I have already wondered how you can throw around the phrase, white normativity, and not also need to add heternormativity to your Christian activism. But Andrew Sullivan, a man who is gay, married, Roman Catholic, and identifies as conservative, also gives reason for thinking that woke evangelicals and Reformed Protestants are playing with fire if they think they can hold on to doctrinal normativity while berating white normativity and remain silent (or not) about heteronormativity.

First, without even using the phrase, “cultural Marxism,” Sullivan explains why some Americans find the Left, and their woke evangelical supporters, scary (yes, it may be okay to be afraid):

A conservative who becomes fixated on the contemporary left’s attempt to transform traditional society, and who views its zeal in remaking America as an existential crisis, can decide that in this war, there can be no neutrality or passivity or compromise. It is not enough to resist, slow, query, or even mock the nostrums of the left; it is essential that they be attacked — and forcefully. If the left is engaged in a project of social engineering, the right should do the same: abandon liberal democratic moderation and join the fray.

I confess I’m tempted by this, especially since the left seems to have decided that the forces behind Trump’s election represented not an aberration, but the essence of America, unchanged since slavery. To watch this version of the left capture all of higher education and the mainstream media, to see the increasing fury and ambition of its proponents, could make a reactionary of nearly anyone who’s not onboard with this radical project.

Of course, Sullivan is not ready to join the OPC or to sign the Statement on Social Justice and the Gospel. He recognizes a difference between supporting Trump as the embodiment of American norms and seeing Trump as a hedge on the Left’s attempt to remake the nation (even while breaking things):

This, it strikes me, is one core divide on the right: between those who see the social, cultural, and demographic changes of the last few decades as requiring an assault and reversal, and those who seek to reform its excesses, manage its unintended consequences, but otherwise live with it. Anton is a reactionary; I’m a conservative. I’m older than Anton but am obviously far more comfortable in a multicultural world, and see many of the changes of the last few decades as welcome and overdue: the triumph of women in education and the workplace; the integration of gays and lesbians; the emergence of a thriving black middle class; the relaxation of sexual repression; the growing interdependence of Western democracies; the pushback against male sexual harassment and assault.

Yes, a conservative is worried about the scale and pace of change, its unintended consequences, and its excesses, but he’s still comfortable with change. Nothing is ever fixed. No nation stays the same. Culture mutates and mashes things up. And in America, change has always been a motor engine in a restless continent.

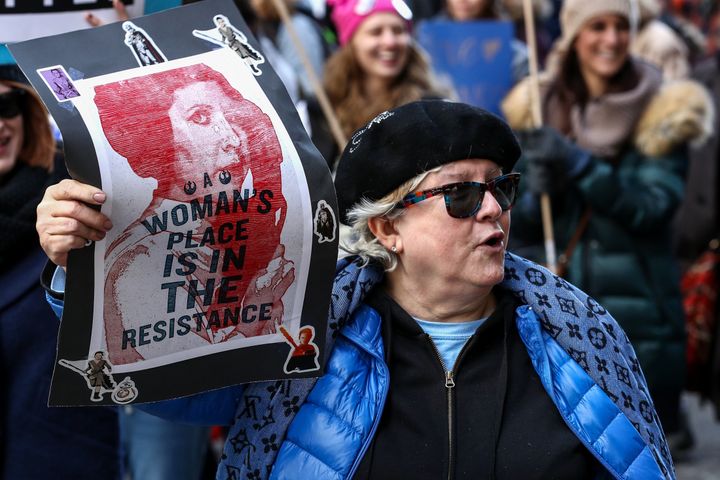

But you are not a white racist Christian nationalist supremacist misogynist sinner (where do you put guns?) if you don’t agree with the ladies or men of color who host certain podcasts:

In a new essay, Anton explains his view of the world: “What happens when transformative efforts bump up against permanent and natural limits? Nature tends to bump back. The Leftist response is always to blame nature; or, to be more specific, to blame men; or to be even more specific, to blame certain men.” To be even more specific, cis white straight men.

But what are “permanent and natural limits” to transformation? Here are a couple: humanity’s deep-seated tribalism and the natural differences between men and women. It seems to me that you can push against these basic features of human nature, you can do all you can to counter the human preference for an in-group over an out-group, you can create a structure where women can have fully equal opportunities — but you will never eradicate these deeper realities.

The left is correct that Americans are racist and sexist; but so are all humans. The question is whether, at this point in time, America has adequately managed to contain, ameliorate, and discourage these deeply human traits. I’d say that by any reasonable standards in history or the contemporary world, America is a miracle of multiracial and multicultural harmony. There’s more to do and accomplish, but the standard should be what’s doable within the framework of human nature, not perfection.

Sullivan’s point about the Left blaming nature is what seems to be missing from the self-awareness of woke Protestants. They may agree and receive inspiration from opposing racial and gender hierarchies. But for the Left, these antagonism stem from a willingness to overturn nature. That is a line that Christians should not cross if they want to continue to believe in the God who created humans as male and female, and creatures as feline and canine. You start to argue that to achieve equality we need to do away with natural distinctions and you are going to have trouble with the creator God.

One last point from Sullivan that shows how woke Christians are becoming fundamentalist, but with a real kicker:

This week, I read a Twitter thread that was, in some ways, an almost perfect microcosm of this dynamic. It was by a woke mother of a white teenage son, who followed her son’s online browsing habits. Terrified that her son might become a white supremacist via the internet, she warns: “Here’s an early red flag: if your kid says ‘triggered’ as a joke referring to people being sensitive, he’s already being exposed & on his way. Intervene!” Really? A healthy sense of humor at oversensitivity is a sign of burgeoning white supremacy? Please. More tips for worried moms: “You can also watch political comedy shows with him, like Trevor Noah, John Oliver, Hasan Minhaj. Talk about what makes their jokes funny — who are the butt of the jokes? Do they ‘punch up’ or down? … Show them that progressive comedy isn’t about being ‘politically correct’ or safe. It’s often about exposing oppressive systems — which is the furthest thing from ‘safe’ or delicate as you can get.”

It reminds me of a fundamentalist mother stalking her son’s online porn habit. Doesn’t she realize that it is exactly this kind of pious, preachy indoctrination about “oppressive systems” that are actually turning some white kids into alt-right fanboys? To my mind, it’s a sign of psychological well-being that these boys are skeptical of their authority figures, that they don’t think their maleness is a problem, and that they enjoy taking the piss out of progressive pabulum. This is what healthy teenage boys do.

More to the point, this kind of scolding is almost always counterproductive. Subject young white boys to critical race and gender theory, tell them that women can have penises, that genetics are irrelevant in understanding human behavior, that borders are racist, or that men are inherently toxic, and you will get a bunch of Jordan Peterson fans by their 20s. Actually, scratch that future tense — they’re here and growing in number.

Many leftists somehow believe that sustained indoctrination will work in abolishing human nature, and when it doesn’t, because it can’t, they demonize those who have failed the various tests of PC purity as inherently wicked. In the end, the alienated and despised see no reason not to gravitate to ever-more extreme positions. They support people and ideas simply because they piss off their indoctrinators. And, in the end, they reelect Trump.

Re-elect Trump or no, you have ideological purity.