You might read something like this (from the Spring 2009 issue – a roundtable on the state of the Presbyterian Church in America):

Can This Marriage Be Saved?

Just to lay my cards on the table up front, I will admit that both my ecclesiastical background and my geographical location are very different from Mr. Dunahoo’s. Having been reared in megachurch evangelicalism in Southern California, and currently pastoring a PCA in the Seattle area, I have neither the broadness of perspective that Dunahoo enjoys, nor the memories of this denomination’s early days that he retains. Still, I’ll do my best to make some worthwhile remarks about the Presbyterian Church in America, both present and future.

Dunahoo lists five distinct groups within the PCA. In my four years as a member of the Pacific Northwest Presbytery, I can identify groups 1 and 2 (the “Reformed Fundamentalists” and the “Reformed Evangelicals”) in this neck of the ecclesiastical woods. That’s not to say the others don’t exist elsewhere, but as I said, my experience is limited to the fringe of the movement (“fringe” being used literally with respect to my presbytery’s location, and perhaps metaphorically with respect to its self-perception. More on this below). Now although I balk at the label affixed to me by Dunahoo (I happen to think of “Fundamentalist” as rather antithetical to “Reformed”), I do consider myself to fit squarely into his first category. I believe the Westminster Confession and Catechisms to be the most faithful articulation of biblical truth, and I believe that it is my calling and duty as a minister to expound Holy Scripture through the lens of the doctrinal standards to which I have submitted myself.

I would venture to say that Dunahoo’s second group, the Reformed Evangelicals, is the largest subgroup within the PCA. I may be wrong about this, but my excuse for such misperception is that the denomination’s official publications, as well as its seminary, all seem to presuppose the missional model, with hardly a paragraph being written in their literature that doesn’t remind the reader to redeem this or transform that. Words like “contextual” and “incarnational” are nearly as important in church planting circles as the phrases “Word and sacraments” or “the ordinary means of grace.” Apparently, word, water, and wine are all well and good provided they’re dispensed with sufficient cultural exegesis and social sensitivity. But I digress.

What I do find refreshing about Dunahoo’s perspective is, well, its perspective. In other words, he doesn’t simply draw a circle around himself and his friends and act as if there is no one else in the denomination besides his own subgroup. The reason I mention this is that I know what it is like to be treated like a virtual alien simply because I haven’t drunk the contextual Kool-Aid. I still feel the sting from the lashing I received at the PCA’s Church Planters’ Assessment when, in a certain exercise, I dared use the word “covenantal” while giving a mock church planting presentation to a pretend presbytery. Apparently it is a cardinal sin to assume that presbyters in the PCA understand the nomenclature used in chapter seven of the Westminster Confession (I’m not bitter anymore, really). My point here is that the sooner the confessionalists and transformationists (or, groups 1 and 2) recognize each other’s existence, the better. True, the two may never become one, but at least they’ll realize they are shacked up as roommates in the same house.

In the Pacific Northwest Presbytery where I am a member, the line dividing the Reformed Fundamentalists from, well, everyone else was recently made painfully apparent. At our stated meeting in October 2007, Rev. Peter Leithart and I jointly requested that presbytery appoint a study committee to evaluate Leithart’s Federal Visionist views and compare them with the Westminster Confession, with a particular emphasis on the nine “Declarations” of the previous summer’s General Assembly report on Federal Vision theology more broadly. The committee ended up split 4-3, with the majority concluding that Leithart’s views, though at times confusing and unhelpful, were nonetheless within the bounds of confessional orthodoxy, while the minority (of which I was a part) found his views to strike at the vitals of the Reformed system of doctrine.

When we met a year later to present the reports, the debate on the floor of presbytery was rather telling (to say the least) in that it largely ignored the narrow issues that the committee was charged to address and focused instead on the larger (and, strictly speaking, irrelevant) question, “What is the PCA?” The concerns voiced were primarily focused on self-identity instead of whether Leithart’s theology was Reformed or not. The greatest fear on the part of the members of presbytery was that by voting to depose one of our own we’d become, well, like the OPC. In other words, we already represent a mere fraction of Christian believers anyway, and now, by defrocking everyone who fails to cross their t’s and dot there i’s the way we’d like them to, we will just paint an even smaller circle around ourselves, eventually paling into utter obscurity and irrelevance.

It seems to me that the events of the Pacific Northwest Presbytery’s October 2008 meeting demonstrate, albeit microcosmically, the identity crisis of the PCA as a whole. As the “A” in our name would seem to suggest, we are perhaps unduly fixated on being big, noteworthy, and successful, and whatever stands in the way of such success must be viewed with a measure of suspicion. Hence the ho-hum attitude on the part of Dunahoo’s “Reformed Evangelicals” towards a simple, ordinary-means-of-grace ministry that dismisses the fanfare and obsession with how many artists show up at our wine- and cheese-tasting soirees, and gives attention rather to preaching Christ and administrating the Supper each Lord’s Day. As much as the OPC’s obvious irrelevance (ahem) stands as an ominous warning to the movers and shakers at Covenant Seminary and sends chills down the collective spine of the powers that be in Atlanta, the fact is that our older cousin, though a runt in the Presbyterian litter, enjoys the freedom of Mere Presbyterianism to a degree that the PCA cannot (at least not as long as we’re pining for the approval of the artsy-fartsy, the bohemian, the indy, and the soul-patched).

Not being prone to prognostication, I am loath to guess where the rocky marriage between the confessionalists and transformationists will take the PCA. If Tim Keller’s work with the Gospel Coalition is any indication, it is at least possible that the Reformed Evangelicals will continue to value cultural engagement and renewal more highly than confessional exactitude, perhaps to the point of secession. Or to look at it from the other direction, if the so-called Reformed Fundamentalists continue to be made to feel hopelessly irrelevant and out of touch when we settle for a Sabbath-oriented, means-of-grace-driven piety, a withdrawal could potentially occur. Then again, we could just continue with the live-and-let-live, quasi-congregationalism that we now enjoy, according to which I can be left alone to don my Geneva gown on Sunday provided I don’t hassle the PCA pastor in the next town over for using multimedia and drama to reach the “teenz.”

But either way, the Emergents are certainly right about one thing: the church, if not a mess, is nonetheless messy.

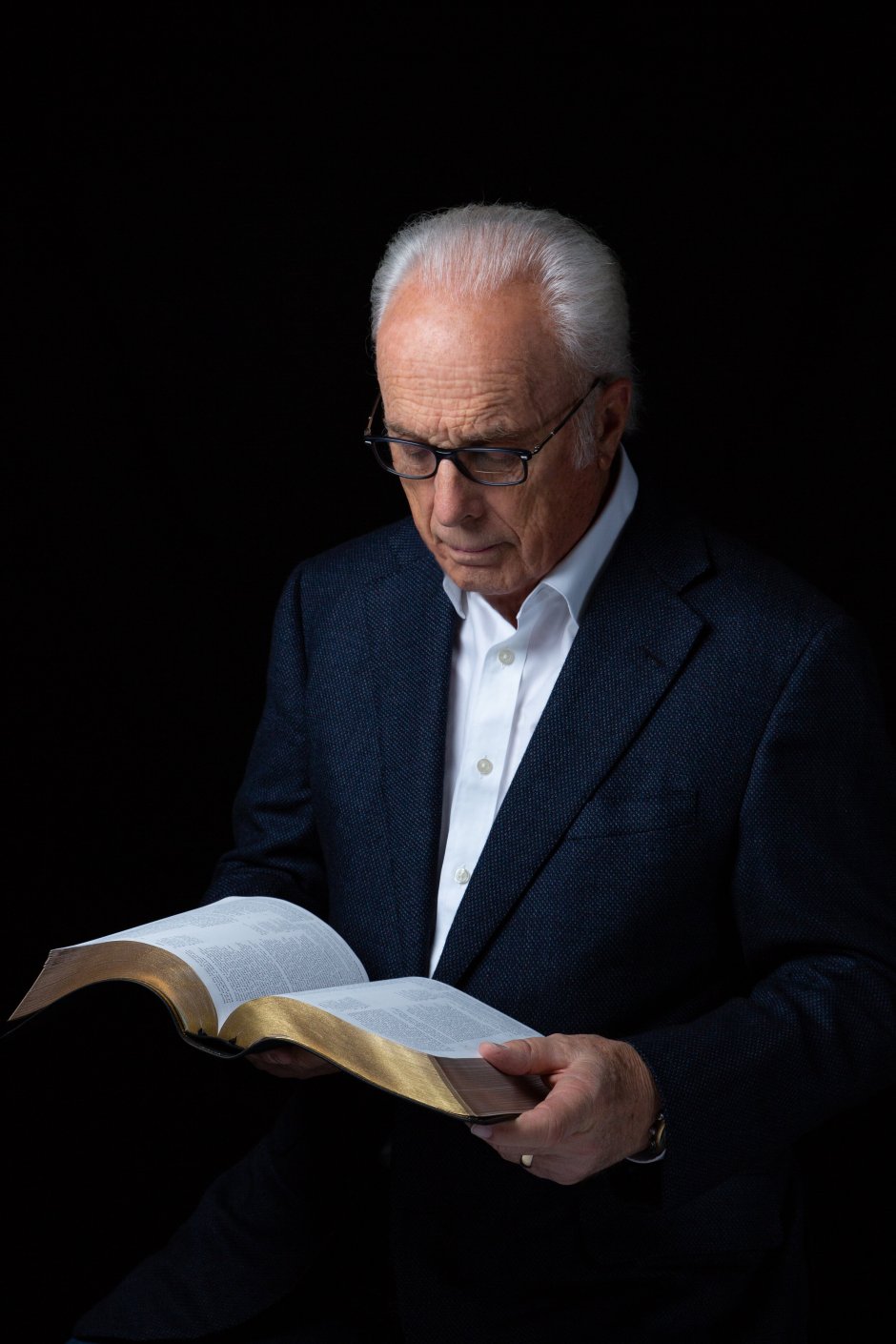

Jason Stellman is pastor of Exile Presbyterian Church (PCA) in Woodinville, Washington.