This is a follow up and updates this in the light of even more chatter.

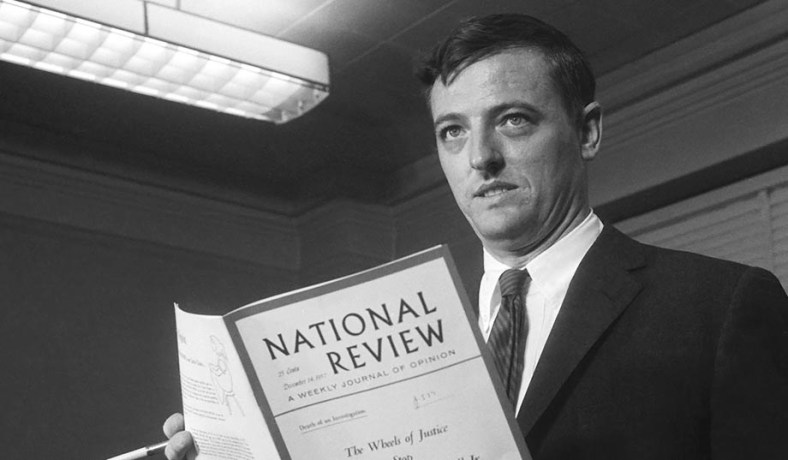

Sohrab’s Ahmari’s critique of French-ism, the outlook of the evangelical attorney and Iraq War veteran, David French (not to be confused with Moby), who writes for National Review was over the top. But it did capture a problem in French’s above-it-all-I-just-follow-the-Declaration-and-Constitution self-fashioning. That is one of putting convictions into practice and forming institutions to maintain them.

French says his outlook consists of:

“Frenchism” (is that a thing now?) contains two main components: zealous defense of the classical-liberal order (with a special emphasis on civil liberties) and zealous advocacy of fundamentally Christian and Burkean conservative principles. It’s not one or the other. It’s both. It’s the formulation that renders the government primarily responsible for safeguarding liberty, and the people primarily responsible for exercising that liberty for virtuous purposes. As John Adams said, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

The problem is, as William F. Buckley saw when he founded National Review, that holding up the ideals of classical liberalism requires taking sides. You nominate candidates, vote in elections, and decide on laws and policy. You may believe in the Bible, by analogy, but you need to interpret it, write a creed, institute a polity, and decide who may be ordained to ecclesiastical office. Simply saying that you believe in the founding or in the Bible without taking a side politically or denominationally is to fly in a hot air balloon above the fray — except that you’re receiving a pay check from either a magazine that has for over fifty years been taking the movement conservative side of interpreting the founding or a denomination that has identified for forty years with a American conservative Presbyterian rendering of the Bible.

Both French and Keller don’t want to be partisan or extreme which is why they reach for the high-minded origins of either the U.S. or Christianity. They don’t want to fight alongside others. They may employ their own arguments either in court or as a public theologian but having the backs of others in a particular group is not the way they seem to carry it.

No Machen’s Warrior Children here.

This is why Rod Dreher sees Ahmari’s point, namely, that French positions himself above the clamor of division or controversy:

I concede that I’m more of a classical liberal than I thought I was, in that I resist a coercive political order. I am willing to tolerate certain things that I think of as morally harmful, for the greater good of maintaining liberty. Not all sins should be against the law. Again, though, there’s no clear way to know where and how to draw the line. Sohrab Ahmari uses Drag Queen Story Hour as a condensed symbol of the degrading things that contemporary liberalism forces on the public.

I am a thousand percent behind Ahmari in despising this stuff, and I am constantly mystified by how supine most American Christians are in the face of the aggressiveness of the LGBT movement and its allies, especially in Woke Capitalism. I am also a thousand percent with Ahmari in his general critique of how establishment conservatism tends to capitulate to cultural liberalism.

But French has the virtue of being virtuous, which is why Alan Jacobs sees the National Review correspondent as merely being a good Christian:

I disagree with David French about a lot of things — especially what I believe to be his sometimes uncritical support for American military action — but I admire him because he’s trying. He’s trying to “take every thought captive to Christ.” I believe that if you could demonstrate to David French that positions he holds are inconsistent with the Christian Gospel, he would change those positions accordingly. Among Christians invested in the political arena, that kind of integrity is dismayingly rare.

Hey, Dr. Jacobs! I try too. But the day I see you come alongside confessional Presbyterians and say, “they are simply trying to live out the Christian gospel” I’ll book a flight to Waco and buy you a drink.

But Jacob’s reaction is precisely the problem. To regard French’s politics as simply trying to be consistent with Christianity — aside from being a violation of two-kingdom theology — is to ignore that politics requires getting dirty and making compromises. It is not a place to pursue holiness and righteousness — though it is an occupation worthy of a vocation.

So, while David French takes his stand with Burke, Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Jesus (as if those add up to anything coherent), French-ism is nowhere in Matthew Continetti’s breakdown of contemporary conservatism — trigger warning for #woke and Neo-Calvinist Christians who want their politics to come from either the prophets or the apostles:

The Jacksonians, Mead said, are individualist, suspicious of federal power, distrustful of foreign entanglement, opposed to taxation but supportive of government spending on the middle class, devoted to the Second Amendment, desire recognition, valorize military service, and believe in the hero who shapes his own destiny. Jacksonians are anti-monopolistic. They oppose special privileges and offices. “There are no necessary evils in government,” Jackson wrote in his veto message in 1832. “Its evils exist only in its abuses.”

…Reform conservatism began toward the end of George W. Bush’s presidency, with the publication of Yuval Levin’s “Putting Parents First” in The Weekly Standard in 2006 and of Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam’s Grand New Party in 2008. In 2009, Levin founded National Affairs, a quarterly devoted to serious examinations of public policy and political philosophy. Its aim is to nudge the Republican Party to adapt to changing social and economic conditions.

…Where the paleoconservatives distinguish themselves from the other camps is foreign policy. The paleos are noninterventionists who, all things being equal, would prefer that America radically reduce her overseas commitments. Though it’s probably not how he’d describe himself, the foremost paleo is Tucker Carlson, who offers a mix of traditional social values, suspicion of globalization, and noninterventionism every weekday on cable television.

…The Trump era has coincided with the formation of a coterie of writers who say that liberal modernity has become (or perhaps always was) inimical to human flourishing. One way to tell if you are reading a post-liberal is to see what they say about John Locke. If Locke is treated as an important and positive influence on the American founding, then you are dealing with just another American conservative. If Locke is identified as the font of the trans movement and same-sex marriage, then you may have encountered a post-liberal.

The post-liberals say that freedom has become a destructive end-in-itself. Economic freedom has brought about a global system of trade and finance that has outsourced jobs, shifted resources to the metropolitan coasts, and obscured its self-seeking under the veneer of social justice. Personal freedom has ended up in the mainstreaming of pornography, alcohol, drug, and gambling addiction, abortion, single-parent families, and the repression of orthodox religious practice and conscience.

For those keeping score at home, that’s Jacksonians, Reformocons, Paleocons, and Post-Liberal conservatives. None of them are “classical liberals.” History moves on and requires people to choose.