He had a keen sense of pretense, that is, when people were trying to be something more important than they really wore. Mencken was especially astute at detecting pretense in politics. Would World War I make the world safe for democracy or be the war to end wars? Seriously? Would a given federal program or policy eliminate crime or poverty? What kind of gullibility do you need to believe that?

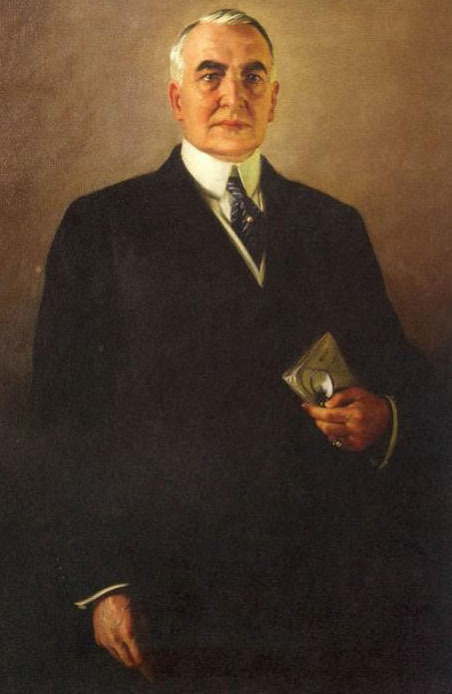

When it came to spotting where inspiration left reason behind in political speeches, Mencken was relentless. Consider his take down of Warren G. Harding:

On the question of the logical content of Dr. Harding’s harangue of last Friday I do not presume to have views. The matter has been debated at great length by the editorial writers of the Republic, all of them experts in logic; moreover, I confess to being prejudiced. When a man arises publicly to argue that the United States entered the late war because of a “concern for preserved civilization,” I can only snicker in a superior way and wonder why he isn’t holding down the chair of history in some American university. When he says that the United States has “never sought territorial aggrandizement through force,” the snicker arises to the virulence of a chuckle, and I turn to the first volume of General Grant’s memoirs. And when, gaining momentum, he gravely informs the boobery that “ours is a constitutional freedom where the popular will is supreme, and minorities are sacredly protected,” then I abandon myself to a mirth that transcends, perhaps, the seemly, and send picture postcards of A. Mitchell Palmer and the Atlanta Penitentiary to all of my enemies who happen to be Socialists.

But when it comes to the style of a great man’s discourse, I can speak with a great deal less prejudice, and maybe with somewhat more competence, for I have earned most of my livelihood for twenty years past by translating the bad English of a multitude of authors into measurably better English. Thus qualified professionally, I rise to pay my small tribute to Dr. Harding. Setting aside a college professor or two and half a dozen dipsomaniacal newspaper reporters, he takes the first place in my Valhalla of literati. That is to say, he writes the worst English I have ever encountered. It reminds me of a string of wet sponges; it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean-soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights. It is so bad that a sort of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm (I was about to write abscess!) of pish, and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of posh. It is rumble and bumble. It is flap and doodle. It is balder and dash.

The Bible tells believers not to put trust in princes. So does Mencken. Christians should appreciate his help.