The incident in Charlottesville gave Jemar Tisby another chance in the op-ed section of the Washington Post. No one could disagree with Mr. Tisby’s estimate that this protest was an instance of white supremacy or that it is ugly and a threat to public order and the rule of law.

But I do wonder if Mr. Tisby lost his nerve when speaking to a national audience. For instance, in an earlier post last spring about another incident in Charlottesville, he wrote this at his own blog:

As much as city leaders sought to gain support for removing Confederate monuments and symbols, they never had complete consensus. Officials in New Orleans kept the date and time of the monument removals secret for fear of reprisals from their opponents. The Confederate flag came down in South Carolina in the middle of vocal defiance of the decision. Yet come down they did.

In the church as in the world, the time is always right to do right. Racism is sin. Leaders should not take a gradual approach to killing racism just like they should not take a gradual approach to killing any other sin. Nor should they think it necessary to build a consensus to combat this sin. True leadership initiates righteous changes even when they are unpopular with those being led.

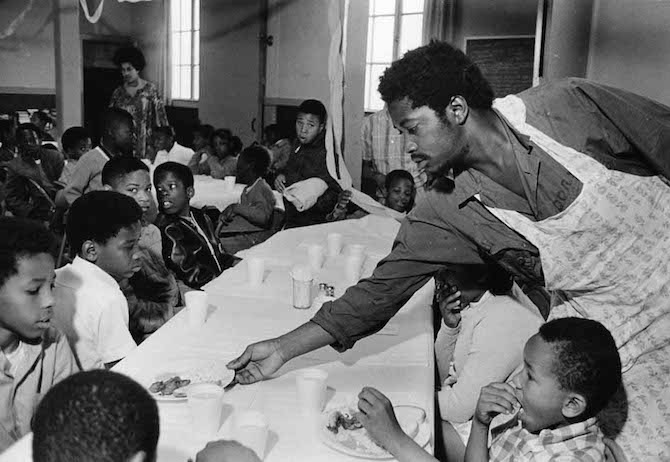

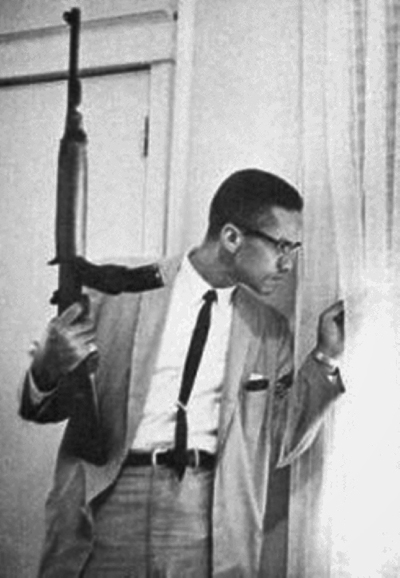

That is the kind of radicalism that Charles Finney took to Oberlin College. If it’s sin, you break with it immediately. Any delay is even more sin. It is even in the ballpark of the sort of radicalism that Malcolm X promoted. If you have a system that is so brutally and obviously bad, you need to blow it up or leave it. That was part of X’s appeal — he advocated black nationalism and black separatism, and given the nature of Jim Crow and police brutality, you could understand why.

But at the Post, Mr. Tisby backed away from that sort of radicalism and admitted that we will always have racists with us:

Let’s also be clear that we can’t really end white supremacy. In the Christian view, racism is a sin, and sin cannot be completely eradicated on this side of eternity. But we are called to fight against sin in all its forms, so we should expect positive change in our churches and society at large as we fight against it.

So how do we fight white supremacy without taking Malcolm X’s path? Cue Joni Eareckson Tada:

1. Admit the American church was built on white supremacy.

From the Colonial era to the present day, white churches have helped build a society that privileges whiteness and denigrates blackness. In light of the white church’s involvement in creating and maintaining white supremacy, white pastors can presume that their churches are already part of the problem, intentionally or not.

2. Confess and repent of past sins.

Many congregations were formed in a fit of “white flight” from cities. Many Christian schools, particularly in the South, were explicitly created to preserve racial segregation in an era of court-ordered desegregation. Christians and church leaders must ask themselves how much they have acknowledged their own history. Have they gone through their church records and rulings to tell the full story of how their church, community, or denomination has cooperated with white supremacy? A failure to face white supremacy in the past will lead to a failure to confront it in the present.

3. Commit to responding to white supremacy with the vigor that the problem requires.

When we examine the history of race and the American church, the story is often worse than we expect. The church hasn’t simply gone along with white supremacy — it has assembled and established it. If white Christians have historically been so intentional about building up barriers between the races, then they will have to be just as intentional to bring them down.

4.Listen to black people.

We’ve been saying all along that a Charlottesville could easily happen. For years, the alt-right and white nationalists have employed the Bible to justify their racism, in public online. But many white Christians have never heard of the alt-right, much less been equipped to filter their messages biblically. We kept trying to tell them that this obsession with the Confederacy and its cultural artifacts sabotaged efforts at racial unity.

In addition to the fourth point, which is an implicit pitch for Mr. Tisby’s podcast, this is advice right out of a w-w play book — take every thought captive. It’s all about thinking and making personal resolutions.

But imagine telling that to Germans living in the 1930s under the tyranny of National Socialism. When evil is so institutionalized and so oppressive, as Mr. Tisby has long argued, do you simply commit to do things differently? Or do you actually think that Malcolm X had a point? You overturn the system or get out and form a separate nation? Mr. Tisby’s recommendations strike me as the equivalent of what I hear about climate change. What do I do? I feel badly and commit to do better, even when the entire food distribution system and development of town life in the U.S. is predicated on the use of fossil fuel.

In other words, Mr. Tisby’s recommendations are sort of like saying don’t trust the system but don’t forget to work with the system. Glenn Greenwald spotted the flaw in this logic when he went after those who complained about the ACLU’s defense of Charlottesville’s white supremacists’ rights to assembly and free speech:

. . . the contradiction embedded in this anti-free-speech advocacy is so glaring. For many of those attacking the ACLU here, it is a staple of their worldview that the U.S. is a racist and fascist country and that those who control the government are right-wing authoritarians. There is substantial validity to that view.

Why, then, would people who believe that simultaneously want to vest in these same fascism-supporting authorities the power to ban and outlaw ideas they dislike? Why would you possibly think that the List of Prohibited Ideas will end up including the views you hate rather than the views you support? Most levers of state power are now controlled by the Republican Party, while many Democrats have also advocated the criminalization of left-wing views. Why would you trust those officials to suppress free speech in ways that you find just and noble, rather than oppressive?

Greenwald’s question is one I’d like to hear Mr. Tisby answer. If the United States was founded by racists, prolonged its racism through slavery and Jim Crow, and now continues that racism in policies of mass incarceration executed by Republicans — and there is validity to this understanding of U.S. history, I’m not saying it’s wrong — then why continue the United States? Why obey the laws of the U.S.? Why submit to police? Why not instead rebel and bring down such an oppressive regime?

Is it because the next regime will also be a sinful one that has its own oppressive bugs (not features)? In which case, is the argument that sin is structural really self-defeating? It certainly gets attention and inspires outrage. It also gives you a platform that will never go away because you’ll always have a system to oppose. But at a certain point, the protest looks like only pious advice unless it counters the unjust structure not with a commitment to do better but an alternative structure.