Maybe I am not philosophically inclined. Maybe I am too American and hence of a pragmatic frame of mind. Maybe I like cats too much. But if I owned a gun I would reach for it whenever theologians and pastors enter into realms speculative.

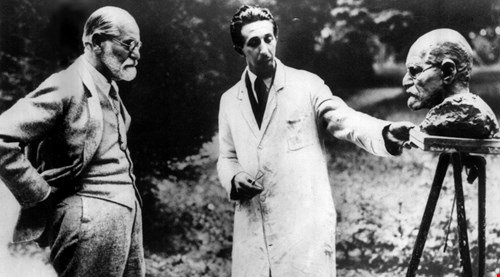

One of the areas of study I teach most prone to speculation is the way that theologians and philosophers relied on faculty psychology as if the will, motivation, choice, and affections are as easy to spot as the genitalia of an unborn child through a sonogram, or as if Sigmund Freud’s popularity owed to the ease of curing psychological woes.

Here’s an example of the murky realm surrounding faculty psychology upon which Puritans spilled so much ink:

Edwards’s psychology assimilated affections and will, motive and choice. The will (choice) was as the greatest apparent good (motive). Motive was choice or volition. Action followed choice, in appropriate circumstances, because God as the efficient cause, although human motive or volition might occasion action. (Bruce Kuklick, Churchmen and Philosophers, 100)

But get this. Not everyone agreed with Edwards, like Nathaniel Taylor:

Taylor’s psychology differed. For him, motives were distinct from choice or volition, and volition caused action. Taylor’s psychology was tripartite, consisting of the affections, will, and understanding; Edwards’s was dual, consisting of the affections (emotions/will) and understanding. (Kuklick, 100)

Is anyone willing to stake salvation on any of these — wait for it — speculations? Or is this plain as day?

But for Puritans, such speculations were part and parcel of the self-reflection that secured assurance of salvation:

Religious experience — in particular, conversion — involved a process which engaged all the faculties of the soul, but which was most deeply rooted in the affections. And the experience, whether in conversion or in the worship that followed, was one in which the believer acted, and was not just acted upon, in virtually every phase. . . . In the early stages of the process of conversion the Holy Spirit drew the chose to Christ, given that the man affected had been elected to receive what [Richard] Mather called the grace of faith (a phrase with Thomistic implications). Mather agreed with most Puritan divines that a man who had been consigned to Hell might experience the same feelings that gripped a saint in the first steps of conversion. . . . At this point the sinner becomes aware of his helplessness; and emptied of his pride he is ready for the knowledge of Christ, a knowledge that the law cannot convey. Comprehending this knowledge is the responsibility of reason, or understanding, but not exclusively so if the whole soul is to be renewed. . . . The knowledge must “affect” them in such a way that they approve and love it. At this point with all the faculties deeply informed, and moved, the grace of faith is infused by the Lord into the soul. (Robert Middlekauff, The Mathers, 64-65)

And your scriptural text is?

I understand the great debt that modern day psychology owes to Puritan speculations about the inner gears of the soul. But is that where Reformed Protestants with the Puritan fetish really want the legacy of Puritanism to go? Can John Piper generate enough earnestness to make any of this comprehensible?