Reformed Protestants 50 and up may have spent some of their reading hours with The Reformed Journal, a magazine of Dutch-American Calvinist provenance that came into existence as a forum for Christian Reformed Church progressives. I read it from my days as a seminary student until 1990 when it folded. I didn’t always agree with the politics or theology, but it was provocative and thoughtful.

Given the “progressive” character of the magazine, I should not have been surprised that TRJ’s regular contributors were slightly sympathetic but underwhelmed by J. Gresham Machen. That outlook bothered me because the deeper I went into the archives, the more impressed I was by the man who started Westminster Seminary and the OPC (with lots of help from others). In light of yesterday’s post with an excerpt from Machen’s testimony at his trial and with some reflections still fresh from the fall Presbyterian Scholars Conference (where several participants were experiencing the joy of post-PCUSA life but still not on board with Machen’s own version of that experience), I reproduce some high or low lights of TRJ takes on Machen.

First comes Rich Mouw’s argument that Machen’s departure actually hurt the cause of conservatism in the PCUSA (one echoed by George Marsden at the Wheaton conference):

Barbara Wheeler and I have argued much about the issues that threaten to divide us, but we share a strong commitment to continuing the conversation. She regularly makes her case for staying together by appealing to a high ecclesiology. The church, she insists, is not a voluntary arrangement that we can abandon just because we do not happen to like some of the other people in the group. God calls us into the church, and that means that God requires that we hang in there with one another even if that goes against our natural inclinations.

I agree with that formulation. And I sense that many of my fellow evangelicals in the PCUSA would also endorse it. The question that many evangelicals are asking these days, though, is whether God expects us to hang in there at all costs.

One of my reasons for wanting to see us stick together is that a Presbyterian split would be a serious setback for the cause that I care deeply about, namely the cause of Reformed orthodoxy. I spend a lot of time thinking about how people with my kind of theology, have acted in the past, and I am convinced that splits inevitably diminish the influence of the kind of orthodoxy that I cherish — for at least two reasons.

First, the denomination from which the dissidents depart is typically left without strong voices to defend orthodox. This is what happened in the early decades of the 20th century when J. Gresham Machen and his colleagues broke away from the northern Presbyterian church.

I know that this is not a very popular thing to say in this setting, but I happen to be a strong admirer of Machen. I think that he pretty much had things right on questions of biblical authority, the nature of Christ’s atoning work, and other key items on the theological agenda. But I have strong reservations about his ecclesiology and I regret that his views about the unity of the church led him to abandon mainline Presbyterianism. As long as he remained within the northern church, he had a forum for demonstrating to liberals that Calvinist orthodoxy could be articulated with intellectual rigor. When he and his friends departed, this kind of witness departed with them.

The evangelicals who stayed on in the northern church generally did so because they were not as polemical as the Machen group; they were also not nearly as inclined as the Machenites to engage in sustained theological discussion. This meant that the quality of theological argumentation in mainline Presbyterianism suffered for several decades — some would even say up to our present time.

Not to let facts get in the way here, but Mouw would do well to remember that the PCUSA brought Machen to trial and excommunicated him. Yesterday’s post shows that Machen was not eager to flee even if it would have been a lot more pleasant. Whether his actions were legitimate or constitutional is another question. But he asked about the constitutionality of PCUSA actions and that didn’t endear him to the people who stayed. In fact, they tried him for having the temerity to question the soundness of the Board of Foreign Missions — as if that’s never happened — and the administrative fiats that condemned dissent.

I too wonder if Mouw considers that from 1869 until 1920 the PCUSA became infected by the social gospel and Protestant ecumenism. During that very same time Princeton Seminary as the voice of Reformed orthodoxy in the northern church was still dominated by conservatives. What happened during the years when Princeton kept alive the theology that Mouw values? Princeton and it’s orthodoxy became marginal and then a nuisance — hence the reorganization of Princeton Seminary in 1929. The idea that had Machen stayed conservatives would have done better is naive and ignores what actually happened before Machen “left.” Plus, what kind of high ecclesiology settles for articulating “Calvinist orthodoxy with intellectual rigor”?

George Marsden and Mark Noll regularly wrote for TRJ and again the returns on Machen were not always positive. First, Marsden:

Both at the time and since critics of Machen have suggested that there was something peculiar about him. Most often mentioned are that Machen remained a bachelor and his very close relationship to his mother until her death in 1931. Neither of these traits, however, was particularly unusual in the Victorian era, which certainly set many of Machen’s social standards.

More to the point is that he does seem to have had a flaring temper and a propensity to make strong remarks about individuals with whom he disagreed. One striking instance is from 1913 when Machen had an intense two-hour argument with B. B. Warfield over campus policy, after which Machen wrote to his mother that Warfield, whom he normally admired immensely, was “himself, despite some very good qualities, a very heartless, selfish, domineering sort of man.” You can imagine that, if someone says things like this about one’s friends, that it might be easy to make enemies. Machen does not seem to have had a great ability to separate people from issues, and this certainly added to the tensions on the small seminary faculty. Clearly he was someone whom people either loved or hated. His students disciples were charmed by him and always spoke of his warmth and gentlemanliness. His opponents found him impossible, and it is a fair question to ask whether, despite the serious issues, things might have gone differently with a different personality involved.

This observation continues to baffle me, as if people do not distinguish public from private statements. Maybe we are only learning that lesson after Donald Trump, but historians generally know that in the archives you find people saying all sorts of things that they wouldn’t say in public. In private we blow off steam, unless we are all walking John Piper’s and sanctified all the way down. I also don’t understand why Marsden starts his sentence on Machen’s personality with the man’s opponents found him impossible. Hello. The feeling was mutual. But Machen as a sanctified believer was supposed to find his adversaries hedonistically delightful?

And finally, Mark Noll’s estimate on the fiftieth anniversary of Machen’s death:

By reading controversies within Princeton Seminary, Presbyterian missions, and eventually the Presbyterian denomination as battles between two separate religions, “Christianity and Liberalism,” Machen undermined the effectiveness of those Reformed and evangelical individuals who chose to remain at Princeton Seminary, with the Presbyterian mission board, and in the Northern Presbyterian Church. By committing himself so strongly to theological and ecclesiastical combat, Machen left successors who were ill-equipped to deal with the more practical matters of evangelism, social outreach, and devotional nurture. By pursuing the virtues of confessional integrity, he opened the door to sectarian pettiness.

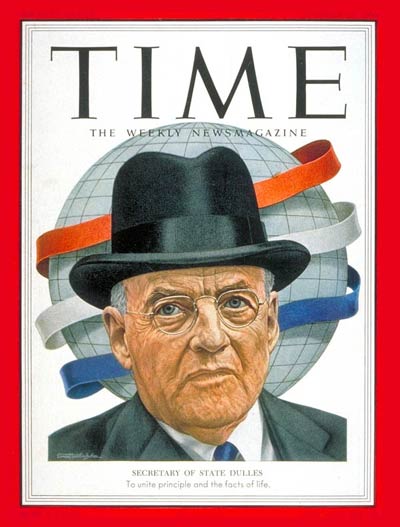

No real sense here that blaming the victim is a potential downside of such an interpretation. The perspective seemed so often in TRJ to be that Machen was a man on a mission and looking for a controversy. The bureaucrats and seminary administrators were innocent. (Yes, the lawyer who defended modernists in the 1920s, John Foster Dulles, became the Secretary of State who crafted the Eisenhower administration’s Cold War policies — the very administration that the founding editors of TRJ questioned.) The Presbyterian hierarchy simply responded — with a hammer, mind you — to Machen’s provocations. That could have been the case but no one argued that. They largely reduced Machen to a cantankerous figure who got what most of us would expect if we rock the boat the way he did.

And now in hindsight I wonder what these same men would think of Abraham Kuyper who was also part of a church that came out of the Netherlands’ state church. Didn’t Kuyper’s GKN (Reformed Churches of the Netherlands) make it a lot harder for conservatives who stayed in the NHK (Dutch Reformed Church)? And didn’t Kuyper’s Free University make life more complicated for orthodox theologians who remained at Leiden or Utrecht? (In other words, why wouldn’t it be possible to imagine Machen akin to Kuyper? Why doesn’t the Kuyper glow trickle down to Machen? Because Kuyper became Prime Minister and Machen merely president of the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions?)

And what of John Calvin? Was he wrong to leave France? Did he leave Huguenots in the lurch? Was the Roman Catholic Church worse off without Calvin’s ministry and theological reflection? Or does the mind boggle at the questions you need to start asking other historical figures when you become so demanding of a figure of which you disapprove?