious communities. In fact, that view was an operational premise of First Things magazine under his leadership. This approach is based on a thoroughly distorted view of religious realities and commitments.

Does honoring Jesus as the Son of God count as a commonality? Like their conservative counterparts, progressive Roman Catholics acknowledge the divinity of Jesus Christ, and find the interpretive key to the Hebrew Bible in the New Testament. Orthodox Jews do not—indeed, must not—treat Jesus as the Messiah foretold in the Book of Isaiah. It would be blasphemous for them to do so.

Does living in the grace imparted by the sacraments count as a commonality? Both progressive and conservative Roman Catholics believe that God’s grace is channeled through the seven sacraments. Many Evangelical Protestants do not have the same view of grace or the sacraments; they often view the Eucharist as a memorial of a past event, not a way of being present with Christ here and now.

In trying to find common ground with evangelicals, then, Neuhaus was not truly Roman Catholic but actually Protestant:

Ultimately, Neuhaus’s focus was on nurturing these commonalities in the American political context—he was building a political movement. For a variety of partially overlapping reasons, conservative Roman Catholics, Evangelical Protestants, and orthodox Jews were inclined to vote Republican in political elections. Along with George Weigel and Robert George, Neuhaus coached Republican politicians in Catholic-speak to win national elections. . . . But here’s the irony of Neuhaus’s project: in treating theological belief and commitment as mere instruments of political will, Neuhaus’s view of religion resonated more with Feuerbach, Marx, and Leo Strauss than with the church fathers. In separating his own church of the politically pure from the hoi polloi of the body of Christ, his ecclesiology better reflects Protestant sectarianism than Roman Catholicism.

For the record, I too took issue with Evangelicals and Catholics Together for putting politics ahead of theology and for locating Christian unity not in ecclesiastical contexts but in parachurch groupings.

But Rusty Reno didn’t particularly care for Kaveny’s shot at Neuhaus. And so he tried to justify finding fellowship among religious people who were political liberals and then got mugged by reality:

many of the founding figures who played such a prominent role in First Things, as well as early readers like me, came to some shared conclusions. We became less and less impressed with the modern conceit that ours is a time of the unprecedented. We became more and more convinced that our traditions contained an inherited wisdom—a divine revelation—that provides greater insight into the human condition than any modern method, mentality, or revolution. Again, in the magazine’s early years, it was an exciting and invigorating to find others who were coming to the same post-liberal conclusions, whether they were Jewish, Catholic, or Protestant.

That is mainly true but does not represent the nature of Evangelicals and Catholics Together. Otherwise, ECT should have been called Evangelicals and Liberal Protestants and Roman Catholics and Mormons and Jews and Stanley Hauerwas Together. But at least Reno recognizes different layers of commonality:

When it comes to many things that are important to me, I have more in common with friends than with my brother. But my brother’s still my brother. It in no way compromises the truth of our fraternal bond for me to link arms with those with whom I have more in common politically, intellectually, or even theologically. The same goes for the sacramental bond that units us in Christ.

That is more or less a 2k point. But a 2ker would not call a magazine about religion and public life First Things. It’s not elegant but Penultimate Things or Proximate Things or Common Things would work better.

That left Michael Sean Winters to settle the debate and he did so (in neo-Calvinist-friendly ways) by taking issue with Reno’s separation of life into different spheres:

There may be “other dimensions” as Reno notes, but surely, for the Christian, those other dimensions need to be related to “what matters most.” It was this dualism between the Catholic faith and Catholic morality that stalked Neuhaus’s writings and continues to afflict the journal he founded. This dualism not only colored Neuhaus’ judgment, but it kept much of his otherwise enjoyable controversial writings at a fairly superficial level. It also led him to overlook the failings of his own team, both in politics and in religion: His defense of the Iraq War and of Fr. Maciel were stains on Neuhaus’ intellectual project that deserve attention and explanation by those who champion him.

. . . Reno, too, puts his sacramental beliefs in one silo, and his moralizing in another, and never the two need challenge each other. That is not how Catholics think when we are thinking at our best.

Apparently, 2k thinking is a no-no for Roman Catholics as much as it is for neo-Calvinists. Everything belongs to God. Or the papacy has universal jurisdiction (which is a topic for discussion in its own right). Which makes it hard to justify solidarity with people of a different faith.

But if you limit that solidarity to the church and find all sorts of room for cooperation outside the church, problem solved. Why does that solution seem so impious?