From the Archives: Nicotine Theological Journal (Spring, 2009)

Making Sense of the PCA

I have been a minister of the Presbyterian Church in America from its founding. I attended the Convocation of Sessions, the Advisory Convention, and the first General Assembly in 1973. I have not been what one would call “a player” over the past 30 years, but I have been “involved.” I was one of the early Reformed University Ministry (RUM) campus ministers, had a full term as a member of the Committee on Mission to the World, and served on the Creation Study Committee. I edited work for children’s curriculum for Great Commission Publications. I have traveled to Japan, Philippines, Ukraine, France, and Turkey in connection with MTW mission work.

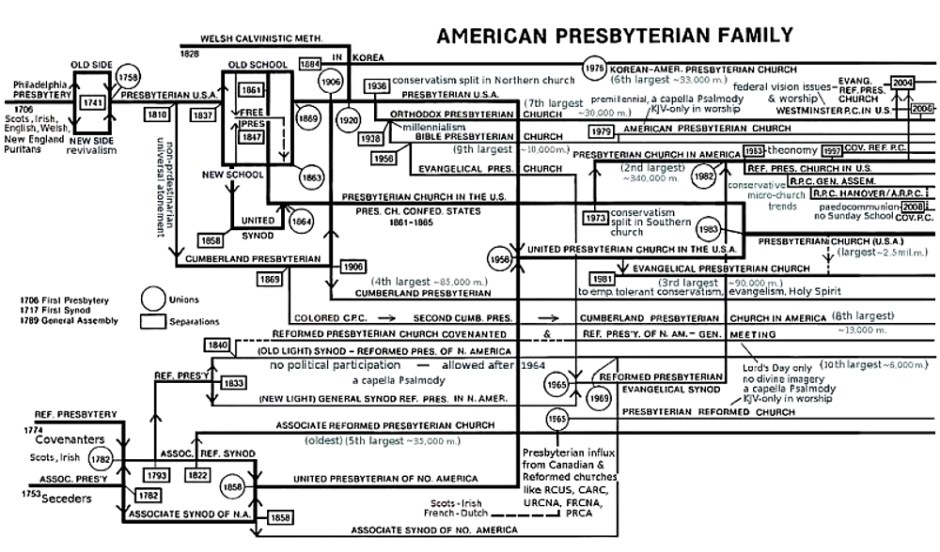

As our denomination has experienced recent tensions about confessional subscription, our mission, and worship, I have struggled to understand how we got here. My working hypothesis is that the PCA is a majority New Side/New School Presbyterian Church, with a substantial minority that is either New Side/Old School or Old Side/Old School.

The differences between the Old and New Side Presbyterians focused primarily on their differing views of revivals. The New Side believed the revivals or George Whitefield, which first disturbed and then converted sinners within and without the church and awakened and stirred to holiness and action true believers, had biblical precedents. Itinerant ordained and non-ordained speakers were often the instruments of revival. Religious experience was intensely personal and greatly concerned with whether or not one had been genuinely converted.

Old Siders had a higher view of the church as an institution, more confidence in the work of settled, ordained ministers carrying out the ordinary ministry of word and sacrament, and a greater emphasis on corporate religious life. Tensions over subscription pushed New Siders toward a looser view, with the Old Side arguing for strictness. Neither side was monolithic.

If the First Great Awakening balkanized the Old and New Sides, the Second Great Awakening returned the favor for the Old and New School Presbyterians. Despite this similarity, the major issue in the nineteenth century was not revivalism but confessionalism. Old Schoolers had differing appraisals of the earlier awakenings, but they shared a growing unease about the Second Great Awakening with its Arminian theology and its new measures.

In order to defend the theology of the Second Awakening New Schoolers had to take a broad view of the Westminster Standards and a much weaker view of what was involved in an officer’s ordination vows. The New School strongly favored mission over theology while the Old School held that theology defines and directs mission. Because of its emphasis on mission the New School favored working with parachurch societies to accomplish evangelism and missions, while the Old School believed the church alone was responsible for spreading the gospel and building up the saints. Part of the mission-orientation of the New School was its commitment to engage social issues, such as slavery and temperance, as part of an effort to Christianize America. Old Schoolers countered with the spirituality of the church. Not surprisingly, the New School had a low view of the church while the Old School maintained and defended jure divino Presbyterianism.

How does this explain the PCA? In my view, the majority of the PCA consists of three groups all of which share a New Side/New School orientation: the Columbia Seminary founding generation, the Reformed Presbyterian Church, Evangelical Synod (RPCES) influx, and the rising leadership consisting primarily of large urban/metropolitan church pastors and denominational executives.

Most of the founders of the PCA had been educated at the most conservative of the PCUS (Southern Presbyterian) seminaries in the 1950s and 1960s. While Columbia could trace her heritage all the way back to Thornwell, the most eloquent Southern Old School voice, little remained of Thornwell’s influence (William Childs Robinson being the exception) by the time PCA leaders received their training at Columbia. Students were considerably more conservative than the faculty at Columbia, but they were never much exposed to the old Confessional orthodoxy of the Southern Church. They believed in the Bible, in “the fundamentals,” in the gospel, and in evangelism and missions. They took their ordination vows with sincerity but they did not consider how those vows bound them to the Westminster Confession. In fact, many of these brothers were influenced by teachings that were inconsistent with Calvinism. I think of semi-Pelagianian, Invitation System revivalism, dispensationalism, and perfectionism. In addition, they were suspicious of church institutions and authority (having witnessed and experienced the corruption and abuse of the mainline Southern church) and were eager to cooperate with any evangelicals to win the world for Christ, maybe even “in this generation.”

It was not clear at the time of Joining and Receiving (J&R) in 1982 what the impact of the influx of the RPCES would be, but time has proved that it broadened and strengthened the New Side/New School segment of the PCA. The RPCES was the result of the union of the dwindling Reformed Presbyterian Church in North America, General Synod (a “new light” break-off from the Covenanters), and the larger Evangelical Presbyterian Church (from the McIntire wing of 1936.) Although RPCES was more Reformed and Presbyterian than McIntire’s Bible Presbyterians, its roots remained New School, and, though there was some indication the RPCES might move toward Princeton Old School positions, this did not materialize. The RPCES was and remains New Side/New School and so injected into the PCA another dose of New Side/New Schoolism.

What then of the rising leadership? The one word, which best catches the outlook and agenda of this group, consisting primarily of large urban pastors and denominational executives, is “missional.” In the New Side/New School tradition, mission is the church’s defining characteristic and responsible for its vitality and unity.

This “missional” orientation has been notably evident in recent worship services at the General Assembly. Mission requires us to rethink what it means to be church and to sit loose on doctrinal formulations, on polity issues, on how we worship, and on what the nature of the mission of the church is, so that as we understand more of this “post-everything” culture and figure out how to respond, we can make the necessary adjustments to further the church’s mission. This is decidedly the New Side/New School outlook, dressed in new clothes, but with the substance of the body unchanged.

This represents the majority of the PCA’ teaching and ruling elders. A majority holds to the New Side/New School type of Presbyterianism. At the same time a substantial minority in our church, with Old and New Side proclivities, holds to Old School Presbyterianism. This means that issues of doctrine, polity, subscription, worship, and mission remain live ones for the foreseeable future. The soul of the church is at stake for both the majority and minority.

William H. Smith is pastor of Covenant Presbyterian Church (PCA) in Louisville, Mississippi.