I second John’s question and raise him a question. What am I missing about Islam that has so many people acting like Muslims are like United Methodists? I don’t mean to imply that all Muslims are terrorists any more than all Methodists follow John Wesley. But for Never Trumpers to argue about Islamophobia as if fears of Muslims are irrational — precisely forty years into various forms of Islamic terrorism, and while ISIS has been a major source of news coverage — is well nigh extraordinary.

Did anyone remember, for instance, when Graeme Wood wrote a piece not in the American Spectator but in Atlantic Monthly about ISIS’ Islamic convictions?

The most-articulate spokesmen for that position are the Islamic State’s officials and supporters themselves. They refer derisively to “moderns.” In conversation, they insist that they will not—cannot—waver from governing precepts that were embedded in Islam by the Prophet Muhammad and his earliest followers. They often speak in codes and allusions that sound odd or old-fashioned to non-Muslims, but refer to specific traditions and texts of early Islam.

Now if you want to distance the Muslim Brotherhood from terrorism, fine. But that doesn’t get you the faculty of Harvard University:

It’s fine to think that the Muslim Brotherhood is bad, terrible, authoritarian, or illiberal (in my book on the Egyptian and Jordanian Brotherhoods from the 1980s till today, I highlight the group’s illiberal nature at length). Eric Trager, who I have disagreed with quite strongly on matters relating to the Brotherhood, has called it more akin to a “hate group.” But even he has written against designation. The Brotherhood’s badness, one way or the other, has no bearing on whether or not it is a terrorist organization. Being a terrorist organization involves, among other things, ordering your members to commit terrorist attacks, something no one argues the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood is doing.

Even promotional copy for events featuring two of the most western friendly and thoughtful interpreters of Islam, Mustafa Akyol and Shadi Hamid, notice that Muslim societies are not places where Washington Post editors send their children for university:

Predominantly Muslim societies suffer from low levels of political, economic, and civil liberties. Authoritarian political regimes, rigid social structures, and radical religious movements that suppress human liberty in the name of God loom large in the Muslim world. Is this liberty deficit due to a “dark age” of Islam, which can be overcome with reform and a different religious interpretation? Can Islam make its peace with liberal democracy, as Christianity and other religions did after their own illiberal ages? Or is there something different about Islam, making it inherently incompatible with a secular government and a free society? Mustafa Akyol, a longtime defender of “Islamic liberalism,” is optimistic. Shadi Hamid is more pessimistic, arguing that Islam is “exceptional,” in the sense of being essentially resistant to liberalism.

Maybe you want to claim that it’s all a matter of interpretation — some truth there — but that still leaves you having to distinguish better from worse versions of Islam according western liberal standards, which in and of itself means Islam is not United Methodism.

For that reason, it’s a little rich when Michael Schulson writes as if the problems of perception that surround Islam are really the constructions of President Trump and his advisers:

It is difficult to think of a definition of religion that does not include Islam — an ancient tradition with practitioners who believe in one God, pray and try to live their lives in accordance with a scripture.

So why has this particular canard taken off?

Wajahat Ali, a writer, attorney, and the lead author of “Fear, Inc.,” a report on American Islamophobia, traces the idea’s recent surge to anti-Islam activists David Yerushalmi and Frank Gaffney. In 2010, Gaffney’s Center for Security Policy published a report, “Shariah: The Threat to America,” arguing that Muslim religious law, or sharia, was actually a dangerous political ideology that a cabal of Muslims hoped to impose on the United States.

“Though it certainly has spiritual elements, it would be a mistake to think of shariah as a ‘religious’ code in the Western sense,” the report argued. It also suggested banning “immigration of those who adhere to shariah … as was previously done with adherents to the seditious ideology of communism.”

“They misdefine sharia in a way which is not recognizable to any practicing Muslim,” Ali said. But the idea was influential. By the summer of 2011, more than two dozen states were considering anti-sharia legislation. More recently, Gaffney reportedly advised Trump’s transition team.

For many Americans, confusion about religious law, political ideology and sharia may reflect a distinctly Christian, and especially Protestant, way of thinking about the nature of religion.

“It’s hard to talk about this sometimes because there is no equivalent of sharia in the Christian tradition,” said Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of “Islamic Exceptionalism: How the Struggle Over Islam Is Reshaping the World.” “Even when you’re talking to well-intentioned, well-meaning people who really want to understand, explaining sharia is very challenging because there’s nothing in Christianity that’s quite like it.”

Actually, Christianity does have its equivalent. The mainstream media has called them theocons and Damon Linker, who wrote a book by that title, copped the plea:

Bannon and the intellectuals Neuhaus regularly published in First Things share the conviction that, at a fundamental level, the United States is a Christian nation — not just in the sense that an overwhelming majority of Americans describe themselves as Christians, but also in the sense that the country’s highest ideals and convictions (above all, about individual rights and innate human dignity) derive from a Catholic-Christian inheritance the vitality of which must be actively fostered and promoted by the culture. The two groups also tend to view the threat posed by Islamic terrorism in terms of a civilizational clash between Islam and the Judeo-Christian West (or “Christendom”).

But that’s where the continuities end.

At their best, the original theocons followed a tradition of Christian political reflection that insisted on placing the nation under the guidance and judgment of a transcendent God (and his extra-political Church) that stands apart from all this-worldly communities. That was in fact the theme of Neuhaus’ final book, published shortly after his death from cancer in early 2009.

Bannon, by contrast, tends to treat religious affiliation wholly as a function of ethno-national identity: “We” in the West must affirm our Christian identity or we will be overrun by dangerous outsiders (Islamists) who will impose a different identity upon us. In this respect, Bannon’s position is closer to Eastern Orthodoxy (and Russian Orthodoxy in particular), with its sanctioning of an official ethno-national church that mediates between individual believers and the Godhead.

Yet, to Linker’s credit, he can tell the difference between a good theocon and a fear-inspiring one, unlike many social justice types who think the campus of Princeton University is just like Ferguson, Missouri. I do wonder, though, if he remembers how his editors at Doubleday trumped up his book?

Do you believe the Catholic Church should be actively intervening in American politics on the side of the Republican Party?

Do you believe the federal government should be channeling billions of tax dollars a year to churches and other religious organizations?

Do you believe a microscopic clump of cells in a petri dish possesses the same rights that you possess?

Do you believe a doctor who performs abortions — and a woman who chooses to have an abortion — should be arrested and charged with murder?

Do you believe the public schools should actively teach children to doubt the scientific theory of evolution?

Do you believe legally available contraception is producing a “culture of death” in the United States?

Do you believe that the United States should be a Christian nation?

Do you fear Christians because you don’t fear Muslims?

No reason to fear Islam, no not one. Just think professional boxing and the NBA:

Can we imagine an America without Muhammad Ali, who was born Cassius Clay in Louisville and gained national fame when he won a gold medal at the Rome Olympics in 1960 as a light heavyweight boxer? In 1964, Clay defeated Sonny Liston, becoming the world heavyweight boxing champion. A few years earlier, Clay had gone to Nation of Islam meetings. There, he met Malcolm X, who as a friend and advisor was part of Clay’s entourage for the Liston fight. Clay made his conversion public after the fight, and was renamed by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad as Muhammad Ali.

When he was reclassified as eligible for induction into the draft for the Vietnam War, Ali refused on the grounds of his new Muslim religious beliefs. Famously, reflecting on the racism he had experienced in America, Ali said, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong—no Viet Cong ever called me ni**er.” His conscientious objector status was rooted in the teachings of the Nation of Islam, as Elijah Muhammad had earlier been jailed for his refusal to enter the draft in the Second World War.

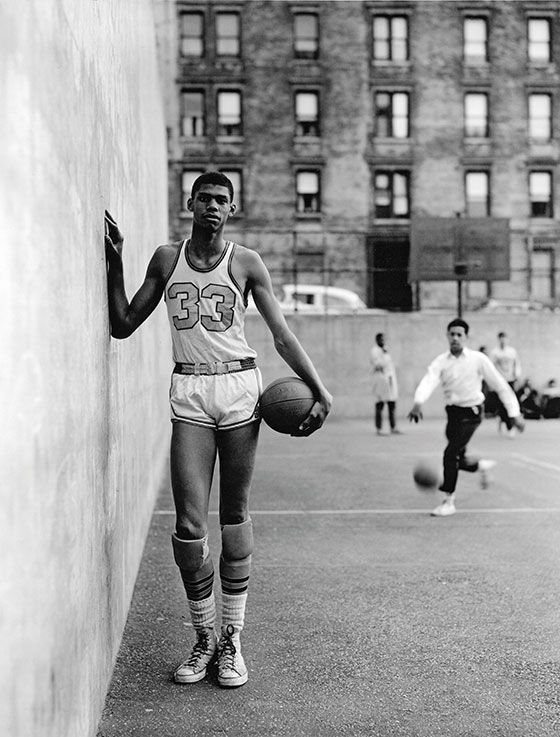

. . . Or think of my other great hero, another American Muslim, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. The greatest basketball coach ever, the late John R. Wooden, thought that Kareem was the greatest basketball player ever. In his three years of eligibility under Coach Wooden at UCLA, Kareem was three-time player of the year, three-time finals MVP, and three-time NCAA champion. In other words, he had three perfect seasons while he earned his degree. He lost the same number of games at UCLA—two—that he did in high school.

Kareem converted to Islam in 1971, and excelled in the pros just as much as he did in college or high school. All in all, he won six NBA championships and six NBA MVP awards, was a nineteen-time all-star, and remains the NBA’s all-time leading scorer. Combine that pro record with his three NCAA championships, and I don’t know how you can make the case for anyone else as the greatest basketball player of all time.