Of course, not. The paleo-conservative died in 2005. But what about Bill Ayers (the co-founder of the Weatherman) fundraiser for President Obama?

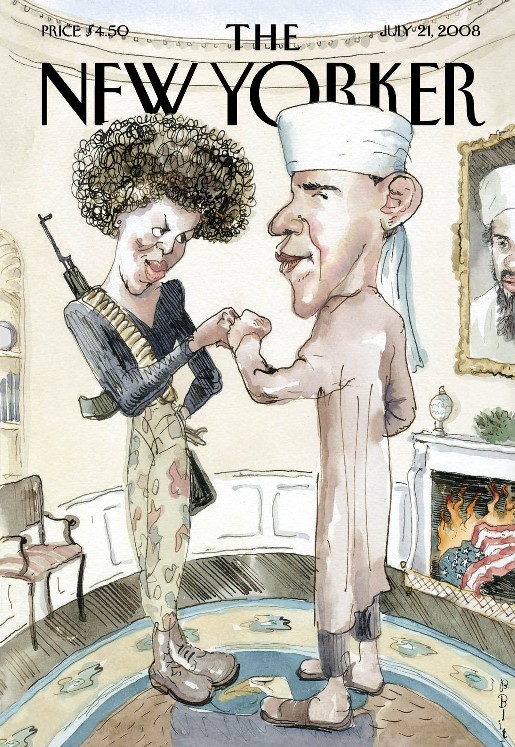

The reason for asking is elite journalism’s tic of recognizing the tawdry associations of president-elect Trump while never having taken seriously President Obama’s associations with the radical left. For instance, I read this in the New Yorker:

Throughout the campaign, he was accused of being the leader of a white backlash movement, waging war on minorities: he says that he wants to expel millions of unauthorized immigrants, and calls for a moratorium on Muslims entering the country. Since his election, many analyses of his political program have focussed on his ties to the alt-right, a nebulous and evolving constellation of dissidents who sharply disagree with many of the conservative movement’s widely accepted tenets—including, often, its avowed commitment to racial equality. This connection runs through Stephen Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist, an “economic nationalist” who was previously the executive chairman of Breitbart, a news site that aimed to be, Bannon once said, “the platform for the alt-right.” Earlier this year, Breitbart published a taxonomy of the alt-right that included Richard Spencer, a self-described “identitarian” whose political dream is “a homeland for all white people.” At a recent conference in Washington, Spencer acted out the worst fears of many Trump critics when he cried, “Hail Trump! Hail our people! Hail victory!” Later, Spencer told Haaretz that the election of Trump was “the first step for identity politics for white people in the United States.”

It is important to note that the link between Trump and someone like Spencer is tenuous and seemingly unidirectional. (When reporters from the Times asked Trump about the alt-right, in November, he said, “I disavow the group.”) But it is also true that partisan politics in America are stubbornly segregated: exit polls suggest that about eighty-seven per cent of Trump’s voters were white, which is roughly the same as the corresponding figure for his Republican predecessor, Mitt Romney. It is no surprise that many of Trump’s critics, and some of his supporters, heard his tributes to a bygone American greatness as a form of “identity politics,” designed to remind white people of all the power and prestige they had lost.

It is true, too, that Trumpism draws on a political tradition that has often been linked to white identity politics. One Journal author suggested that the true progenitor of Trumpism was Samuel Francis, a so-called paleoconservative who thought that America needed a President who would stand up to the “globalization of the American economy.” In Francis’s view, that candidate was Pat Buchanan, a former longtime White House aide who ran for President in 1992 and 1996 as a fiery populist Republican—and in 2000 as the Reform Party candidate, having staved off a brief challenge, in the primary, from Trump.

Three graphs of a long story on Trump and the alt-right even though the reporter also concedes, “what is striking about Trump is how little he engages, at least explicitly, with questions of culture and identity.” “[A]t least explicitly” gives the reporter room to disbelieve Trump and to leave readers inclined to think the worst thinking the worst.

So doesn’t that make the New Yorker the alt-left equivalent of Breitbart?

The question is how to parse these associations and affinities. Do you rely on hard evidence? Do you define narrowly the overlap between the politician and the offensive action or idea? Consider how Noam Scheiber cleared President Obama of untoward associations with Ayers:

Suppose we were talking about a meeting Mike Huckabee attended during a (fictitious) run for state senate in the early ’90s. Let’s say the meeting took place in the home of a local pastor, who, back in the ’70s, had been part of a radical anti-abortion group that at times attempted, but never succeeded in, bombing abortion clinics. The pastor was never prosecuted and had since become a semi-respectable member of his community, where he also ran an adoption clinic for children of mothers he’d counseled against abortion.

If Huckabee had once addressed a group of local conservative activists at the pastor’s home, would that tell us anything about his views on political violence? Reasonable people can disagree about this. But I don’t think it would.

But that is not the standard that Kalefa Sanneh of the New Yorker is using for Trump or the alt-right. Although he has no clear links between Spencer and Trump, because people who like Spencer voted for Trump — kahbamb — association confirmed. But because Bill Ayers and former supporters of the radical left (even in its terrorist phase) voted for Obama, no connection. Just the way the system works.

Which is true. Bad people vote for good candidates all the time. We wonder why such candidates appeal to such voters. But to see the New Yorker do what Rush Limbaugh does is well nigh remarkable. Rush assumes that people who vote Democrat are overwhelmingly bad citizens or bad Americans. Turns out — thanks to the revelations that have arisen during Trump’s candidacy and election — that editors of “respectable” journalism do the same. If you voted for Trump you must be harboring views of white supremacy. Just because you think immigration and ISIS may be a problem?