John Fea is upset with Jerry Falwell the younger for adopting a 2k position to defend his support for Donald Trump. Here is what Falwell said:

It’s such a distortion of the teachings of Jesus to say that what he taught us to do personally — to love our neighbors as ourselves, help the poor — can somehow be imputed on a nation. Jesus never told Caesar how to run Rome. He went out of his way to say that’s the earthly kingdom, I’m about the heavenly kingdom and I’m here to teach you how to treat others, how to help others, but when it comes to serving your country, you render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s. It’s a distortion of the teaching of Christ to say Jesus taught love and forgiveness and therefore the United States as a nation should be loving and forgiving, and just hand over everything we have to every other part of the world. That’s not what Jesus taught. You almost have to believe that this is a theocracy to think that way, to think that public policy should be dictated by the teachings of Jesus.

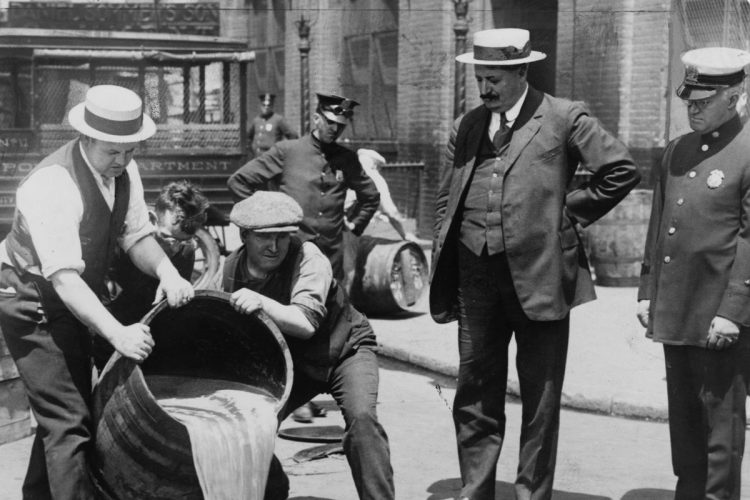

I am not sure I trust Mr. Falwell to capture all the intricacies of 2k political theology, but his rendering here seems quite sensible. You can have a theocracy of the Old Testament or a theocracy of the Sermon on the Mount. Modern sentimentality inclines more people to favor implementing New Testament laws than Israel’s political and civil codes (ouch!). But either way, if you require the government and rulers to conform to the Bible, you are a theonomist. Mind you, conducting war’s in God’s name or abolishing the sale of alcohol are not items you want on your resume if you are a government-should-conform-to-Christianity advocate, which John Fea is every time he uses the Bible, not the Constitution, against Trump.

So why is Falwell’s view dangerous? Fea explains:

Luther’s Two Kingdom belief, as I understand it, is more nuanced and complex than what Falwell Jr. makes it out to be. (I am happy to be corrected here by Lutheran theologians). In fact, I don’t think Luther would have recognized Falwell Jr.’s political theology.

That really doesn’t explain why Falwell is dangerous.

Turn’s out, what’s dangerous is a 2k person who won’t condemn Trump and that’s why John looks for help from a Lutheran who explains that 2k allows you fret about presidents like Trump:

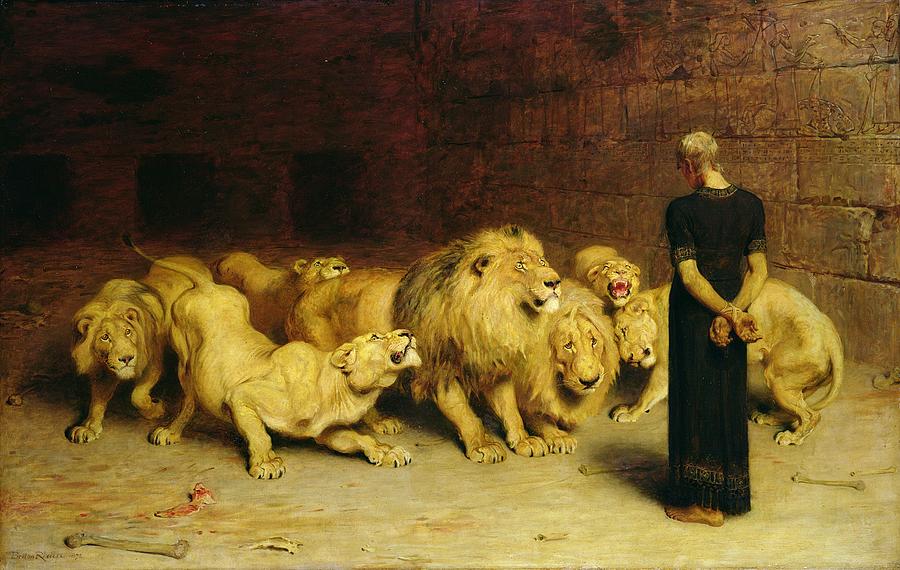

Lutherans must avoid the mistake of the Reformation leaders who failed to cry out against the sins of monarchs. We must exhort all “sword-bearers,” that is, all agents of the state and public servants, from schoolteachers to the president, to live up to the demands of their vocations. Our Lutheran forefathers failed in this task; all the more reason Lutherans today must not.

Conservatives who fear that President Trump may be more like the decadent Belshazzar, feasting while the kingdom falls, than like the liberating Cyrus must pray that Lutherans remember the Two Kingdoms Doctrine. How we discharge the duties of citizenship—whether by accepting the creeping authoritarianism of the last two decades, or by raising our voices on behalf of the laws and democratic norms of our country—is a question of moral conscience, suitable for confession, and demanding repentance if we err.

Even if Lutherans call down God’s wrath on Trump, though, it’s still a judgment call, a question of moral conscience. It does not permit the kind of condemnation that John cites approvingly from Ruth Graham:

At one point, reporter Joe Heim asked Falwell whether there is anything Trump could do that would endanger his support from Falwell and other evangelical leaders. He answered, simply, “No.” His explanation was a textbook piece of circular reasoning: Trump wants what’s best for the country, therefore anything he does is good for the country. There’s something almost sad about seeing this kind of idolatry articulated so clearly. In a kind of backhanded insult to his supporters, Trump himself once said that he could “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody” without losing his base. It’s rare to see a prominent supporter essentially admit that this was true.

A reporter for a secular magazine used the I-word? Idolatry? Why that’s a biblical idea, even in the Old Testament, the same portion of Scripture that calls for the execution idolaters.

Why John Fea doesn’t find the use of that word dangerous, I do not know (though again Trump explains a lot). Falwell’s point is that we should not expect the United States to conform to the rules for church members. Among the errors that churches try to avoid (I wish they did it more) are idolatry and blasphemy. But in the United States, thanks to political liberalism, errors like blasphemy and idolatry have rights, or people who worship false gods receive protection from the government to do so.

Once upon a time, Americans thought dangerous governments that required one form of worship and denied rights to people of other faiths. To see Falwell, son of a man who regularly blurred the kingdoms, recognize that the church has different norms from the state is not dangerous but a breakthrough.