Let the record show, Princeton University, during the last wave of heightened aesthetic consciousness about public art, had a chance, just like Mayor James Kenney in Philadelphia (with the Frank Rizzo statue), to get rid of Woodrow Wilson’s name at its School of Public and International Affairs. The university, with the same president as today, Christopher Eisgruber, decided to keep the Wilson name. Here is part of Princeton’s reasoning:

The challenge presented by Wilson’s legacy is that some of his views and actions clearly contradict the values we hold today about fair treatment for all individuals, and our aspirations for Princeton to be a diverse, inclusive, and welcoming community. On the other hand, many of his views and actions – as faculty member and president of this University, as governor of New Jersey and a two-term President of the United States, and as an international leader whose name and legacy are still revered in many parts of the world – speak directly to our values and aspirations for our school of public and international affairs and for the first of our residential colleges.

… There is considerable consensus that Wilson was a transformative and visionary figure in the area of public and international affairs; that he did press for the kinds of living and learning arrangements that are represented today in Princeton’s residential colleges; and that as a strong proponent of education for use, he believed Princeton should prepare its students for lives in the nation’s service. These were the reasons Wilson’s name was associated with the school, the college, and the award.

The question that immediately comes to mind is how do the people who punted on Wilson in 2016 get to keep their jobs and positions? They looked at the evidence, and even heard from scholars who were decidedly negative in their estimates of Wilson, such as this one from the University of Richmond’s Eric S. Yellin:

Far from being merely ignorant “men of their times,” Wilson and his administration sought to do something new when they delegitimized public objections to segregation by marking any protest as both insubordinate and fallacious. African Americans and some allies never accepted this argument, of course, but the vast majority of white Americans did not question it. In this way, federal discrimination, including administrators’ explanations of it, played its part in the national institutionalization of white supremacy in the United States in the early twentieth century.

Again, for the record, Princeton’s president and board of trustees read these words and decided to keep Wilson’s name. Why don’t they too need to vacate Princeton the way Wilson has? Could you have a better indication of racism according to 2020 standards?

By the way, it was a curious group of advisors to Princeton who commissioned reactions from historians and issued a report that kept Wilson’s name. It had nary an academic on it except for a retired president of Brown University. Otherwise, the ten member committee, chaired by an African-American attorney, Brent L. Henry, consisted of executives, financiers, lawyers, leaders of non-profits, and one writer (five men, five women — cisgender I presume; five whites, five non-white). Anyone of a social justicey inclination might well wonder whether these people too need to be cancelled.

Princeton’s administration did see in 2016 the ripple effects of Wilson’s reputation. In 1948, when the school of government took Wilson’s name, Harold Willis Dodds was president (a Grove City alum). Instead of removing Wilson’s name in 2017, the University decided to move Dodds’ name within the Robertson Hall (the modernist building from 1961 designed by the same architect behind New York City’s World Trade Center. What the University did was to rename Dodds Auditorium in Robertson as the Arthur Lewis Auditorium. Dodds’ name was downsized to Robertson Hall’s Atrium.

Relatives of Dodds were not happy. John A. Dodds, a nephew of the former president, and member of the class of 1952, wrote to the alumni magazine:

it appears to me that my uncle has been inadvertently affected by some of the fallout over Woodrow Wilson 1879. This change was planned to go into effect as of July 1.

Now it appears that Princeton is even more interested in fulfilling its mission of amplifying diversity and political correctness than honoring a man who served longer as president of Princeton University (1933–57) than any other Princeton president in the 19th or 20th century. He brought the University through some difficult times during World War II, and his longevity as president attests to his inherent skills.

What next, a potted plant with his name on it?

These odd details amplify what Ross Douthat wrote about the name change as being more ephemeral than substantive:

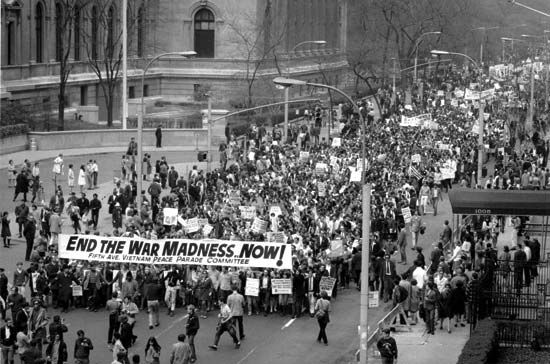

the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs wasn’t named for Wilson to honor him for being a segregationist. It was named for him because he helped create precisely the institutions that the school exists to staff — our domestic administrative state and our global foreign policy apparatus — and because he was the presidential progenitor of the idealistic, interventionist worldview that has animated that foreign policy community ever since.

Which means, in turn, that the school will remain his school, whatever name gets slapped upon it, so long as it pursues the projects of enlightened progressive administration and global superpowerdom. Obviously there are people, right and left, who would prefer that one or both of those projects be abandoned. But they aren’t likely to be running the renamed school. Instead, it will continue to be run by 21st-century Wilsonians — who will now act as if their worldview sprang from nowhere, that its progenitor did not exist, effectively repudiating their benefactor while accepting his inheritance.

Like Nike’s turning Colin Kaepernick into an emblem of social justice while also turning a profit, so Princeton maintains its standing among the nation’s elite institutions, in a Vanna White way, by changing a few letters.

That’s systemic.