The subject of confessionalism in relation to the Gospel Coalition has again come up, this time with a charitable defense of the organization from Ligon Duncan. The article that elicited this response is not at issue here. I have not read it nor is that as pertinent as what Duncan says about confessionalism:

None of us are a part of TGC because we don’t care about our ministerial vows or because we don’t really believe our Confession.

We are a part of TGC because TGC beautifully promotes certain important things in the wider Christian and evangelical world that are needed, vital, true, good, right, timely, healthful, and which are also perfectly consistent with our own confessional theological commitments, so we want to be a part and a help. We also think that we have a thing or two to learn from our non-Presbyterian friends in TGC that “sweetly comport” with our vows and our church’s doctrine and practice. And we love the friendship and fellowship we enjoy with like-minded brethren from and ministering in settings denominationally different from our own, but committed to the same big things.

Just as Charles Hodge of Princeton (not one shy of his confessional Presbyterian commitments), for similar reasons, was happy to participate in the Evangelical Alliance in the nineteenth century, so also I am happy to participate in TGC.

This is an important historical matter that deserves more attention. What was the relationship of Hodge’s Old School Presbyterianism to interdenominational endeavors like the Evangelical Alliance? And how did Hodge’s own opposition to the 1869 reunion of the Old and New School churches relate to endeavors like the Evangelical Alliance?

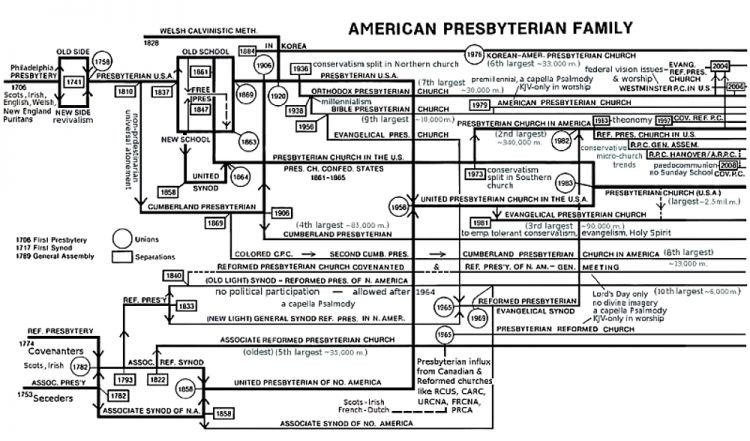

One way of answering that question is to notice that the sorts of cooperation in which mainline Protestants engaged after the Civil War, with the 1869 Presbyterian reunion paving the way, fueled ecumenical and social gospel endeavors that produced conservative opposition in the 1920s and 1930s. The Evangelical Alliance was the Moral Majority of its day, wanting immigrants to conform to Protestant norms, opposed to Romanism and communism (for starters), and it provided the vehicle for Protestants to unite to defend a Christian America. Those ecumenical impulses eventually produced the Federal Council of Churches in 1908 and the Plan for Organic Union in 1920, a proposal that would have united all mainline Protestants into one national church — the way Canadian Protestants at roughly the same time formed the United Church of Canada (1925).

What the period of interdenominational cooperation meant for Presbyterians was a 1903 revision of the Confession of Faith. That revision enabled the PCUSA to receive the Cumberland Presbyterians. Revision softened the Confession’s Calvinism to make room for a body that had left the church almost one hundred years earlier over objections to election and limited atonement. Presbyterians going along for the ecumenical ride included the president of Princeton Theological Seminary, J. Ross Stevenson, who presented the Plan for Organic Union to the 1920 General Assembly. J. Gresham Machen was a first-time commissioner to that Assembly and Princeton’s faculty’s opposition to that plan was start of a denomination wide controversy that forced the 1929 reorganization of Princeton Seminary (to make it tolerant of diversity) and the simultaneous founding of Westminster Seminary.

According to Lefferts Loetscher, who wrote a book with a title that frightened conservatives in the PCUSA and the PCUS, The Broadening Church (1954), the reunion of Old and New School in 1869 touched off developments that saw the PCUSA recover its historic breadth:

Once again in 1869, as in 1758, the Presbyterian Church was restoring unity not by resolving its differences, but by ignoring and absorbing them. Men who had been denounced as “heretics” in 1837 and who had professed no change of theological viewpoint in the interim were welcomed in 1869 as honored brethren. The result was, of course, that the theological base of the Church (especially of the former Old School branch of the Church) was broadened and the meaning of its subscription formula further relaxed. The gentlemen’s agreement of 1869 to tolerate divergent types of Calvinism meant that clear-cut definitions of Calvinism would not be enforceable in the reunited Church, and that it would be increasingly difficult to protect historic Calvinism against variations that might undermine its essential character. (8)

No one actually doubts whether the Old and New Schools were liberal. By almost every measure, both sides would come out as evangelical today (especially if you don’t apply the category of confessionalism). And yet, the breadth necessary for combining both sides also made room for a range of theological ideas that spawned liberalism.

In other words, breadth is not a good thing. Broadening churches are usually ones that become liberal.

So why is an organization that tolerates a diversity of “evangelical” convictions going to avoid that problems that usually surface when you recognize you need to be broader than your own communion is? The answer is not that the Gospel Coalition is going liberal. But an objection to the Gospel Coalition is that it does not have built in transparent mechanisms for identifying and disciplining liberalism.

And here are a couple ways that the Coalition’s breadth could collide with my own Presbyterian confessionalism. If I am a member of the Council and an officer in a confessional Presbyterian church, and my communion has a controversy over someone ordained who does not affirm the doctrine of limited atonement, will I receive support for my opposition to this erroneous officer from my friends and colleagues at TGC? Or what about the Federal Vision? If my church decides that Federal Vision is a dangerous set of teachings that need to be opposed, will my friends and colleagues at TGC support my church in its decision? Will people who write for Gospel Coalition even be clear about the covenant theology that is clearly taught in the Confession of Faith? Or will some of them think that my communion is too narrow in its understanding of Reformed Protestantism? Will they think that the proper response should be one to include a breadth of views in denominations because that is the norm for the Coalition? I could well imagine feeling some pressure to weigh matters before a presbytery or Assembly with my peers in the Coalition in mind? Will I disappoint them? Maybe that’s the wrong way of asking the question. What if they don’t care about the affairs of my communion the way I do? (Why should they care since they are not members or officers of my denomination?)

These are real dilemmas for anyone who has subscribed the Confession and Catechisms and been ordained in a Presbyterian communion while also belonging to an evangelical organization with standards different from the church. They are concerns that have been around for almost 160 years. The Gospel Coalition has not brought an end to church history.