The overture to the PCA General Assembly on racism continues to intrigue if only because this is conceivably a problem just as much for the OPC as for our sister denomination. After all, J. Gresham Machen was no integrationist but held a view of blacks (typical at the time) that anyone today would consider not simply micro but macroracist. So I wonder if the PCA adopts the following overture, will it also petition the OPC to repent for Machen’s sins (for starters):

Therefore be it resolved, that the 44th General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in America does recognize, confess, condemn and repent of corporate and historical sins, including those committed during the Civil Rights era, and continuing racial sins of ourselves and our fathers such as the segregation of worshipers by race; the exclusion of persons from Church membership on the basis of race; the exclusion of churches, or elders, from membership in the Presbyteries on the basis of race; the teaching that the Bible sanctions racial segregation and discourages inter-racial marriage; the participation in and defense of white supremacist organizations; and the failure to live out the gospel imperative that “love does no wrong to a neighbor” (Romans 13:10) . . .

One of the arguments made in defense of overtures like this one is that as the continuation of the Presbyterian Church US, the PCA is institutionally in continuity with the views on race that afflicted its southern Presbyterian forebears:

why should we confess for the sins of a church that we were not a part of? Frankly, I do not really understand this objection. The PCA is a continuing denomination; we claim to continue the PCUS. We must publicly confess and repent for sins of those whom we share a covenantal relationship with. God holds our covenant community responsible for our actions, even our sins, collectively. That’s how God works. We must confess for our failures as a church during the Civil Rights Movement and wherever we’ve sinned.

If you peel back the onion layers of institutional/covenantal ties, where do you stop? Why for instance do the overtures not include slavery since the PCUS and the PCUSA both had church members that owned slaves?

In fact, when it comes to institutional continuity, one could argue that PCA is good since the PCUS adopted measures to condemn segregation and approve integration. In his book on the origins of the PCA, Sean Lucas observes:

In 1954, the PCUS General Assembly adopted a report that affirmed “that enforced segregation of the races is discrimination which is out of harmony with Christian theology and ethics” and that urged southern Presbyterian colleges, campgrounds, and churches to be open to all, regardless of race. (For A Continuing Church, 121)

Of course, resolutions like this prompted conservatives in the PCUS who also eventually led in forming the PCA, to oppose the centralization of church power and ecumenism. Some of the opposition also came from sessions and presbyteries. But as for institutional succession, PCA officers could regard themselves as standing in line with the PCUS’s disapproval of racism and segregation.

In fact, throughout Sean Lucas’ five-part series on race and the roots of the PCA, the overwhelming examples of questionable views about race come not from the institutional church but from persons or periodicals. Here is how Lucas describes G. Aiken Taylor:

He told Nelson Bell, “I don’t like agitation on the social question from either side. I am not an integrationist, neither am I a segregationist. My position on this issue is that a view point of whatever kind should not be made the criterion for determining the place or the worth of a man…or a church paper.” In reply, Bell assured him that there was a range of opinions on segregation among the board of directors for the magazine and that he would not be required to hold to a particular party line. That said, the older man also counseled him not to push his more moderate racial views either: “I feel you would be utterly foolish to come to the Journal as editor and make race an issue–certainly at this juncture. There are so many more important things which need to be faced.” As it would happen, Taylor’s position on race, as evidenced in his writing and editorial practice, would largely harmonize with Bell’s own racial views: downplaying forced segregation, dismayed by outside agitators who stirred up the racial issue, and concerned not to let racial politics divert attention from the largely doctrinal and social issues of the day.

Sometimes presbyteries might weigh in but in one case the condemnation concerned rioting not integration:

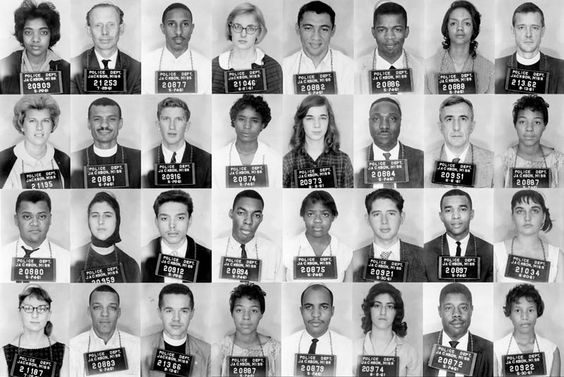

In 1961, East Alabama Presbytery declared itself against the mob violence that engulfed the Freedom Riders in Birmingham and Montgomery: “We express our deep regret and emphatic disapproval of mob violence for whatever cause.”

Even then, only four years later the PCUS took action that would seem to give its Presbyterian successor cover from charges of racism:

When the 1965 PCUS General Assembly endorsed a range of Civil Rights activities, including peaceful demonstrations and sit-ins, over sixty commissioners filed a dissent. Nelson Bell presented it to the assembly, arguing that “some of the methods sanctioned in the document are ‘contrary to or go beyond the jurisdiction of the Church.'” Even if the church desired to support “worthy goals” like racial justice, Aiken Taylor noted, that did not mean that it could do so through “radical measures” or “extremism or vindictiveness.” Later in 1965, Bell worried again that peaceful demonstrations were a small step from civil disobedience and “the step from civil disobedience to riots and violence is even shorter.” Willfully breaking laws, even for a worthy goal, is wrong: “No nation should permit injustice and discrimination to be a part of its accepted way of life. But no nation can survive which placidly allows people to make of themselves prosecutors, jurors, and executioners–and this applies to all citizens.” Means do not justify the end: breaking the law, whether to support segregation or integration, was never right.

Yet, interesting to see is that opposition to General Assembly resolve was not premised on race but on the value of civil disobedience. Yet, when church bodies did engage in explicit forms of racial bigotry, the response of the PCUS and many conservatives (who went into the PCA) was to object:

Second Presbyterian Church, Memphis, Tennessee, drew national attention for its refusal to admit mixed-race groups to corporate worship services. One of several Memphis churches targeted in early 1964 by the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for its “kneel-ins,” Second Church reacted the most negatively. The groups were refused admittance and church officers patrolled the narthex and the front of the church looking for those who would seek to “integrate” the services. The Second Church kneel-ins drew media attention not only because of their racial component, but also because the congregation was scheduled to host the PCUS General Assembly in 1965. As a result, several presbyteries and synods, along with the liberal Presbyterian Outlook, protested allowing the Memphis church to host the assembly; by February 1965, the assembly’s moderator, Felix Gear, a former pastor of Second Church, made the decision to move the coming meeting to the denomination’s assembly grounds in Montreat.

Lucas’ conclusion may be correct that the founding fathers of the PCA sinned, though his book and series show a lot more complications than simply the yes-no question of white supremacy (or not). But the theological question of institutional responsibility for personal sins is a theological question begged rather than answered. Lucas invokes the example of Daniel confessing Israel’s sins:

But his confession is strange–because he doesn’t confess his own private sins, but the sins of Israel and Judah that led to the judgment of the exile: “We have sinned and done wrong and acted wickedly and rebelled, turning aside from your commandments and rules. We have not listed to your servants the prophets, who spoke in you r name to our kings, our princes, and our fathers, and to all the people of the land. To you, O Lord, belongs righteousness, but us open shame” (Dan 9:5-7).

This wasn’t simply lip synching or going through the motions. Rather, Daniel recognized his own covenantal complicity in what his fathers and forefathers had done and in bringing about the exile. And he confessed those sins and repented: “We have sinned, we have done wickedly” (Dan 9:15).

By that same exegesis, isn’t the PCA righteous for the way its parent body, the PCUS, condemned racism and segregation?