Darren Dochuk’s new book, Anointed with Oil: How Christianity and Crude Made Modern America, continues his study of American Protestantism’s financial profile. A very simple way of putting his findings is to say that John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil financed mainline Protestant organizations and J. Howard Pew (and other small oilmen) sustained evangelical Protestantism. In his own words:

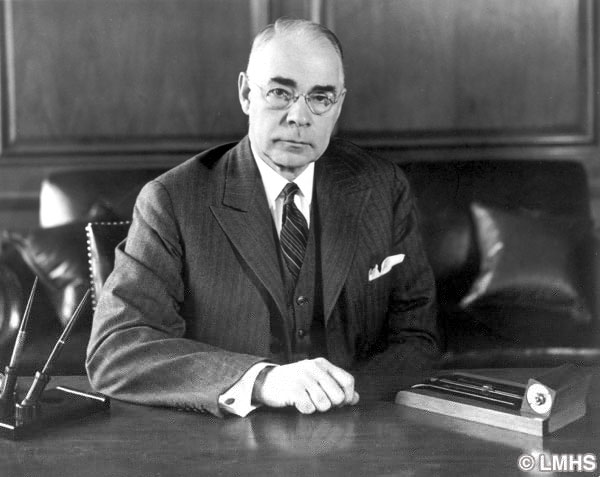

By the late 1940s, Howard was not only bitter about major oil’s global expansion at the cost of U.S. domestic production (and with Washington’s privileging of that trend), but also about how the Rockefellers were reshaping society with their mammoth charity. John D. Rockefeller Jr., and his sons were, by now, heading a multifaceted foundation that sought to provide humanitarianism and economic development on an international scale. In Pew’s mind, it was the Rockefellers’ brand of ecumenical, interdenominational and internationalist (“monopolistic”) Protestantism, and its prioritizing of science and structural reform over personal matters of the soul that was responsible for the nation’s secular slide. Determined to offset the Rockefellers’ modernistic gospel, in 1948 Pew helped his siblings incorporate the Pew Memorial Trust to “help meet human needs” through support of “education, social services, religion, health care and medical research,” then christened his own, the J. Howard Pew Freedom Trust, whose charge was even bolder: “to acquaint the American people with the values of a free market, the dangers of inflation, the paralyzing effects of government controls on the lives and activities of people” and “promote the recognition of the interdependence of Christianity and freedom.”

That stance in opposition to Protestant modernism and ecumenism prompted Pew to be a major backer of the neo-evangelicals (later just plain evangelicals) at institutions like Fuller, Christianity Today, Billy Graham (Inc.), and Gordon-Conwell:

the Pews rigorously protected personal liberty in theological terms. Howard continued that tradition in the Cold War years. While serving as chair of the National Lay Committee in the National Council of Churches, he agitated against the “collectivist” drift in Presbyterianism and America’s Protestant mainline.

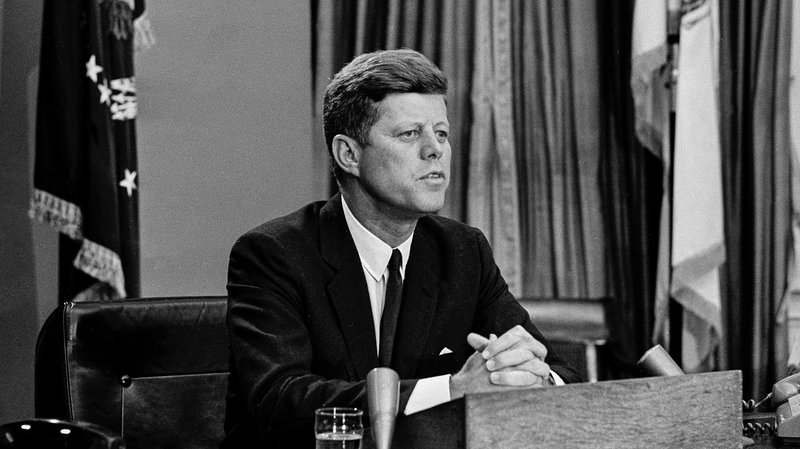

He found another way to push back by funding pastors, seminaries and lobbies associated with “new evangelicalism,” the loosely coordinated movement that would lay the groundwork for the religious right. In one respect, new evangelicals sought simply to continue a fight against liberal “modernist” trends in American Protestantism and society that self-identified “fundamentalists” had waged in the previous half century. Thanks to the unmatched financial support of independent oilmen Lyman and Milton Stewart, the brother tandem at the helm of Union Oil Company of California (whose own hatred of the Rockefellers knew no bounds), fundamentalists had proved highly successful at constructing an alternative infrastructure of churches, missionary agencies and schools that resisted progressivism’s pull. Yet new evangelicals, unlike fundamentalists, wanted to engage rather than recoil from mainstream society—they sought to redeem it rather than run from it. The number of institutions within the new evangelical orb that would benefit from Pew’s millions would be spectacularly large, including illustrious representatives such as Christianity Today, the National Association of Evangelicals and evangelist Billy Graham. Graham and his friends were known to lean on the “big boys” of southwestern oil for financing, among them the superrich Sid Richardson and Hugh Roy Cullen. But J. Howard Pew was the biggest backer among them.

The thing is, confessional Protestants fell between the cracks of categories like liberal and evangelical Protestants, but also sometimes drew fire from oilmen like Pew. (Machen actually preached at the union congregation in Seal Harbor, Maine, at the invitation of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the place where the Machens and Rockefellers worshiped while on vacation.)

When the OPC began, its original name was the Presbyterian Church of America (not to be confused with “in America”). That was a bridge too far (aside from the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions) for mainline Presbyterians. In 1935 while J. Gresham Machen and other board members belonged to the PCUSA, opposition to conservatives could use ecclesiastical courts. But once Machen was convicted of breaking church law and excommunicated, the only recourse to stop his efforts was the civil courts. And so, the PCUSA brought a civil suit against the new Presbyterian communion and asked the judge to force the new communion to change its name. Here was part of the PCUSA’s reasoning (humor warning):

It is impracticable and impossible for the plaintiff church to recover in damages what it has suffered and is likely to suffer from the aforesaid acts done and threatened to be done by and on behalf of the defendant church. The plaintiff church is powerless to prevent the resulting injury to its property and enterprises, or to avoid the resulting loss in donations and financial support which may be diverted from it, which injuries are immediate, continuous and irreparable, and incapable of computation or estimate. (Bill of Complaint, reprinted in Presbyterian Guardian, Sept. 12, 1936)

To put readers’ laughter in perspective, here are some figures to keep in mind for comparison between the PCUSA and the original OPC:

At its first General Assembly the [OPC] counted only thirty-four ministers, with roughly thirty congregations and 5,000 members. Funds were so scarce that the minutes of the first five General Assemblies do not even include financial reports. No doubt the ministers themselves bore most of the expenses of the denomination and its proceedings, with help from congregations. The only mention of finances at the third General Assembly, for example in 1937, was in connection with the costs for printing the minutes and agenda, and the budget of the Committee on Home Missions and Church Extension. Printing costs were $137 and the receipts from churches and ministers were only $122, leaving a deficit of $15. Because the Committee on Home Missions was the only agency with a real budget, the delegates passed along the rest of the bill to Home Missions. But that committee was not exactly flush. Their expenses for the first year came to just short of $13,000, with receipts totaling a little more than $13,000. In fact, the Committee on Home Missions’ budget was the OPC’s denominational budget. In addition to picking up the expenses of printing the General Assembly’s minutes, the Committee also footed the bill for renting the hall where the Assembly met. Thus, by the end of its first year the OPC’s total assets, if the balance of the Committee on Home Missions’ bank account is any indication, were $221.54.

In contrast, the PCUSA’s wealth and stature were truly staggering. In their complaint against the OPC the officers of the mainline denomination listed their resources to show how much they had to lose if a new church came along with a similar name. The PCUSA had close to 9,000 congregations, with just under 2 million church members, and 9,800 ministers. The church had approximately 1,600 home missionaries with an annual budget of $2.5 million and trust funds totaling just over $33 million. The PCUSA’s efforts in foreign missions were also large. They counted 1,300 missionaries with an annual budget of $2.9 million and trust funds totaling a little more than $18 million.

The [OPC] did not even send out their first foreign missionaries until 1938 and then could only manage support for eight, a number figure that included wives. (DGH, “Why the OPC: The History behind the Name)

What does this have to do with big oil or J. Howard Pew? The first two names on the Bill of Complaint were:

THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA By (Sgd) HENRY B. MASTER, Moderator

TRUSTEES OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA By (Sgd) J. HOWARD Pew, President.

This does not mean that Pew was aiming for Machen and the OPC. He likely signed this complaint as part of his responsibilities as an elder in the PCUSA.

But, the man who funded so much of the neo-evangelical world, the friend of so-called conservative Protestants, was right there in the legal proceedings against other conservative Protestants, the ones who were the most Presbyterian of all the Protestants (minus the Covenanters, and Associate Reformed). And one reason that Pew might have favored Graham et al and not had much regard for Machen was the the latter’s understanding of the mission of the church was not going to abet the political and economic policies that Pew wanted the federal government to pursue. Graham and the neo-evangelicals, sorry Mark Galli, wanted to be evangelicalism for the nation. That earned them Pew’s support.