Kevin DeYoung deserves praise for defending John Witherspoon and the American revisions to the Westminster Standards. Some of us were doing this back in the day when the Federal Vision was echoing the theonomists. But the post-liberal turn among Protestant Christian nationalists and Roman Catholic integralists has increased the need for a defense of the American revisions and their harmonization of Reformed teaching and the American Founding (republicanism, constitutional federalism, religious liberty).

The post-liberal Protestants at American Reformer have not welcomed DeYoung’s understanding of American Presbyterians’ revisions of Westminster. Some argue for continuity between the original Westminster Confession and the 1789 revision. Others go farther and assert that even the American Revisions require an affirmation of a religious establishment.

What is largely missing from the critics of DeYoung is attention to the Covenanters (or Reformed Presbyterians) whose views are similar to theirs — the American Founding is seriously flawed — and whose understanding of the civil magistrate was the dominant view among Presbyterians at the time of the Westminster Assembly. DeYoung’s first article does in fact address the corner into which the Covenanters had painted Presbyterians. He wrote:

In 1707, the Act of Union brought together England and Scotland under the name of Great Britain. Many Presbyterians opposed the union as inconsistent with the principles celebrated in the National Covenant (1638) and the Solemn League and Covenant (1643) and as undermining the Revolution Settlement (1690) which restored Presbyterian government to the Established Church in Scotland.

DeYoung later adds the change in Presbyterianism that transpired after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He uses John Coffey, the leading scholar of Samuel Rutherford, to describe that change:

“With the exception of the Reformed Presbyterian Covenanters and some Seceders, eighteenth-century Presbyterians found ways of distancing themselves from the Westminster Assembly’s teaching on the coercive powers of the godly magistrate in matters of religion…. In every part of the English-speaking world, Lockean ideas of religious liberty looked increasingly attractive to Presbyterians who feared Anglican hegemony or saw little prospect of becoming the dominant majority.”

Zachary Garris says the Covenanters are not in the mainstream — that’s true for America today. But it was not true for the people who wrote the Westminster Confession — Presbyterians, Puritans, and Independents from England and Scotland. In fact, Scotland’s covenants with her kings (the Stuarts) who became the kings of England as well set the standard for political theology at the Westminster Assembly. Here’s why:

The Scottish Reformation gained a victory in 1581 with King’s Confession of 1581 by which James VI (later James I of England) vowed, with Parliament, the Kirk, and the people to uphold and defend the true religion (Reformed) and oppose the false religion (Roman Catholicism).

In 1638, this time with Charles I (James’ son) imposing the Book of Common Prayer on the Scottish Kirk, Parliament, the Kirk, and the people ratified the National Covenant. The expectation was for Charles to pledge his allegiance to this covenant because of the original (King’s) covenant with his father.

Soon after the National Covenant, Scottish military went to war with Charles — you guessed it, he didn’t take the vow — in the first of two “Bishop’s Wars” (1639-1640). The Scots’ covenants and war with Charles were the trial run for the English Parliament’s civil war with the king (1642-1649), the same Parliament that called for an overhaul of the Church of England and gave the responsibility to the Westminster Assembly. The English Parliament needed military help from the Scots who in turn gave it conditioned on Parliament’s ratifying an international covenant — the Solemn League and Covenant (1643). Although that covenant had different legal justification from the Scots’ National Covenant, the Solemn League and Covenant extended to England and Wales the same cooperation among the civil government, the church, and the people to uphold the true faith (and oppose the false religion of Rome) in Scotland.

Covenanting and national covenants were hardly peripheral to seventeenth-century Presbyterianism of the Westminster Confession. Covenanting likely explains one of the oddest chapters in the Confession of Faith — chapter 22 on Oaths and Vows. (If you are in a covenanting mind set, you may likely clarify the theological import of promises taken in the civil and ecclesiastical realms.)

If you wonder where Christian Nationalism among Presbyterians comes from, you may well want to look to the Covenanters.

This covenanting backdrop is especially important for understanding the American revision of the Westminster Confession. By the 1780s, the covenanting position was not part of the Presbyterians who comprised the first General Assembly of the PCUSA. That is because the Covenanters had formed their own communion, the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America. Which is also to say that everyone in the Presbyterian world (England, Scotland, Ireland, the United States, and eventually Canada) gave up on covenants with Scottish monarchs. The lone exceptions were the Covenanters and certain sectors of the Seceders (Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church).

Why the critics of Dr. DeYoung do not resonate with or follow the Covenanters is a mystery. So is their unwillingness to acknowledge that they desire a relationship between the church and civil magistrate like the ones the Covenanters briefly had between 1638 and 1650. There is also a good chance that the American Reformers who pounced on Dr. DeYoung agree with Covenanter assessments of the American Founding. This is the Covenanter understanding of the U.S. Constitution (which puts a dent in American patriotism):

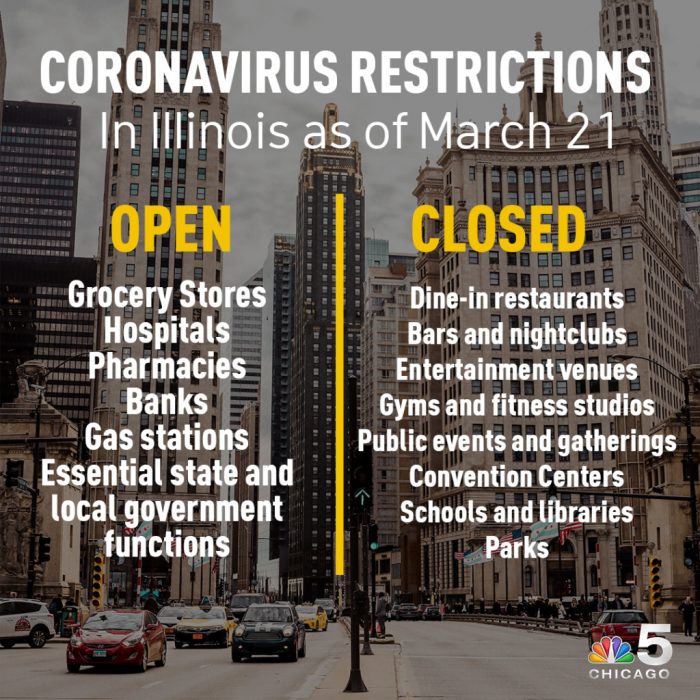

There are moral evils essential to the constitution of the United States, which render it necessary to refuse allegiance to the whole system. In this remarkable instrument, there is contained no acknowledgment of the being or authority of God —there is no acknowledgment of the Christian religion, or professed submission to the kingdom of Messiah. It gives support to the enemies of the Redeemer, and admits to its honours and emoluments Jews, Mahometans, deists, and atheists—It establishes that system of robbery, by which men are held in slavery, despoiled of liberty, and property, and protection. It violates the principles of representation, by bestowing upon the domesticity rant who holds hundreds of his fellow creatures in bondage, an influence in making laws for freemen proportioned to the number of his own slaves. This constitution is, notwithstanding its numerous excellencies, in many instances inconsistent, oppressive, and impious.

Since the adoption of the constitution in the year 1789, the members of the Reformed Presbyterian Church have maintained a constant Testimony against these evils. They have refused to serve in any office which implies an approbation of the constitution, or which is placed under the direction of an immoral law. They have abstained from giving their votes at elections for legislators or officers who must be qualified to act by an oath of allegiance to this immoral system. They could not themselves consistently swear allegiance to that government, in the constitution of which there is contained so much immorality. (Reformation Principles Exhibited, 1807)

The differences between the PCUSA and the RPCNA reflect the changes that occurred throughout the Presbyterian world once most communions abandoned Scotland’s National Covenants. Locke made a lot more sense of British society for accommodating religious diversity than insisting on promises Stuart monarchs had made to Scotland and England. And that difference was an important factor in Witherspoon’s role in revising the Westminster Confession and Catechisms.

Dr. RevKev understands that both the moderates and the evangelicals in the Church of Scotland, as well as the Old Side and New Side Presbyterians in America had no sympathy for Scotland’s covenants. They had move on.

Critics of Dr. RevKev may refuse to be lumped with the Covenanters. That’s fine. But they do need to take the Scottish background into account both to understand the context for the Westminster Assembly and the reasons behind American Presbyterians revising the Confession of Faith.