John Fea responds to my post that wondered about his ongoing criticism of David Barton, Donald Trump, and the evangelicals who support the POTUS. As convenient as social media is (are?) for carrying on discussions, this one may be bordering on excess.

The nub of the disagreement seems to be the degree to which Christianity should inform judgments about secular politics (I sure hope John agrees that the U.S. is a secular government — it sure isn’t Throne and Altar Christendom). But even behind this question is one about Christianity itself. What kind of religion is Christianity and what are its political aspects?

John’s own religious convictions seem to veer. In one case, he objects to my raising the question of virtue signaling, that by opposing the “right” kinds of bad things, he shows he is not that “kind” of evangelical.

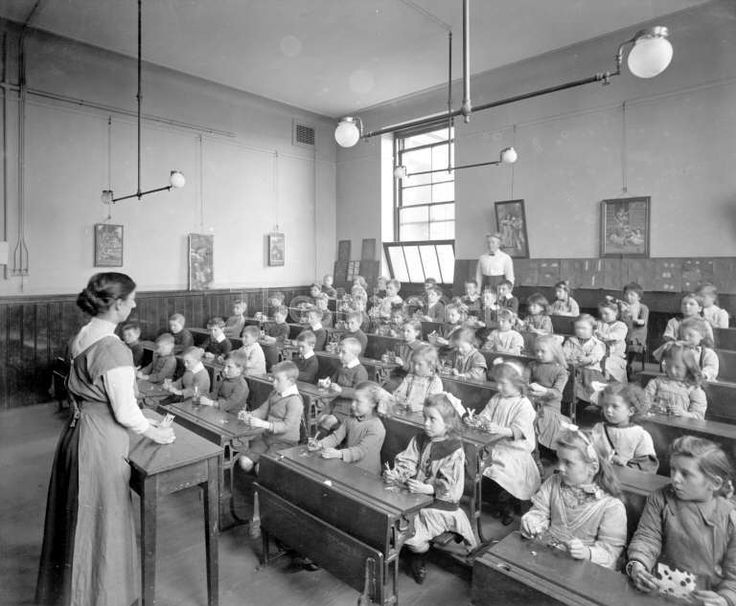

Hart implies that my convictions are not really convictions, but a clever ploy to show people that I am “not that kind of evangelical.” I will try not to be offended. And yes, Hart is correct. Indeed, some of my evangelical readers do understand the difference between Messiah College and Liberty University or David Barton U. I also think that many of my non-evangelical readers and non-Christian readers who may not have understood the difference between these schools have learned from reading The Way of Improvement Leads Home that the world of evangelical higher education is more diverse than they originally assumed. But I also get new readers every day. If my experience is any indication, many folks out there still don’t understand the difference between Messiah College and Liberty University or David Barton University. I hope my blog will teach people that evangelicals are not all the same when it comes to their approach to higher education or politics.

If John has to try not to be offended, I must have offended. My bad. But don’t Christians generally worry about posturing, pride, self-righteousness? Not much these days. And that could be a problem with a certain kind of Christianity, no matter how right in its public interventions, that comes across and being more moral than others. Jesus warned about public piety in the Sermon on the Mount. As a self-acknowledged Christian, should not John be thankful for someone who warns him about the dangers of moral preening?

But John retaliates kind of by locating me in the religious backwaters of Reformed Protestantism:

I should also add that The Way of Improvement Leads Home is not a Reformed Christian blog, a paleo-conservative blog, or a denominational (Orthodox Presbyterian Church) blog. In this sense, it is different than Old Life.

He is broad while Old Life is narrow. But then, even though I am narrowly Reformed (agreed), he faults me also for being secular.

I realize that the kind of approach to government I am espousing here is different from the kind of secularism Hart has written about in his book A Secular Faith: Christianity Favors the Separation of Church and State. According to one synopsis of the book, Hart believes that “the only role of government is to ensure that the laws do not injure faith and its practices.” (This, I might add, is the same kind of thinking put forth by court evangelicals such as Robert Jeffress).

In the end, I think Hart’s warning about mixing church and state is important. You should read A Secular Faith. I read it, enjoyed it, and learned much from it. I also agreed with much of it. I just don’t go as far as Hart in my secularism. This apparently makes me a Christian nationalist.

John does not try to make sense of being narrowly Reformed in church life and broadly secular in politics. His Christianity simply faults me for either being too narrow on religion or too secular on politics. This makes me wonder if John has thought much about two-kingdom theology, whether from Lutheran, Reformed, or Roman Catholic sources. If he had 2k in his tool kit, he might understand that his own evangelical approach to national politics very much follows the play book of neo-evangelical leaders from the 1940s, who followed the national politics (though with revivals thrown in) of the mainline churches. In both cases, ecumenicity, not being narrow in religion, was a way to build coalitions across denominations that would preserve or build (depending on the timing) a Christian America. Now of course, America is a good thing. But to look at the church or Christianity through the lens of its capacity to help the nation is one more instance of immanentizing the eschaton. In other words, you make Christianity (a global faith) narrow on nationalist grounds.

By the way, John’s quote of the synopsis of A Secular Faith — “the only role of government is to ensure that the laws do not injure faith and its practices” — is actually off. The summary of the book from Booklist included this: “That is Augustine’s distinction of the holy city of God from the secular city of man. Christians are perforce citizens of both, but their only specifically Christian obligation concerning secular citizenship is to ensure that the laws do not injure faith and its practices.” John’s quote of the synopsis does allow him to link me to Jeffress. But again, if he knew 2k, he’d be scratching his head over that comparison. Still this tie typifies the way many evangelicals read 2k: if you aren’t with them, you’re on the fringes, either sectarian or secular.

When John moves beyond tit-for-tat, he explains his understanding of government and Christianity’s place in America:

I believe that government has a responsibility to promote the common good. It should, among other things, protect the dignity of human life, encourage families, promote justice, care for the poor, and protect its citizens and their human rights. I also believe in something akin to the Catholic view of subsidiarity. This means that many of these moral responsibilities are best handled locally. This is why I am very sympathetic to “place”-based thinking and find the arguments put forth by James Davison Hunter in his book To Change the World to be compelling.

But when morality fails at the local level, such moral failures must be dealt with by higher governmental authorities. For example, I believe that the intervention of the federal government in the integration of schools during the era of the Civil Rights Movement was absolutely necessary. Local governments and white churches in the South failed on this front. Moral intervention was necessary. I use the term “sin” to explain understand what was going on in these racist Southern communities. Others may not use such theological language and prefer to call it “unAmerican” or simply “immoral.” But whatever we call it, I think we can still agree on the fact that what was happening in the Jim Crow South was morally problematic and the federal government needed to act. I hope Hart feels the same way. If he does, I wonder what set of ideas informs his views on this.

Here John identifies Christianity with morality. Not good. Christianity does point out sin through the moral law. But Christianity actually provides a remedy. Without the remedy, Jesus and the atonement, the moral law is just one big pain in the neck (for the lost, at least). A policy that enacts something that seems like Christian morality is not itself Christian without also including the gospel. This may be the biggest disagreement between John and me. He is willing apparently to regard mere morality as Christian. That means taking to the lost all the imperatives to be righteous without any way to do so. Christian morality, without the gospel, scares the bejeebers out of me (and I don’t think I’m lost), which is another reason for being wary of seeming self-righteous. Who can stand in that great day by appealing to Christian morality? What good is Christianity for America if it doesn’t lead to faith in Christ?

Another larger problem goes with looking to Christianity for moral authority or certainty. This is an old theme at Old Life, but how do you follow the second table of the Ten Commandments — many of which encourage the policies that John thinks government should pursue — without also taking into account those about idolatry, blasphemy, and keeping the Lord’s Day holy. I don’t see how you set yourself up as a follower of Christ while disregarding some of your Lord’s directives?

The kicker is that John admits he could support a president quoting Muslim sources to uphold American ideas:

I think much of what Obama celebrates in Pope Francis’s ideas is compatible with American values. If Obama quoted a Muslim thinker who spoke in a way compatible with American values I would say the same thing.

So is America the norm? Is it Christianity? Or is it John Fea’s moral compass?

John concludes by admitting:

I am opposed to Trump for both Christian and non-Christian reasons and sometimes those reasons converge.

I appreciate the candor but I wonder why John doesn’t see that he here identifies with every other evangelical — from Barton to Jeffress — who merge their political and religions convictions to support a specific political candidate or to argue for their favorite era of U.S. history. Because John converges them in a superior way to Barton and Jeffress, is that what makes his views on politics more Christian, more scholarly, more American?

John is willing to live with the label of Christian nationalist if it preserves him from the greater error of secularism. What I think he should consider is that converging religion and politics is how we got Barton and Jeffress. If John wants to stop that kind of Christian nationalism, he should preferably embrace two-kingdom theology. If not that, at least explain why his version of convergence is better than the court evangelicals, or why he is a better Christian.