I’m not sure Jared Longshore has it right to talk about courageous Calvinism. That sounds a little too much like the cage-phase variety. But his observations about Old Calvinism in contrast with New Calvinism suggests Longshore may want more room to dissent from the niceness that dominates the Gospel Industrial Complex:

A cowardly Calvinist is an illogical thing. I don’t say that it is a thing that does not exist. Sadly, regrettably, shockingly, it does exist. But it shouldn’t. Before we get in too deep, no offense to the courageous non-Calvinist. My point is not to say that those who disagree with God’s sovereign decrees lack courage. Not at all. My point is rather to remedy what is all too common and downright inconsistent: the Calvinistic wimp. He is an enigma.

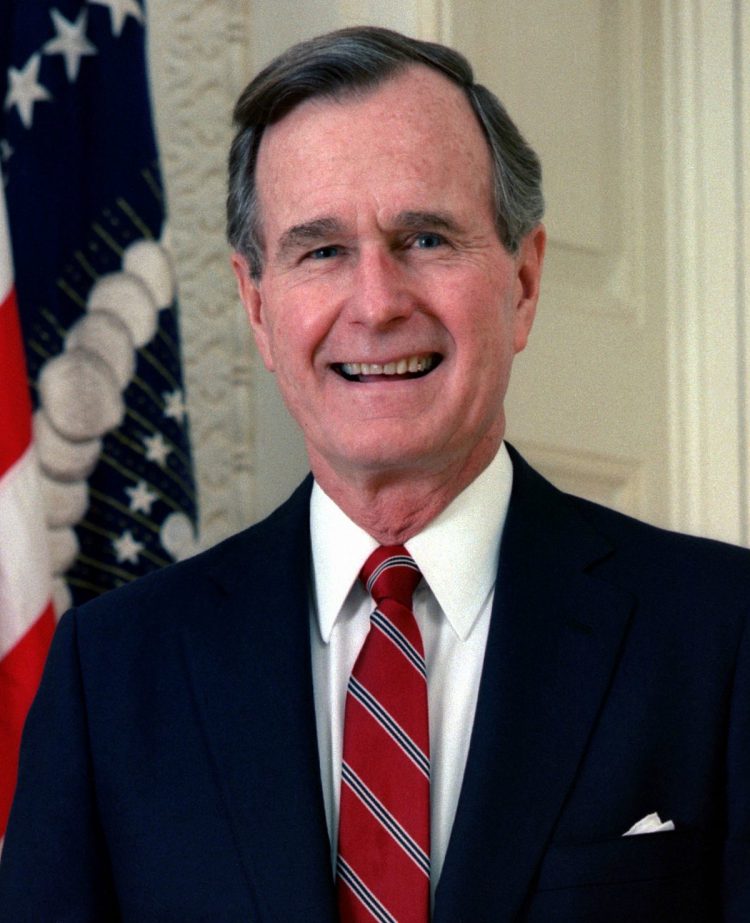

There may be some explanation for the man. I recall sitting down some years back with a leading Calvinist in the SBC. The spot was Louisville and the ocasion was T4G. I was a student at Southern Seminary quite certain that the third great awakening had struck. As I expressed my amazement over breakfast to this gentleman, amazement that so many young men we’re full of zeal for the glory of the sovereign God, his reply was a bit of a let down. “I’m just not sure how deep this whole thing is,” came the reply.

The words from a man who was a Calvinist when it wasn’t cool. A Calvinist when it wasn’t easy. A Calvinist when you actually had to examine the arguments of the other side and come to a settled and biblical position. So, perhaps the present quivering (and there is present quivering, we’re shaking like a freshly baked flan) is a symptom of the thin theology. If so, then let us go further up and further in.

We must get down deep in our bones that this courage is needed. Courage has always been required for those who would make God’s ways known among men. But there are certain times when that courage is especially necessary. Think Latimer and Ridley.

Why is courage needed today? Because if you open God’s Word and preach it plainly you’re going to be kicking over idols in every direction. You’re going to need courage because there has been a way to massage God’s Word, appealing to the secular mind, but that way seems to be just about all the way shut. You’re going to need courage because the exaltation of man has reached such a pitch, that, if you preach the truth about man’s fallen condition, you’re going to a be an outright bigot. And the colored lights and relevant worship set isn’t going to smooth things over any longer.

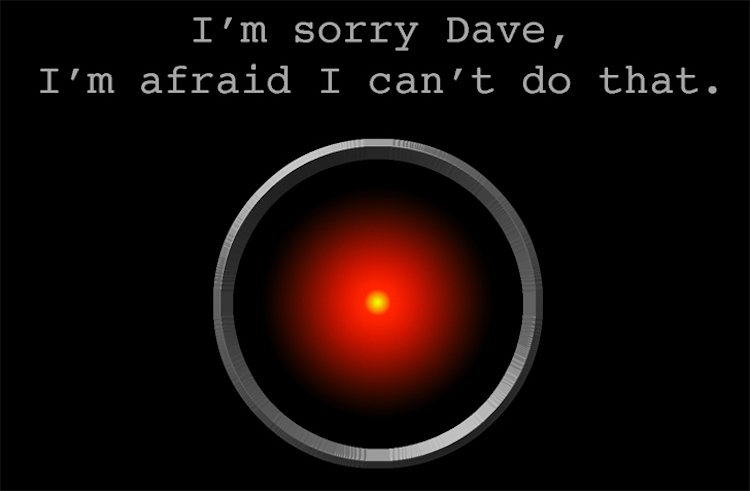

Again, I’m not fan of the everything-is-an-idol approach, but Longshore’s outlook is refreshing compared to just about anything about ministry at Gospel Coalition (like this):

Ortlinghaus: I think the primary opportunity is for gospel-centered churches to show that Jesus and his followers are not “haters.” When the national media portray Bible-following Christians as hateful and bigoted, we have an opportunity and mandate to love in the same way we see Jesus loving the woman at the well in the John 4—full of grace and truth. People want to see that our love is genuine (Rom. 12:9).

Buzzard: What God is using here is robustly orthodox, warmly loving Christians who enjoy close relationships with people wrestling through issues of sexuality—boldly, kindly pointing them to the authority of Jesus and his Scriptures over a long period of time.

Don’t accentuate the positive. Be straightforward.