Professor Jay Green’s thoughts about Covenant College and Hillsdale College have come and gone but his two articles do raise a couple of questions that may be worthy of further comment. The first has to do with the curriculum of a Christian college. The second has to do with that vexing question of Christ and culture, which runs to notions about transforming culture or integrating faith and learning. This post is about the former — curriculum — and it will read like a college catalogue because it relies on course descriptions from Covenant and Hillsdale to compare the religious dimension of a liberal arts college purporting to be Christian.

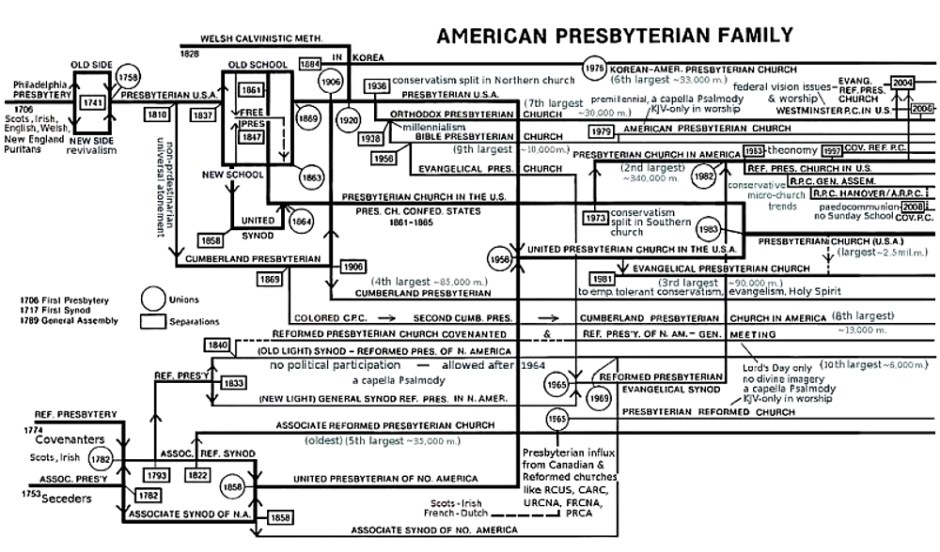

In his first post, professor Green distinguished between civilizational and confessional Christian colleges. Part of the difference stems from whether faculty actually need to affirm (believe) Christian statements of faith. At Covenant they do. For Green, Hillsdale is different because it “is a civilizational Christian college” in the sense of “acknowledging and honoring the strategically important role the faith played in laying the foundations of both Western Civilization and the American Founding.” He knows that many faculty at Hillsdale “also embrace Christianity in a confessional sense.” But because belief is not required at Hillsdale, “less time and attention are given to using Christian insights to critique things like Western Civilization and the American Founding.”

By the way, somewhere in here is a big point about ecclesiology and whether colleges should function like churches.

Not to be missed as well is an apparent assumption that Green does not develop — the idea that if you believe and teach Christianity you will critique Western Civilization and the American Founding. Does he mean to suggest that true believers will automatically be skeptical of the West and the United States? Or will they simply be willing to be critical, just as they would criticize Chinese or Islamic civilization and China and Indonesia? Or is he simply hinting that because Hillsdale is not sufficiently critical of the West and America — it is very political according to Green — the college loses its Christianness.

Whatever Green means about the relationship between Western civilization, the United States, and Christianity, his understanding of a confessional college leaves out what the apostle Paul included, namely, that those who preach the gospel out of envy or spite should be praised as long as they preach the gospel. That is, no matter the motives of the preacher or the faculty member, the content of what they preach or teach should be of first importance.

If catalogues are revealing, here is Covenant College’s description of basic courses in their core curriculum.

COR 100 The Christian Mind

This course is designed to introduce newly enrolled students to the general scope and distinctive emphases of a Covenant College education. The first portion of the course focuses on our calling in Christ and some of its implications for the task of being a student. The second portion introduces students to the Reformed tradition; and the third portion invites students to join with the faculty in addressing challenges that the tradition currently faces. 2 hours.

COR 225 Cultural Heritage of the West I

This course fosters cultural literacy by surveying important philosophical, theological, literary, scientific, and aesthetic ideas which have shaped Western culture. It begins with the earliest origins of Western culture in ancient Semitic (including Old Testament) and Greek cultures, then considers the transformation of these earlier influences successively in Roman culture, the rise of Christianity, the medieval synthesis of classical and Christian sources, and the Renaissance and Reformation. The course includes exposure to important works or primary sources, critiqued from a Christian perspective. 3 hours.

COR 226 Cultural Heritage of the West II

This course fosters cultural literacy by surveying important philosophical, theological, literary, scientific, and aesthetic ideas which have shaped Western culture. It considers the emergence of Modernism in the physical and social sciences from roots in the Renaissance and the Enlightenment as well as the effect of later reactions like Romanticism and Existentialism. The effect of these philosophical and scientific ideas on literature and other arts is also explored. The course includes exposure to important works or primary sources, critiqued from a Christian perspective. 3 hours.

Hillsdale in contrast spends a lot more time with the West’s cultural heritage though its catalogue says less about teaching from a “Christian perspective.” As part of the core curriculum students at Hillsdale take at least six courses — two in history, two in English, and two in Philosophy and Religion — that add up to 18 hours (ten more than Covenant). Here is what those courses are supposed to cover.

HST 104 The Western Heritage to 1600 3 hours The course will focus on the development of political cultures in Western Europe before 1600. It begins with a consideration of Mesopotamian and Hebrew civilizations and culminates in a survey of early modern Europe. The purpose of the course is to acquaint students with the historical roots of the Western heritage and, in particular, to explore the ways in which modern man is indebted to Greco-Roman culture and the Judeo-Christian tradition.

HST 105 The American Heritage 3 hours This course, a continuation of HST 104, will emphasize the history of “the American experiment of liberty under law.” It covers from the colonial heritage and the founding of the republic to the increasing involvement of the United States in a world of ideologies and war. Such themes as the constitutional tensions between liberty and order, opportunity in an enterprising society, changing ideas about the individual and equality, and the development of the ideal of global democracy will be examined. Attention will also be given to themes of continuity and comparison with the modern Western world, especially the direct Western influences (classical, Christian and English) on the American founding, the extent to which the regime was and is “revolutionary,” and the common Western experience of modernization.

ENG 104 Great Books in the Western Tradition: Ancient to Medieval 3 hours This course will introduce the student to representative Great Books of the Western World from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Selections may include the Bible and works by authors such as Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Vergil, Ovid, Augustine, and Dante. The writing content includes a variety of writing exercises that incorporate traditional compositional and rhetorical skills.

ENG 105 Great Books in the British and American Traditions 3 hours A continuation of English 104 but with a focus on Great Books in the British and American traditions. English authors may include Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Swift, Wordsworth, Dickens, Yeats, Eliot; American authors may include Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, Whitman, Dickinson, Twain, Frost, Hemingway, Faulkner, and O’Connor. The writing emphasis continues with a variety of writing exercises that incorporate traditional compositional and rhetorical skills.

PHL 105 The Western Philosophical Tradition 3 hours A general overview of the history of philosophical development in the West from its inception with the Pre-Socratic philosophers of ancient Greece to the 20th century Anglo-American and Continental traditions. The contributions of seminal thinkers and innovators such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, Locke, Hume, Kant, Mill, and Nietzsche are studied. Major works by these and other important philosophers are read, analyzed, and discussed with the aim of understanding what they argued for and against in regard to metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical issues. The course investigates to what extent they influenced their own and subsequent societies, how these philosophical systems create varying views of the world and human life, and how they address the perennial questions humans universally ask, existential questions such as, “Is there purpose and meaning in life?”; epistemological questions such as, “What are the limits of human knowledge?”; metaphysical questions such as, “What is the ultimate nature of the reality in which we live?”, “Is there life after death?”, “Are humans identical to their brains?”; and ethical questions such as, “What is the fundamental criterion of right and wrong human action?” In short, the course examines the main Western philosophical thinkers and traditions in an effort to understand what they have taught, why they have so taught, and how they have helped form and shape Western civilization.

REL 105 The Western Theological Tradition 3 hours A survey of the history of Western theology, analyzing and exploring the teachings of the various theological traditions that have influenced Western Civilization. Given the dominant influence of Christianity on Western culture and society over the past 2000 years, the course makes clear the theological teachings of the major Christian traditions that have prospered and played a significant role in shaping Western societies. The connections between theology and notions of proper community and individual life, theology’s influence on Western metaphysics and ethics, and the influence theology has had on the development of modern institutions and enterprises, such as modern science, are explored. In addition, the conceptual innovations about the nature of man and his abilities which theological disputes over the nature of God and Christ have provided are pointed out and discussed. Moreover, particular notions of the religious life and of the role of religion in life that have dominated Western thought on these matters are also explored. In short, students are instructed in the basic teachings of that faith that has dominated and, until recently, to a large extent directed the course of Western civilization in order to understand how religious belief informs self-understanding, provides a comprehensive view of reality, and, by instilling a vision of human life, its purpose and proper comportment, shapes the larger culture.

One aspect to notice, irrespective of the personal convictions of professors, Hillsdale’s curriculum is set up to present Christian context for the West and American government and culture. This instruction may be too friendly to Western culture and the United States, but it is very positive about Christianity. No specific confessional tradition claims to be at the center of Hillsdale’s Christian identity (though some faculty may try). But for Hillsdale to call itself a Christian college hardly looks like a bait and switch.

What is also striking is that Hillsdale delivers these courses on the West and America through specific academic departments. These courses are both in the core and at the beginning of a sequence of an academic major. Because they are not set apart in an interdisciplinary “Core” area which may be staffed by sociologists, English professors, historians, or musicians, Hillsdale’s “Core” curriculum is not set apart in a nebulous, required, general education or interdisciplinary part of the curriculum, something that students check off before getting to real courses in English, history, and philosophy. At Hillsdale, the core courses are the real courses (even if students still check boxes when taking them because of curricular requirements). This likely accounts for why Hillsdale has so many majors in English, history, and philosophy.

The exception to this pattern at Covenant are the required “Core” courses in Bible and Theology.

BIB 111 Old Testament Introduction

This course introduces the basic theological themes, chronological framework, and literary character of the Old Testament with a focus on Genesis – Kings. It aims to provide: 1) the foundations for theological interpretation of the Old Testament, giving special attention to the covenantal framework for redemptive history; and 2) an introduction to critical theories concerning the authorship, canonicity, integrity and dating of the documents. 3 hours.

BIB 142 New Testament Introduction

The course will deal with 1) questions of introduction (authorship, canon, inspiration, integrity of the documents, dating, etc); 2) beginning hermeneutics; 3) inter-testamental history as a background to the New Testament, as well as 4) a study of the historical framework of the New Testament as a whole, and key theological concepts. 3 hours.

BIB 277 Christian Doctrine I

A survey of the major doctrines of the Christian faith. First semester investigates the biblical data on Scripture, God, man and Christ. Second semester investigates the biblical data on the Holy Spirit, salvation, Church and last things. The Westminster Confession of Faith and Catechisms serve as guidelines and resources. 3 hours.

BIB 278 Christian Doctrine II

A survey of the major doctrines of the Christian faith. First semester investigates the biblical data on Scripture, God, man and Christ. Second semester investigates the biblical data on the Holy Spirit, salvation, Church and last things. The Westminster Confession of Faith and Catechisms serve as guidelines and resources. 3 hours.

These four courses give Covenant a leg up on Hillsdale, especially if you are a Presbyterian. Covenant requires two courses that survey study of Scripture, and two that summarize Christian doctrine. These arguably constitute the most confessional pieces of Covenant’s education. But because professor Green is more concerned with what faculty believe and profess, he spends little time in his published pieces on curriculum and academic departments.

What may be the most important difference between the two colleges is the way they conduct a liberal education. Both schools advertise themselves as liberal arts colleges. But at least at their websites, Hillsdale uses language that informed a long line of liberal arts colleges in the United States. Covenant’s statements are much less liberal education-inflected and bear some of the conviction of a Bible college where the Bible is pre-eminent and the arts and sciences are second string.

Consider this answer at Covenant to the FAQ, what makes Covenant different from other top-rate liberal arts colleges?

At Covenant, why you learn something is every bit as important as what you learn. Here, you will learn to see God in every facet of your life, and you will be personally taught by acclaimed professors who could teach virtually anywhere in the world and choose to be here.

At Hillsdale’s website the following describes the College’s commitment to a liberal arts core curriculum:

Liberal learning produces cultivated citizens with minds disciplined and furnished through wide and deep study of old books by wise authors. . . . It does so by leading forth students into a consideration of what has been called, “the best that has been thought and said.”

For what it’s worth, until the so-called fundamentalist controversy, Protestant denominational colleges (even Free Will Baptists) had no trouble offering a Christian and liberal education. Those colleges offered way more courses in the arts and sciences than they did in Bible and theology. Then when the mainline Protestant denominations started to go liberal (theologically) and dabbled with notions of God revealing himself as much through literature as through Scripture, fundamentalist-leaning Protestants turned to the Bible as the core of the college curriculum — first at Bible colleges and then at liberal arts schools like Wheaton, Gordon, and Westmont. How Hillsdale pulled off what it has — a return to the Protestant denominational Christian liberal arts college without being exclusively Protestant — is anyone’s guess.

If professor Green is a bit befuddled in pigeonholing Hillsdale College, he is not alone.