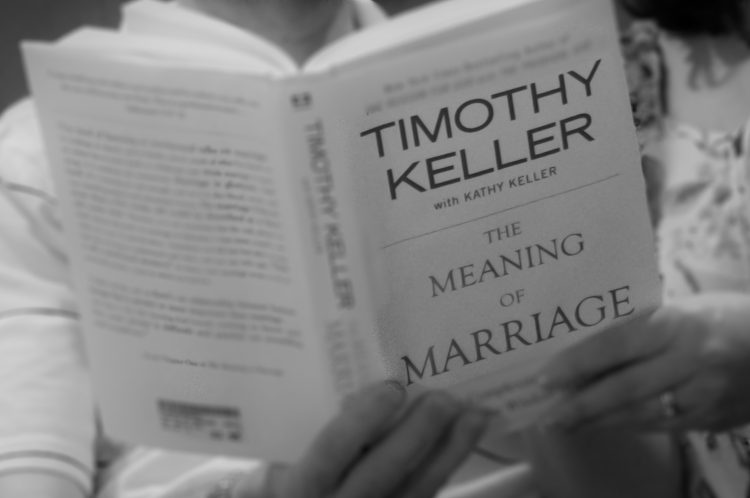

Rod Dreher doesn’t detect much daylight between the Benedict Option and Tim Keller even though I’ve tried to describe it. Here’s Keller (from Rod) on the West:

The crazy Christian gospel, so sneered at by the cultural elites that day, eventually showed forth its spiritual power to change lives and its cultural power to shape societies. Christianity met the populace’s needs and answered their questions. The dominant culture could not. And so the gospel multiplied.

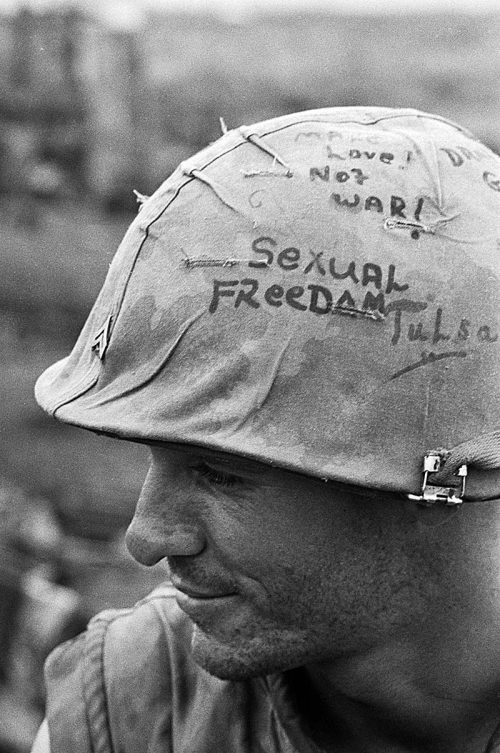

Do we have Paul’s courage, wisdom, skill, balance, and love to do the same thing today in the face of many sneering cultural leaders? It won’t be the same journey, because we live in a post-Christian Western society that has smuggled in many values gotten from the Bible but now unacknowledged as such. Late modern culture is not nearly as brutal as pagan culture. So the challenges are different, but we must still, I think, plunge into the agora as Paul did.

Here’s Rod’s rendering:

Does it surprise you that I agree with this? I’m still looking for ways in which Tim Keller and I substantively disagree on cultural engagement. If you know of any, please let me know — I’m serious about that. What I emphasize in The Benedict Option is that if we Christians are going to do that in a hostile, post-Christian public square, we have no choice but to take a step back from the public square to deepen our knowledge of the faith, our prayer lives, and our moral and spiritual discipline.

One difference right off the bat is that Keller is not pessimistic about the contemporary world, the way Rod is. That’s why it had to come as a surprise when Princeton Seminary thought Keller was too conservative and should not receive the Kuyper Prize.

Yet, Keller has other readers. Rod quotes one:

I’m somewhat favorably disposed to Tim Keller’s ministry, and even attended his church for a season. But that movement is likely to head off in its own direction. The current alliances that make up evangelicalism were forged in an era before liquid modernity. There is no reason why we should expect those alliances to continue to make sense in the very different social context that we face today. And we have to avoid the trap of conflating Christian orthodoxy with practical Christian wisdom. Families raising kids need something very different from a church community than what I need, as a 30-something professional who travels 50% of the time, usually in Asia….

Liquid modernity poses a certain challenge to Western rules-based cultures. Things change faster than our ability to develop rules to address certain situations. And that places a degree of stress on existing institutions, requiring them to be thicker than they were in the past. But it’s hard for institutions to be both thick and broad. For thickness to work, there has to be a high degree of overlap in people’s life situations. Demographic differences matter more.

I’m actually an advocate of an evangelical break-up. I believe that the Benedict Option is necessary. But the Benedict Option is going to look very different for different people. My fear is that evangelicalism ends up targeting the largest market, middle-class white suburbanites with kids, and castigated everyone else as a sinner. One need not look to hard for criticisms of Tim Keller’s efforts to reach out to people like me. And it disappoints me that Keller is largely silent in the face of those criticisms. If Christianity is to survive in an age of liquid modernity, it’s going to take more than suburban mega-churches.

Another difference then is that Rod thinks modernity is a force that hurts Christianity while Keller, like Pope Francis, tries to come along side moderns.

Still one more reader of Keller that Rod should enter into his Redeemer NYC spreadsheet:

Over the past decade or so, evangelical millennials like myself and my peers (and possibly even you), could be found across the country, repenting of our former fundamentalist ways.

We’ve put away our moralistic understanding of Christianity. We’ve reclaimed what is essential: Jesus, and his gospel. We’ve tossed aside our simplistic, and less than nuanced answers to those who criticize our faith and worldview.

Aided by an Internet-powered, Information Age, we have set out to re-engage culture in a fresh new way, following Tim Keller and Russell Moore on one end of the spectrum, or Rob Bell and Rachel Held Evans on the other.

As those who will soon lead the church, we are convinced that we are called to a new vision of cultural engagement and mission. . . .

Therefore, we’ve raised our sensitivity to xenophobic nationalism, misogyny, gay-bashing, microaggressions, and anti-intellectualism. For us, being uninformed and un-’woke’ is shameful and most harmful to our Christian witness.

Instead, we have taken up the mission to winsomely engage the brightest of thinkers in order that they might believe, and to prophetically rebuke the most narrow-minded of evangelicals in order that they might think.

We see far too little cultural influencers operating out of a biblical framework. And we’ve seen too many of our friends leave the faith due to overly simplistic, unsatisfying, and stale apologetic answers to their genuine contemporary questions.

We want to articulate, in a Keller-esque fashion, an attractive “third way,” between the liberals and the conservatives, between the irreligious and the religious. And in doing so, we hope to find a better place to stand, where we are neither apostates nor anti-intellectuals, neither prodigals nor older brothers.

So we continue to study Scripture and affirm its absolute authority, while still paying close attention to contemporary culture, the media, and the academy, seeking common grace insights from them, and wrestling with how to interpret and make sense of their findings.

We heed Peter’s exhortation that we be prepared to make a defense to all, while reminding ourselves of James’ admonition to be quick to listen, and slow to speak, even when it comes to a secular culture such as ours.

We don’t settle for just being Christians, but we seek to be informed, knowledgeable, and sensitive Christians. And by God’s grace, we sometimes do find a way forward, a third way, in which we actually become “believers who think,” equipped to interact with “thinkers” who don’t believe.

And discovering a “third way” feels good. It’s the rewarding feeling of progress, and confidence — confidence in the fact that we’ve found more thoughtful and persuasive answers than the ones our Sunday School teachers gave us 20 years ago. But it’s also the feeling of transcendence, and if we’re not careful, arrogant superiority.

Thinking Christians engaged with the world. That may not have been Paul’s advice to Timothy but it’s a page right out of Harry Emerson Fosdick:

Already all of us must have heard about the people who call themselves the Fundamentalists. Their apparent intention is to drive out of the evangelical churches men and women of liberal opinions. I speak of them the more freely because there are no two denominations more affected by them than the Baptist and the Presbyterian. We should not identify the Fundamentalists with the conservatives. All Fundamentalists are conservatives, but not all conservatives are Fundamentalists. The best conservatives can often give lessons to the liberals in true liberality of spirit, but the Fundamentalist program is essentially illiberal and intolerant.

The Fundamentalists see, and they see truly, that in this last generation there have been strange new movements in Christian thought. A great mass of new knowledge has come into man’s possession—new knowledge about the physical universe, its origin, its forces, its laws; new knowledge about human history and in particular about the ways in which the ancient peoples used to think in matters of religion and the methods by which they phrased and explained their spiritual experiences; and new knowledge, also, about other religions and the strangely similar ways in which men’s faiths and religious practices have developed everywhere. . . .

Now, there are multitudes of reverent Christians who have been unable to keep this new knowledge in one compartment of their minds and the Christian faith in another. They have been sure that all truth comes from the one God and is His revelation. Not, therefore, from irreverence or caprice or destructive zeal but for the sake of intellectual and spiritual integrity, that they might really love the Lord their God, not only with all their heart and soul and strength but with all their mind, they have been trying to see this new knowledge in terms of the Christian faith and to see the Christian faith in terms of this new knowledge.

For anyone who detects an example of the genetic fallacy, please write a note to Pastor Tim and ask him to explain how he avoids the errors that modernists like Fosdick committed.