Oliver O’Donovan, a favorite political theologian of many Protestants who may not be comfortable with Stanley Hauerwas’ anti-establishmentarian outlook but also want an alternative to the Religious Right (and won’t even consider the spirituality of the church), has a review of Abraham Kuyper and the returns are not good:

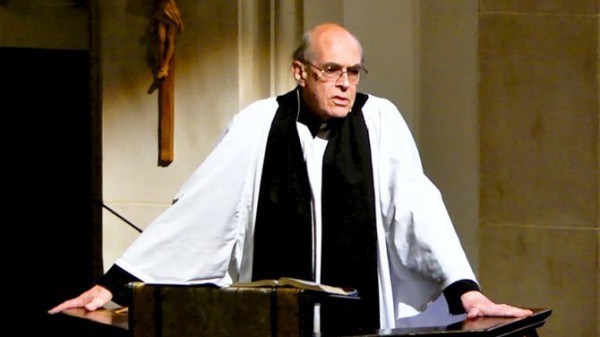

Kuyper’s manner is self-consciously didactic. He seems to speak from a pulpit with a Bible in hand and a congregation to wag a finger at. He luxuriates in general social observations rounded up with peremptorily declared conclusions, which can sometimes seem very arbitrary. Exaggerated oppositions, over-compartmentalized classifications, silence on what others are thinking or saying (except where they can be dismissed with a wave of the hand)—these are the weaknesses that belong to his communicative strategy. And most trying of all is his confidence that whatever he says is proved at the bar of Scripture, though what he finds in a text and what he makes of a text are rarely distinguishable. The paths of argument are circuitous, and what appears to be firmly settled at one point may turn out to be surprisingly open to qualification later. All that, if we will read Kuyper, we must bear with patience. But if we will let him lead us by the paths of his own choosing, and alert us to the spiritual and cultural challenges he discerns, we shall find ourselves inducted into a vision of the world that deeply impressed its first readers. The list of interesting and distinguished twentieth-century figures who confessed a debt to Kuyper’s influence speaks for itself.

Kooky but influential. Isn’t that true of Donald Trump? This may explain why Jamie Smith spends much more time interacting with O’Dovovan than Kuyper.

And for those Kuyperians who look down on Old School Presbyterianism, O’Donovan’s estimate of Kuyper is even less kind — though it suggests spirituality of the church thinkers may need to spend more time with the former Dutch Prime Minister:

While insisting that Christ’s kingship must not be spiritualized, Kuyper says that it must not be politicized, either. For while his dominion has everything to do with public cultural endeavor in science, agriculture, poetry, education, and music, it has nothing to do with civil government (paradoxically the sphere of Kuyper’s own public endeavors!). In this way, Kuyper saves the face of a Reformed tradition that assigns the civil state to God the Father’s care, the Church to the care of the Son.

Is not the idea of a heavenly “king” without political authority a bad case of “spiritualizing” (a harsher term might be “mythicizing”)? It raises problems enough for the traditional political analogies, on which much of Kuyper’s rhetoric depends. It deprives him of the use of some of the most fruitful biblical material for reflecting on authority, that of the Hebrew kings. It raises problems for his own programmatic boast that there is “not a square inch . . . over which Christ does not say ‘Mine!’” And it raises problems for Christian politics itself, ambiguously placed among the spheres of Christian service.

And that is exactly where O’Donovan needs to pay attention to Kuyper and those outside ecclesiastical establishments like the Church of England. The Hebrew kings were good — well not really — for their time but when Jesus came the Hebrew monarchy took a different form, one in which the Son of David could say with a straight face, “my kingdom is not of this world.” At the same time, the Gospels present lots of material for thinking about political authority in relation to Christ — how he interacts with government officials, with Jewish authorities, how he answers questions about political rule or instructs his disciples (like telling Peter, “put the sword away”), how he went into exile during the slaughter of the innocents, how he submitted to Roman execution, how he claims all authority in the Great Commission.

Lots of biblical material there but I am betting it does not add up to Christendom, whether the Roman or Anglican version.