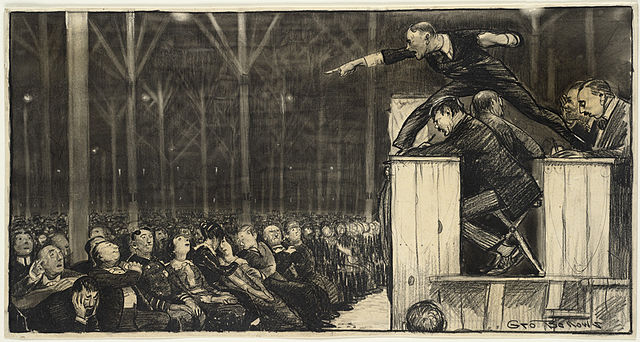

What a church with discipline (and even a little 2k) looks like:

[The] argument for Trump recalls an earlier episode in Catholicism and political theology, the condemnation of L’Action française (AF) by Pope Pius XI in 1927. AF was an anti-liberal political movement in early twentieth-century France. It was a monarchist and nationalist movement centering on the French literary figure Charles Maurras, who held that in order for France to become great again, she must exhibit a national, religious, and political unity that could only be achieved by sloughing off liberal republicanism and embracing “integral nationalism.”

Maurras himself had lost his Catholic faith and was an agnostic, but his “throne and altar” politics appealed to many Catholic clergy and laity. Maurras saw the Catholic Church as a French institution capable of uniting Frenchmen politically. The Church was basically an instrument for implementing Maurras’s cry of “la politique d’abord,” or “politics first!” (Compare this with Trump’s recent appeal to evangelical Christians.) Maurras was also politically anti-Semitic, for Judaism was not French and not a religion capable of uniting the French. Maurras later obtained the sixteenth seat in L’Academie française, the same seat occupied by Cardinal Dupanloup in the nineteenth century. He supported the Vichy regime and spent five years in prison after World War II for doing so. He died with little support, even though he had influenced an entire generation of French politicians and intellectuals, Charles de Gaulle among them.

In spite of Maurras’s anti-Semitism and because his movement promised restitution and renewed privilege for a beleaguered Church, many Catholics supported AF. The waves of the French Revolution had continued to break over the Church in France, with the most recent assault at the time being the 1905 Law of Separation, which finally separated the Church from the Republic, except that all Church property was placed under state ownership and under the management of government-supervised lay committees. To many French Catholics, the Law of Separation showed the futility of Leo XIII’s ralliement policy of trying to find a modus vivendi for French Catholics in the Third Republic’s secular democracy. Hence the swing to anti-liberal, monarchist, restorationist movements like AF, movements generally labeled “integralist.”

One of the Catholics supporting AF was Jacques Maritain, who had affiliated himself with AF on the advice of his spiritual director, Fr. Clérissac. Maritain hoped that he could temper the components of integral nationalism incompatible with Catholicism through his association with Maurras in their joint publication Revue Universelle, for which Maritain wrote for seven years.

The Vatican had contemplated a condemnation of AF for some time, and the Holy Office’s desire to place Maurras’s writings on the Index was checked only by the outbreak of World War I. But late in 1926 after hearing of more French Catholic youth joining AF, Pius XI prohibited Catholic membership in AF’s “school” and Catholic support for AF’s publications. In early 1927, the official condemnation and excommunications began, shocking many French Catholics. Two French bishops lost their sees for failing to comply with the condemnation, and the great ecclesiologist Billot lost his cardinal’s hat. Papal ralliement was here to stay, and any party spirit suffused with pagan attitudes was deemed incompatible with Catholic political involvement. The condemnations were a watershed moment for Maritain, who quickly began to reevaluate his political and social commitments in light of his ultimate commitment to the Catholic faith. His apology for the condemnation of AF, Primauté du spirituel (1927), set the trajectory for his most famous political works, Humanisme intégral (1936) and Man and the State (1951). These works later influenced the Fathers of Vatican II, including Pope Paul VI.

It is possible for popes to act even when they are not temporal princes.

The Vatican wanted Catholics to refuse an attractive but ultimately self-defeating choice in supporting AF, and today American Catholics face a similar sort of choice. Now Trump is dissimilar to Maurras in many ways. The latter was revered for his intellectual and literary ability and had coherent and firm philosophico-political commitments, while Trump has demonstrated a shocking ignorance of Christianity and malleable, opportunistic political positions. Although both in a sense promoted the “liberty of the Church,” Maurras did so through throne and altar restorationism while Trump does so through an appeal to religious liberty.

So what’s the lesson?

The lesson from the AF crisis bears mentioning today. The Church, both her teaching office and her living members, constantly must discern whether new means for political action are compatible with a genuine concern for the common good and the integrity of Catholics involved in politics.

Is such discernment the consequence of losing confidence in the bishops?

Who is going to save our Church? Do not look to the priests. Do not look to the bishops. It’s up to you, the laity, to remind our priests to be priests and our bishops to be bishops. Archbishop Fulton Sheen

But I thought episcopacy and apostolic succession was what made Protestantism look like such a poor alternative for western Christians.